Abstract

Objective The purpose of this study was to determine the effect that two guides to tooth preparation had on an operator's ability to appropriately and consistently prepare teeth for porcelain laminate veneers.

Study design In-vitro study

Materials and methods Thirty typodont central incisor teeth were randomly allocated into three groups and a general dental practitioner was asked to prepare the teeth for porcelain laminate veneers. Group A were prepared freehand while Groups B and C were prepared with the assistance of a silicone index and depth preparation bur respectively. Images of the prepared teeth were used to calculate the mean labial depth of preparation and incisal reduction of teeth in each group.

Results The mean labial reduction for Groups A, B and C was 0.37 mm (SD 0.13), 0.62 mm (SD 0.17) and 0.61 mm (SD 0.15) and the mean incisal reduction for Groups A, B and C was 1.0 mm (SD 0.28), 1.0 mm (SD 0.38) and 1.03 mm (SD 0.26) respectively.

Conclusion It is suggested that consideration be given to the use of a silicone index or depth gauge bur when teeth are prepared for porcelain laminate veneers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

With the exception of vital bleaching, the most used preservative treatment for unsightly, but otherwise sound, anterior teeth is the provision of porcelain laminate veneers.1 The porcelain laminate veneer restoration, as first described by Horn2 gained widespread acceptance with a survey of 200 practitioners in the US in the late 1980s and early 1990s reporting that practitioners placed a mean of 200 porcelain laminate veneer restorations over a 3-year period.3There is evidence, however, that the numbers of porcelain laminate veneers prescribed in England and Wales is falling, and practitioners would seem to prefer more destructive techniques including full veneer crowns for the management of unattractive anterior teeth.4 It has been suggested that the lack of a predictable outcome with porcelain laminate veneer restorations, invariably as a result of poor tooth preparation, may be responsible for the practitioner's reticence to continue to prescribe them in preference to more extensive forms of restoration.4 Such a trend is cause for concern given that full coverage restorations are less preservative5 of tooth tissue and are associated with an increased incidence of periradicular periodontitis.6

Accepted recommendations, although not evidence based, for preparations for porcelain laminate veneers require the operator to reduce the labial surface uniformly, within enamel, by 0.5 mm.7Inadequate labial reduction can potentially lead to increased bulk in the veneer8 while over reduction needlessly results in more extensive dentine exposure.9 In cases where the operator fails to achieve uniform reduction of the labial surface, taking account of the facial contours of the tooth, it is common to find areas of both inadequate and unnecessarily extensive reduction within the same preparation.4

Initially four types of preparation were described for porcelain laminate veneers; only two of which required the incisal edge to be prepared.10 Currently it is accepted however that when teeth are prepared for porcelain laminate veneers the incisal edge should be reduced by 1.0 mm and finished with a bevel or overlapped onto the palatal surface.11 The requirement to reduce the incisal edge has recently been questioned in two studies, which reported equivalent longevity for porcelain laminate veneers with and without incisal overlap.12,13,13 It is suggested however that until further evidence is forthcoming the incisal edge be reduced when teeth are prepared for porcelain laminate veneers.11 Two studies have reported a tendency for practitioners to under prepare teeth for porcelain laminate veneers with under preparation of the middle incisal third of the tooth being especially common.14,15,15

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect that guides to depth preparation have on an individual practitioner's ability to correctly and consistently prepare teeth for porcelain laminate veneers.

Methods and materials

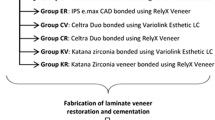

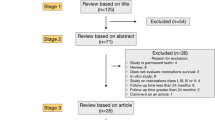

Thirty typodont, upper right incisor, teeth (Riverside Dental Manufacturers, London, UK) were mounted singly in plaster blocks and randomly allocated to three equal groups (A, B and C) using random number tables. A prosthodontist with suitable postgraduate training, attuned to the preparation required for porcelain laminate veneers, was invited to prepare each tooth for a porcelain laminate veneer restoration using standard burs (Burs 0835, 0835F, Shofu Inc, Kyoto, Japan). The practitioner was not told of the purpose of the study until all the preparations had been completed. Group A teeth were prepared freehand, Group B teeth were prepared using a sectioned index (Fig. 1) formed from an addition cured silicone impression material (Provil, Heraeus Kulzer Ltd, UK) and the Group C teeth were prepared using a depth gauge (0.5 mm) bur (S4 bur, Intensiv SA, Lugano, Switzerland) (Fig. 2).

The technique for measuring depth of preparation originally described by Nattress et al.,15 was modified for the purposes of the study. Prior to tooth preparation a sectional index that could be reconstructed over the original tooth was produced using an addition cured silicone impression material. Following tooth preparation the index was reconstructed and a light body addition cured silicone, of contrasting colour, injected into the index to occupy the space created by tooth preparation. The index was then sectioned axially along the midline of the prepared tooth with a scalpel and the left-hand side mounted on a microscope slide.

An optical microscope, with a resolution of ± 0.02 mm, attached to a personal computer was used to capture an image of the sectioned relined index (Fig. 3), which was subsequently analyzed by an image analysis package (HL Image ++, Data Translation Limited, Basingstoke, UK; Sigma Scan, SPSS ASC Erkrath, Germany). Five measurements (Fig. 3) of the labial reduction and one of the incisal reduction were obtained on two occasions. These results were averaged to give a mean labial and incisal reduction for each preparation. The data were analyzed using a one way analysis of variance and Scheffe's post hoc statistical test.

Results

The mean labial reduction for Groups A, B and C was 0.37 mm (SD 0.13), 0.62 mm (SD 0.17) and 0.61 mm (SD 0.15) respectively. The mean incisal reduction for Groups A, B and C was 1.0 mm (SD 0.28), 1.0 mm (SD 0.38) and 1.03 mm (SD 0.26) respectively. There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between the three groups with respect to the labial reduction. In contrast, there was no significant difference (P > 0.05) between the three groups with respect to incisal reduction. The labial reduction for Group A was less than that of Groups B and C, which were similar. Scheffe's test revealed that this difference was significant at the 5% level of significance.

Discussion

The labial reduction for teeth in Group A was accomplished freehand, which it is suggested is typical of clinical practice. The results of this study suggest that teeth prepared in this way for porcelain laminate veneers would tend to be under prepared. This supports the findings of a previous clinical study, which reported that clinicians tend to under prepare the labial aspect of teeth for porcelain laminate veneers,4 which produces overcontouring of the restored tooth.16

Under preparation creates a technical problem when the laminate veneer restoration is produced in the laboratory. To compensate for under preparation the technician often has to over bulk the restoration. It has been shown that excessive bulk in the gingival part of the restoration can adversely effect the emergence profile, which may initiate inflammation of the adjacent gingivae.17 Increased bulk in the incisal part of the restoration produces poor aesthetics but more importantly it can alter the protrusive relationship leading to atypical occlusal loading of the veneer and possible subsequent fracture. Under preparation of severely discoloured teeth especially will also result in a poor aesthetic outcome. A thin layer of porcelain has a limited ability to disguise severely discoloured underlying tooth tissue.18

Teeth prepared with a silicone index or a depth gauge bur (Groups B and C) were slightly over prepared. It is therefore likely that increased amounts of dentine will be exposed within the preparation. This is particularly the case in the cervical third of the preparation where the enamel is very thin.19 This will not compromise the ultimate restoration, provided such dentine exposure is embodied within the preparation and all margins are within enamel. Whenever porcelain laminate veneers are cemented however the use of a dentine-bonding agent and associated resin-based luting system is therefore recommended.15

When a silicone index is used to prepare teeth for porcelain laminate veneers the results of this study suggest that an operator's ability to distinguish comparative depths of preparation is accurate to within 0.1 mm given that the teeth prepared with a silicone index were over prepared by 0.1 mm. The use of a depth gauge bur involves additional smoothing out of the grooves produced by the bur. When this is done it appears that there is a tendency to slightly over prepare the labial surface of the preparation by 0.1 mm. Further research is needed to establish whether the use of a 0.4 mm depth gauge bur would enable practitioners to correctly reduce the labial aspect of a preparation for a porcelain laminate veneer.

It could be considered a limitation of this study that the teeth were prepared in isolation with the sole operator not being able to use abutment teeth to help gauge tooth reduction. It is questionable however whether the presence of abutment teeth would have affected tooth preparation given that practitioners still under prepare teeth for porcelain laminate veneers clinically even when abutment teeth are present.14 Should the adjacent teeth be worn or have atypical morphology not common to the tooth being prepared, using such a tooth as a guide during tooth preparation may well result, for example, in an over prepared tooth if the adjacent tooth has significant non-carious tooth tissue loss.

Given the tendency to under preparation when teeth are prepared freehand, it is recommended that either an index or appropriate depth gauge bur are used when teeth are prepared for porcelain laminate veneers. Some freehand preparation of severely discoloured teeth will still be required so as to ensure a successful aesthetic outcome, an increased thickness of porcelain and/or luting cement in the final restoration having a greater masking ability.20Similarly teeth, which have suffered some degree of non-carious tooth surface loss should be prepared accordingly with a combination of margin definition and selected free hand reduction where appropriate. Blanket preparation with an index or depth gauge bur would not be appropriate in such cases.

The present trend when teeth are prepared for porcelain laminate veneers is to include the incisal edge either by bevelling or by means of overlapping. A silicone index is more helpful than a depth gauge bur when preparing the palatal surface and reducing the incisal edge, a depth gauge bur having limited application in these situations. It could be considered that a disadvantage of making an index of addition cured silicone is the expense in terms of material and time required to produce such an index. It is suggested however that the benefits to the patient and the operator from using a silicone index far exceed the additional cost of fabricating the index. A further advantage of a silicone index is that it can be sectioned so that the parts can be relocated accurately. The index can then be reconstructed and used to fabricate a temporary restoration. If a depth gauge bur is used in preference to a silicone index minimal smoothing of the labial face to prevent over preparation is recommended.

Conclusion

It is concluded that freehand preparation of teeth for porcelain laminate veneers results in under preparation of the labial aspect of the preparation. The use of a silicone index or a depth gauge bur with minimal additional smoothing is recommended to produce appropriate reduction of the labial surface of teeth when preparing teeth for porcelain laminate veneers.

References

Christensen G J Veneering of teeth. State-of-the-art. Dent Clin North Am 1985; 29: 373–391.

Horn H R Porcelain laminate veneers bonded to etched enamel. Dent Clin North Am 1983; 27: 671–684.

Christensen G J Have porcelain laminate veneers arrived. J Am Dent Assoc 1991; 122: 81.

Brunton P A, Wilson N H F Preparations for porcelain laminate veneers in general dental practice. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 553–556.

Anusavice K Materials of the future: Preservative or Restorative. Oper Dent 1998; 23: 162–167.

Saunders W P, Saunders E M Prevalence of periradicular periodontitis associated with crowned teeth in an adult Scottish subpopulation. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 137–140.

Garber D A Rational tooth preparation for porcelain laminate veneers. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1991; 12: 316, 318, 320 and 322.

Pameijer C H Porcelain laminate veneers. J Calif Dent Assoc 1991; 19: 59–62.

Weinberg L A Tooth preparation for porcelain laminates. N Y State Dent J 1989; 55: 25–28.

Clyde J S, Gilmour A Porcelain veneers: A preliminary review. Br Dent J 1988; 164: 9–14.

Calamia J R Materials and techniques for etched porcelain facial veneers. Alpha Omega 1988; 81: 48–51a.

Meijering A C, Creugers N H Roeters F J, Mulder J Survival of three types of veneer restorations in a clinical trial: a 2.5 year interim evaluation. J Dent 1998; 26: 563–568.

Nordbo H, Rygh-Thoresen N and Henaug T Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers without incisal overlapping: 3-year results. J Dent 1994; 22: 342–345.

Brunton P A, Richmond S Wilson N H F Variations in the depth of preparations for porcelain laminate veneers. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 1997; 5: 89–92.

Nattress B R, Youngson C C Patterson C J W, Martin D M, Ralph J P An in vitro assessment of tooth preparations for porcelain veneer restorations. J Dent 1995; 23: 165–170.

Meijering A C, Peters M C R B, DeLong R, Pintado M R, and Creugers N H J Dimensional changes during veneering procedures on discoloured teeth. J Dent 1998; 26: 569–576.

Perel M L Axial Crown Contours. J Prosthet Dent 1971; 25: 642–649.

Barghi N, McAlister E Porcelain for veneers. J Esthetic Dent 1998; 10: 191–197.

Shillingburgh H T, Scottgrace C Thickness of enamel and dentine. J South Calif Dent Assoc 1973; 41: 33–52.

McLaughlin K, Morrison J E Porcelain fused to tooth-The state of the art. Restorative Dent 1988; 4: 90–94.

Acknowledgements

Paul A Brunton was awarded the British Society for Restorative Dentistry Research Prize 1999 for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunton, P., Aminian, A. & Wilson, N. Tooth preparation techniques for porcelain laminate veneers. Br Dent J 189, 260–262 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800739

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800739

This article is cited by

-

Age and sex related change in tooth enamel thickness of maxillary incisors measured by cone beam computed tomography

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Clinical survival of No-prep indirect composite laminate veneers: a 7-year prospective case series study

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Minimal invasive microscopic tooth preparation in esthetic restoration: a specialist consensus

International Journal of Oral Science (2019)

-

Porcelain laminate veneers – what is the best way to prepare the tooth?

British Dental Journal (2000)