A shift from shelf fisheries to the deep sea is exhausting late-maturing species that recover only slowly.

Abstract

Criteria from the World Conservation Union1 (IUCN) have been used to classify marine fish species as endangered since 1996, but deep-sea fish have not so far been evaluated — despite their vulnerability to aggressive deepwater fishing as a result of certain life-history traits2. Here we use research-survey data to show that five species of deep-sea fish have declined over a 17-year period in the Canadian waters of the northwest Atlantic to such an extent that they meet the IUCN criteria for being critically endangered. Our results indicate that urgent action is needed for the sustainable management of deep-sea fisheries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

At one time it was presumed from the vastness of the oceans that fishing would not drive species to extinction. There have, however, been recent sharp declines in the numbers of oceanic cod, sharks, rays, tuna, marlins, swordfish and sea turtles3,4,5,6,7. As the shelf fisheries in the northwest Atlantic began to collapse in the 1960s and 1970s, harvesting shifted to deep-sea fish species8, but many populations crashed within ten years because their recovery is so slow2,9.

Deep-sea fish are highly vulnerable to disturbance because of their late maturation, extreme longevity, low fecundity and slow growth2,9. Some deep-sea fish form spawning aggregations on seamounts and the sea floor, and this increases their susceptibility to overfishing2. Survey data collected over extended periods are limited so it has been difficult to determine the effects of deep-sea fishing on both target and by-catch species.

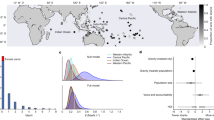

For our analysis, we chose five species that live on or near the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean, on the continental slope. They range from the common to the rare: roundnose grenadier, Coryphaenoides rupestris; onion-eye grenadier, Macrourus berglax; blue hake, Antimora rostrata; spiny eel, Notacanthus chemnitzi; and spinytail skate, Bathyraja spinicauda. The species evaluated can live to 60 years of age, grow to more than 1 m in length, and mature in their late teens. C. rupestris and M. berglax have been commercially fished, and all five are taken as by-catch in fisheries that target Greenland halibut, Reinhardtius hippoglossoides, and redfish, Sebastes spp. None was taken in any substantial number, even as by-catch, before the 1970s.

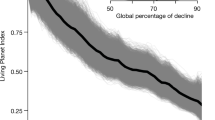

We used catch data from standardized, research-trawl surveys in the Canadian waters of the northwest Atlantic Ocean over 1978–94 to determine declines in relative abundance and individual mean size (for details, see supplementary information). All species declined in relative abundance (Fig. 1): declines over the 17-year period were 87–98% and declines estimated for three generations, the IUCN benchmark, were 99–100% (see supplementary information). Survey data for an additional period (1995–2003) were obtained for C. rupestris and M. berglax. The overall declines in relative abundance for these two species over the 26-year period were 99.6% and 93.3%, respectively; estimated declines over three generations were 100% and 99.7%, respectively (see supplementary information).

According to the IUCN criteria, these five species of deep-sea fish qualify as critically endangered in the northwest Atlantic. The declines occurred on a timescale equal to, or slightly less than, a single generation of these species. All of the species apart from N. chemnitzi also declined by 25–57% in mean size over the 17-year period (see supplementary information). The survey data are not adequate for full assessment of the situation for other deep-sea fish species that may also be at risk. The largest deepwater skate in the northwest Atlantic — the barndoor skate Dipturus laevis — was driven unnoticed almost to extinction6.

Scientific investigation lags behind the collapse of deep-sea fisheries8,9. Conservation measures are necessary and lack of knowledge must not delay appropriate initiatives, including the establishment of deep-sea protected areas.

References

World Conservation Union IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1 (2001).

Koslow, J. A. et al. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57, 548–557 (2000).

Pauly, D. et al. Nature 418, 689–695 (2002).

Myers, R. A. & Worm, B. Nature 423, 280–283 (2003).

Baum, J. K. et al. Science 299, 389–392 (2003).

Casey, J. M. & Myers, R. A. Science 281, 690–692 (1998).

Graham, K. J., Andrew, N. L. & Hodgson, K. E. Mar. Freshwat. Res. 52, 549–561 (2001).

Haedrich, R. L., Merrett, N. R. & O'Dea, N. R. Fish. Res. 51, 113–122 (2001).

Moore, J. A. & Mace, P. M. Fisheries 24, 22–23 (1999).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devine, J., Baker, K. & Haedrich, R. Deep-sea fishes qualify as endangered. Nature 439, 29 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/439029a

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/439029a

This article is cited by

-

Maturation and reproduction of Squalus cubensis and Squalus cf. quasimodo (Squalidae, Squaliformes) in the southern Caribbean Sea

Ichthyological Research (2019)

-

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents as natural egg-case incubators at the Galapagos Rift

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Trophic ecology of a deep-sea fish assemblage in the Northwest Atlantic

Marine Biology (2017)

-

Seasonal Reproductive Biology of the Bignose Fanskate Sympterygia acuta (Chondrichthyes, Rajidae)

Estuaries and Coasts (2015)

-

By-Catch Impacts in Fisheries: Utilizing the IUCN Red List Categories for Enhanced Product Level Assessment in Seafood LCAs

Environmental Management (2013)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.