Abstract

Objective To describe the variety of arrangements for providing out-of-hours dental care in the UK.

Design A telephone interview survey of health authorities and health boards.

Setting United Kingdom.

Subjects 104 health authority contacts, usually consultants in dental public health, dental advisers or others in a position to describe the local dental service arrangements.

Results At weekends, 25 authorities have no formal dental care arrangements for unregistered patients, 55 have separate arrangements for registered and unregistered patients, and 44 have 'universal access' arrangements — for anyone in an area, regardless of their registration status. On weekday nights over two-thirds (82/124) of UK health authorities have no formal arrangements for unregistered patients. Where there are separate 'safety-net' services intended for unregistered patients only they are usually (in 48 of 55 authorities) emergency treatment sessions. A fifth of authorities reported planned changes to their local out-of-hours arrangements, including the introduction of telephone triage, and moves to make care available at more times, to more people or from centralised premises.

Conclusions There is extremely wide geographical variation in the organisation of out-of-hours dental services provided in the United Kingdom. In many parts of the UK there are no formal out-of-hours care arrangements for unregistered patients, even at weekends. This unequal provision will mean inequitable access for many unregistered patients. With increasing demands from a growing unregistered population, and various government initiatives to make primary care services more integrated and accessible, the highly fragmented pattern of provision in many areas may no longer be acceptable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

At present in the UK, if people suffer dental pain or have another oral health problem at night or at the weekend, whether and how they obtain advice or treatment depends on a complex combination of their location, the availability of local dental services, their knowledge and experience of these services, and whether they are registered with an NHS dentist. Many people seek care from a dentist, possibly their regular dentist if they are registered. In the year 1997/98 there were more than 312,000 recalled attendances in the UK, where dentists re-opened their premises outside normal surgery hours, at a cost of more than £14 million to the NHS.1,2,3 A considerable number seek care out-of-hours at emergency dental clinics, typically run at weekends within community dental service (CDS) or hospital premises.4,5 Others, who perhaps fear dentists or are not aware that dental care may be available out-of-hours contact their medical general practitioner,6 or go to their local accident and emergency (A & E) department.7,8

In many areas this arguably constitutes a costly duplication of services.4 Wide variations in local arrangements might also imply inequity of access. Indeed, the poor accessibility and availability of services outside normal surgery hours has been shown to be one of the main sources of patient dissatisfaction with dental care.9

In general medical practice, national surveys have monitored shifts in out-of-hours service provision.10,11 Deputising services and more recently GP co-operatives have emerged as distinct models of organising out-of-hours care.12 For dental services the situation is less clear. While some local arrangements could be described as 'dentist cooperatives',13 and other ways of organising emergency dental care have been advocated,14,15,16 it is not clear whether there are distinct models of organising emergency dental services. There have been numerous studies of patients attending particular services, but more comprehensive information about how these services are organised has not usually been presented. There is therefore no reliable UK-wide information about out-of-hours dental care provision. This study aimed to describe the main out-of-hours dental services or dental care arrangements throughout the UK, with particular attention to the intended clients of different services.

Method

A telephone survey of all 124 UK health authorities or health boards was carried out between July and November 1998. The investigator (RA) telephoned each authority and asked to speak to 'the consultant in dental public health or another senior dentist attached to the health authority'. This led to a total of 104 telephone interviews with senior dentists attached to the authority or others in a position to describe local service arrangements, such as dental contracting managers or representatives of the local dental committee (LDC).

The interviewees were asked to describe the main out-of-hours dental care arrangements in their area, with particular attention to any separate arrangements intended for registered patients and unregistered patients, or services or rotas aiming to care for all patients regardless of registration status. The interview was deliberately conversational, to encourage participation. However questions were asked about some standard points such as the intended clients (eg registered and/or unregistered patients), the level of service (advice only, advice plus recalled attendance, walk-in treatment sessions etc), the treatment setting, staffing and pay arrangements, and days and hours of availability of the main dentist-provided out-of-hours services in each health authority area.

In practical terms, for each area it was not possible to summarise the varied arrangements made by individual practices or dentists for their registered patients. Information was also not directly sought about any out-of-hours arrangements specifically for CDS patients, nor about the level of service offered by on-call oral and maxillofacial surgeons within A & E departments. Some additional calls were made in 1999 to gather missing information.

Results

Service descriptions were obtained from all 124 health authorities/health boards, with no refusals to provide information. The service descriptions were obtained from 104 telephone interviews, including: 41 with consultants or registrars in dental public health, 30 with dental advisers, 30 with the 'primary care/dental contracts/commissioning manager' and 3 with the local dental committee chair. The latter were sometimes recommended as the most knowledgeable contact regarding out-of-hours dental care arrangements. Some of the contacts held positions in and provided information about more than one health authority.

The semi-structured interviews yielded both 'factual' information — for example the times and treatment settings of services — and more ambiguous or subjective information about what has influenced the development and use of local services. The results presented relate mainly to the factual information reported about the formal out-of-hours service arrangements for unregistered patients. Any information thought to be ambiguous or less reliable is indicated.

To simplify the presentation of the results three types of area have been defined (Fig. 1). At one extreme there were those areas (25 authorities) where there were no formal out-of-hours arrangements for patients not registered with an NHS dentist, even at weekends. In other areas (55 authorities) there were formal arrangements intended to provide out-of-hours dental care for unregistered patients. In the remaining 44 health authorities there were weekend services intended to cater for anyone calling or attending with a dental problem, regardless of their registration status ('universal access' arrangements). During weekday nights there are fewer authorities with formal arrangements for unregistered patients: 42 compared with 99 authorities at weekends. Therefore in over two thirds (82/124) of authorities there are no formal dental care arrangements for unregistered patients on weekday evenings or nights.

In spite of the variety of arrangements at health authority level, there were no stark regional variations, with one or more examples of all three main types of arrangement in virtually all UK health regions. All 11 UK health regions had some authorities with universal access arrangements, and in 10 health regions there was at least one authority without any formal arrangements for unregistered patients at weekends.

Out-of-hours arrangements for unregistered patients

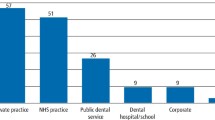

Table 1 shows the level of service, days of service availability, treatment setting and staffing of out-of-hours services for unregistered patients, whether as part of universal access arrangements or when provided as a separate service. Of the health authorities which have separate services for unregistered patients, over four-fifths (45) provide 'walk-in' treatment sessions only. In most (39) of these authorities the sessions are provided only at weekends or public holidays, and are usually provided in NHS premises rather than at a dentist's own practice. In contrast, when provided as part of a universal access service, the out-of-hours service is more likely to be based on telephone advice with the possibility of being advised to attend for treatment out-of-hours, usually at the dentist's own practice. Universal access services are also more likely to be available from Monday to Friday.

Emergency treatment sessions

In more than half (74) of UK health authorities there are designated emergency treatment sessions, at least at weekends (Table 1). In most areas (48 of 55 authorities) where there are separate services for unregistered patients, they are provided as designated emergency treatment sessions. Universal-access weekend arrangements are less likely to include designated treatment sessions (26 out of 44 authorities). In almost all areas treatment sessions are held in clinics or surgeries which have a fixed location (Table 2). This often means that patients get seen on a walk-in basis (ie without needing to make an appointment). However, to minimise attendance by people with less urgent dental problems some fixed location clinics insist that attenders telephone in advance to make an appointment. There were designated treatment sessions on weekday evenings in only 19 authorities.

Advice over the telephone

In only one authority were services restricted only to telephone advice. However, where services for CDS patients were organised separately it was often an advice line with little or no scope for treating patients out-of-hours. The provision of telephone advice was rarely an explicit feature of services intended only for unregistered patients.

In contrast, out-of-hours care in 26 of the 44 areas with universal access services is based primarily upon telephone advice, with the facility to offer treatment at the discretion of the dentist. Where there was no designated treatment session (16 authorities) any treatment offered was almost always in the dentist's own surgery. Where the telephone advice service was combined with a designated treatment session (10 authorities) the treatment sessions were more likely to take place in NHS premises such as CDS clinics (4 authorities) or hospital dental suites (1 authority). Typically such services were large LDC and/or health authority organised rotas which had made a local commitment to seeing unregistered as well as their own registered patients. The hours of advice are shown in Table 3.

Call-handling

Under most arrangements out-of-hours calls are usually either to mobile phones, pagers, or telephone answer-machines. However in a total of 47 areas it was reported that during certain periods calls were taken by a receptionist or other call-handler. Call-handling or screening was the most likely service to be carried out by external organisations such as ambulance trusts, GP co-operatives, or various private call-handling/dental deputising services – HealthCall being the most commonly mentioned. Although the majority of rotas and out-of-hours services still used a combination of pagers, mobile phones and answer-phones, introducing telephone triage was the most commonly mentioned service change being considered (see Table 4).

Services for CDS patients

Generally informants did not mention any formal out-of-hours arrangements specifically for CDS patients. Where such arrangements were mentioned, there was sometimes a telephone advice line for CDS patients, a more formal arrangement between the CDS and a particular practice or an informal agreement to accept CDS patients on the main local GDP rota. Sometimes this was on the understanding that CDS dentists take part in the rota. The reported lack of specific arrangements for CDS patients was often said to reflect the negligible level of out-of-hours demand from this class of patient. Employee indemnity issues surrounding CDS dentists re-opening NHS premises at night or at weekends were also perceived to partly explain the lack of formal arrangements for CDS patients.

Discussion

As with a similar survey of out-of-hours medical services11 which used semi-structured telephone interviews the overall response rate is very high (100% of authorities), and nearly 100% for the key variables, but data relating to other aspects of the services was much less complete. The main findings show that the provision of out-of-hours dental care is highly geographically variable, particularly services for unregistered patients. At one extreme some areas have highly organised, separately funded rotas run jointly by the health authority and the LDC, staffed by the majority of the dentists in the area, and providing either advice or treatment out-of-hours for all patients regardless of registration status. At the other extreme there are a number of authorities where there are no formal services for unregistered patients whatsoever: 25 authorities with no formal services at weekends, and 82 with none on weekday nights.

The implications of this should not be over-emphasised: unequal provision does not in itself constitute inequity of access. In many of these areas the lack of formal service arrangements for unregistered patients could reflect a genuine lack of demand. In contrast to general medical services there appears to be no widespread historical expectation that dentists are available outside normal surgery hours. Also it is usually acknowledged that while many rotas or other out-of-hours dental services nominally exist to serve their registered patients, it may be that unregistered patients with 'genuine' dental emergencies are rarely turned away. It is in any case usually impossible for dentists receiving a call out-of-hours to confirm anybody's registration status.

In other respects this situation may not be either sustainable or acceptable. The continuing shift away from NHS practice17,18 may undermine the goodwill whereby many unregistered patients currently receive care out-of-hours on an ad hoc basis. In a policy climate where the principle of universal access on the basis of need has been re-affirmed19 it is also questionable whether people should be denied access to emergency care, simply because of where they live and because their emergency problem happens to be in their mouth.

Limitations of the survey

Where the services or other entities to be studied are known to be complex and highly varied, and have not been previously described in any detail, it is not usually possible to ask standard questions which will make sense in all circumstances. Using semi-structured interviews allowed respondents to describe only those aspects of services relevant to their local situation. This conversational approach led to very high levels of co-operation. Interviewees also volunteered local experiences and opinions about the past development, current use and future plans relating to out-of-hours dental care.

However, it was also not possible to clarify all responses and ambiguities in a telephone interview of 10 to 30 minutes length. For example, while some respondents claimed services in their area were 'strictly for emergencies only' or 'for registered patients only' it was usually impossible to establish what this meant in practical terms: did all dentists apply a common definition of what constitutes a dental emergency, and are 'non-emergencies' always turned away? How can dentists distinguish who is and who isn't registered out-of-hours? And to what extent do dentists see non-emergencies or unregistered patients at their own discretion?

It is also slightly artificial to analyse the out-of-hours dental services in an area separately from other dental service arrangements - for example from services at other times, services in adjacent areas or from arrangements for holiday cover. In eight health authorities flexible arrangements for dealing with emergencies during normal surgery hours were thought to reduce the need for formal out-of-hours care arrangements. Examples include special emergency treatment sessions on Mondays to overcome weekend backlogs, and short emergency sessions at the beginning and end of each working day. In the Aylesbury Personal Dental Service pilot the latter strategy has reportedly almost eliminated the need for out-of-hours treatment during weekdays.20

Cross-border patient flows were mentioned in relation to the arrangements in 15 health authorities, especially in large cities where there were historically well-established and well-known hospital-based services. Manchester Royal Infirmary was mentioned as a popular source of emergency dental care in three health authorities. In some areas the perceived need for formal services was also increased by seasonal or daily influxes of tourists and commuters.

Changes in service provision

The development of formal out-of-hours services — involving the majority of dentists or practices in the same arrangements — was variously attributed to the existence of a 'core of well-informed well-motivated dentists' who 'get the ball rolling', the existence of a critical mass of patients using the service, as well as — in one instance — the need to reduce complaints from the local medical committee. Where large out-of-hours rotas had been established, the on-call frequency often reduced to 1 week/weekend in every 1 or 2 years. In such circumstances it was reported that few dentists wished to revert to out-of-hours arrangements involving greater amounts of time on-call. However, for geographical or personal reasons some dentists or practices still chose to make their own arrangements — 'to concentrate on their own patients', or so that their patients would not need to travel excessive distances for care under a larger rota.

In more rural or remote areas, where the main towns perhaps have only one or two dental practices, the continuation of services for unregistered patients may be strongly determined by the family and financial circumstances of just a few, or even one dentist. Dentist recruitment problems in rural areas were thought to be exacerbated when in 'unglamorous regions'. The ten areas which explicitly used NHS salaried dentists to staff emergency dental services were all large rural areas. However, the large distances between much of the population and main towns in such areas was also thought to substantially reduce the level of demand for out-of-hours dental care.

Some interviewees also cited circumstances which in their view had prevented the emergence or caused the discontinuation of out-of-hours services, in particular the general morale of local dentists. One believed that this 'intangible goodwill factor' made their arrangements 'vulnerable to sudden collapse'. In another area an emergency dental service had ended (and was not replaced) when the 1992 GDS fee reduction was introduced, and in two other areas dentists committed themselves more exclusively to their registered patients apparently in reaction to the imposition of the 1990 contract. Future research about these services might explore the importance of dentists' morale as a pre-requisite for certain service arrangements.

Planned service changes

A fifth (24) of UK health authorities were planning changes in their local arrangements, usually towards services which would be available at more times, to more people or from centralised premises (Table 4). It is difficult to know whether this level of change is caused by increasing demand, or whether it has been stimulated in part by the dramatic shifts in the way out-of-hours primary medical services are organised.

Future research

The survey has established the usefulness of some basic criteria for describing out-of-hours dental care arrangements: intended clients, availability of advice or treatment, days and times of service, staffing, and treatment setting. A detailed description of the out-of-hours care arrangements specifically for registered patients would require a survey of practices or dentists rather than health authorities. Any future surveys might also seek to collect more detailed information on: the types of care offered and not offered, the exact way in which calls are handled, the local balance of provision under private and NHS terms, how much patients pay, the proportion of patients which end up being examined or treated out-of-hours, and some measure of the geographical coverage of services. Given the direction in which services appear to be changing there is a particular need to understand the relative effectiveness of, and patient satisfaction with, telephone advice compared with treatment services. Ultimately the cost-effectiveness of different service arrangements will need to be carefully evaluated from both the patients' and NHS/service perspectives.

It is possible to identify several broad types of service organisation at the health authority level, on the basis of their intended clients and the level of service offered. Most services intended for unregistered patients only (45 of 55 authorities) and some (16 of 44) of the universal access services are limited to treatment sessions only. In contrast, services for registered patients are dominated by telephone advice, with the option for dentists to re-open their surgeries when they see fit. However to identify such main types of service would conceal the wide variety of arrangements in terms of staffing and remuneration arrangements, treatment settings, hours of availability, and geographical coverage.

Conclusions

The Acheson report has justifiably renewed attention on inequalities in oral health,21 but inequitable access to NHS dental services is still a major policy and public concern. This survey has revealed extremely wide geographical variation in the organisation of out-of-hours dental services provided in the United Kingdom.

Our findings suggest that of the around 29 million people in the UK who were not registered with an NHS dentist in 19981,2,3 there were no formal out of hours dental care arrangements for as many as 5 million of them at weekends (25 authorities), and 19 million on weekday nights (82 authorities). It is inconceivable that this lack of formal service provision does not translate into inequitable access to care in many areas. When unregistered patients in these areas need emergency dental care out-of-hours they are therefore likely to pay more, travel further, resort to seeing a doctor, or simply wait for surgeries to reopen before getting to see a dentist.

With the ongoing expansion of NHS Direct advice lines and emerging initiatives such as emergency walk-in centres there is likely to be increasing pressure on health authorities to rationalise out-of-hours emergency dental care and integrate it more fully with other primary care services.22 Furthermore if the levels of adult registration with NHS dentists continue to decline — from about 23 million to 18 million since 1994 (in England and Wales)23 — then the need to make formal out-of-hours service arrangements for unregistered patients may also increase. This study has revealed an extremely wide range of starting points for this process in different parts of the UK.

The voice of the BDA

A selection of news releases from the BDA's Press and Parliamentary Department.

New edition of Pictures for Patients

The British Dental Association has published a second edition of Pictures for Patients, due to popular demand. Based on the material developed by the Danish Dental Association, Pictures for Patients contains more than 200 photographs and diagrams which are helpful to dentists in explaining treatment procedures to patients.

The second edition contains a new orthodontics section featuring a variety of pictures on functional and fixed appliance treatments that are ideal for dentists to use as an image guide when referring patients for orthodontic treatment. Pictures for Patients is available at £49. Dentists who already have the first edition can buy a 16 page update pack with 40 new photographs for £12. All prices include postage and packaging. Contact Rowena Smith or Vicki Broome in the Education and Science Dept on 0171 935 0875 ext 234/277 for details. Orders can also be placed by post.

GDSC election results: Kravitz re-elected

Anthony Kravitz (Manchester) was re-elected Chairman of the BDA's General Dental Services Committee (GDSC) at their meeting on 28 January. Two new Vice-Chairman were also elected, Hew Mathewson from Edinburgh and Barry Cockcroft from Rugby. The GDSC now comprises 64 voting members, most elected on a constituency basis, plus a number of (non-voting) other members and observers. There are 14 new members for this triennium. Only 10 of the current GDSC were members in 1990.

Dr Kravitz said: 'I am delighted that the committee has shown their confidence in me by electing me to serve a further term as their leader. I pledge to work just as hard in future to try to improve the conditions of service for practitioners working in the GDS.'

BDA produces model CV software

The British Dental Association has brought out a contemporary piece of software in conjunction with Integrated Dental Holdings Ltd. The disk is designed to produce professional CVs and covering letters that will help dental students and recent graduates who are applying for jobs. The software accompanies the BDA advice sheet, Getting A Job, which contains all the relevant information on seeking work for dental students and recent graduates who are at the start of their practising careers. Available from the Association on disk or down loaded from the BDA Website, the software is compatible with PCs using Microsoft Word and is free to all members. It is part of the expanding service that the BDA offers students and young dentists and Getting A Job is one of four advice sheets produced for dental students, especially those in their last 2 years of university.

Advertising Standards Authority decision on title 'Dr'

The British Dental Association is disappointed with the Advertising Standards Authority's decision to uphold two complaints against dentists for using the title 'Dr' in adverts. The advertisements complied with the General Dental Council's guidelines and The Association believes that they made it clear that the advertiser was a dentist. However, in the ASA's opinion, the use of the title implied that the dentist was a general medical practitioner and dentists have been asked not to use the title in the future.

For further information, contact the BDA's Press and Parliamentary Department on 020 7935 0875 ext 243/258/299.

References

Digest of Statistics 1997/98 Part 1: Detailed Analysis of GDS Treatment Items. Eastbourne: Dental Practice Board, 1998.

Scottish Dental Practice Board Annual Report 1997/98. Edinburgh: Scottish Dental Practice Board, 1999.

Francis Gunning, Dental Directorate of Central Services Agency Northern Ireland (Personal Communication). 1997/98 recalled attendance and registration figures for Northern Ireland Health Boards, 1999.

Thomas D W, Satterthwaite J, Absi E G, Shepherd J P . Trends in the referral and treatment of new patients at a free emergency dental clinic since 1989. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 11–14.

Milsom K M, Zoitopoulos L . Community Dental Service based out of hours emergency dental care — A pilot study. Br Dent J 1993; 174: 177–178.

Anderson R, Richmond S, Thomas D W . Patient presentation at medical practices with dental problems: an analysis of the 1996 General Practice Morbidity Database for Wales. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 297–300.

Pennycook A, Makower R, Brewer A, Moulton C, Crawford R . The management of dental problems presenting to an accident and emergency department. J R Soc Med 1993; 86: 702–703.

Dickinson T M, Guest P G . An audit of demand and provision of emergency dental treatment. Br Dent J 1996; 181: 86–87.

Williams S J, Calnan M . Convergence and divergence: assessing criteria of consumer satisfaction across general practice, dental and hospital care settings. Soc Sci Med 1991; 33: 707–716.

Jessop L, Beck I, Hollins L, Shipman C, Reynolds M, Dale J . Changing the pattern of out of hours: a survey of general practice cooperatives. BMJ 1997; 314: 199–200.

Hallam L, Cragg D . Organisation of primary care services outside normal working hours. BMJ 1994; 309: 1621–1623.

Hallam L . Out of hours primary care: Variable service provision means inequalities in access and care. BMJ 1997; 314: 157–158.

Gorman A J, Edmondson H D . A study of the availability of emergency dental services in Birmingham. Dent Update 1995; 184–188.

Gibbons D E, West B J . DentaLine: an out of hours emergency dental service in Kent. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 63–66.

Crawford A N . Recalled dental attendance — its cost to the NHS. Br Dent J 1994; 179: 363–364.

Williams M . Emergency treatment provided by an FHSA-run clinic and the effect of the 1990 GDS contract on its use. Primary Dent Care 1995; 2: 51–54.

Taylor-Gooby P . Knights, Knaves, and Gnashers: professional values and private dentistry. Canterbury: University of Kent, 1999.

UK Dental Care: market sector report 1999. London: Laing & Buisson, 1999.

Department of Health. The new NHS: modern, dependable. London: Stationery Office, 1997.

Thomas D R (CDPH, Buckinghamshire HA). Personal Communication. June 1999.

Sir Donald Acheson . Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. London: Stationery Office, 1998.

Rogers A, Flowers J, Pencheon D . Improving access needs a whole systems approach. BMJ 1999; 319: 866–867.

Dental Practice Board. Dental Data Quarterly Bulletin: April–June 1999. Eastbourne: Dental Practice Board, 1999.

Acknowledgements

RA is jointly funded by the MRC and the Wales Office of Research and Development for Health and Social Care. Thanks should go to all the interviewees who supplied the information on which the study is based.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anderson, R., Thomas, D. Out-of-hours dental services: a survey of current provision in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 188, 269–274 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800452

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800452

This article is cited by

-

Adequacy and clarity of information on out-of-hours emergency dental services at Greater Manchester NHS dental practices: a cross-sectional study

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

A survey of dental school's emergency departments in Ireland and the UK: provision of undergraduate teaching and emergency care

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Identifying adults at risk of paracetamol toxicity in the acute dental setting: development of a clinical algorithm

British Dental Journal (2014)

-

Dental guidance for all

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Out-of-hours emergency dental services in Scotland – a national model

British Dental Journal (2008)