Abstract

In cooperatively breeding vertebrates, indirect fitness benefits1,2 are maximized by subordinates who choose to help their own closely related kin after accurately assessing their relatedness to the group's offspring3,4,5. Here we show that in the cooperatively breeding Seychelles warbler (Acrocephalus sechellensis), female subordinates help to raise new nestlings by providing them with food only when the offspring are being raised by parents who also fed the subordinates themselves when they were young3. These helper females use the continued presence of the primary female, rather than of the primary male, as their provisioning cue — presumably because female infidelity is rife in this species6, making their relatedness to the father less reliable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In A. sechellensis, female offspring normally become subordinate within their natal group7,8 and often help to raise dependent young7. We studied the provisioning behaviour (feeds given per hour) of 21 colour-ringed female subordinates. Reproductive sharing and high levels of extra-pair paternity occur in this species6; we therefore assessed parentage and genetic relatedness by using microsatellite DNA markers8. Subordinate parents (that is, subordinates who had also produced a nestling in the helped nest) always provisioned and were excluded from subsequent analysis (n = 8).

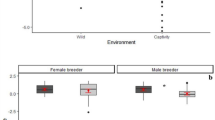

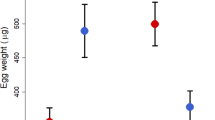

In a general linear model analysis, the provisioning behaviour of non-parent subordinates was influenced positively by subordinate–nestling relatedness (F1,11 = 4.82, P = 0.05, R2 = 0.31), whereas subordinate age, sex, number of nestlings, number of subordinates (or feeding adults) and territory quality had no significant effect. A comparison of relatedness9 to the nestlings of subordinates who helped with those that did not (Fig. 1a) indicates that helpers were significantly related to nestling(s), whereas non-helpers were not (mean relatedness, 0.27 versus −0.05, respectively).

a, Provisioning in relation to the pairwise relatedness between subordinates and nestlings (subordinate helper–nestling relatedness versus non-related: 0.27 ± 0.16 versus 0, one-sample t-test, t7 = 4.64, P < 0.002; helpers versus non-helpers: 0.27 ± 0.16, n = 8 versus −0.05 ± 0.20, n = 5; t11 = 3.13, P = 0.01). b, Provisioning in relation to the presence (purple bars) or absence (green bars) of the subordinate's putative parents (presence versus absence of putative mother: 7.57 ± 2.44, n = 6 versus 1.43 ± 3.60, n = 7; t-test, t11 = 3.71, P = 0.003; presence versus absence of putative father: 4.30 ± 4.89, n = 4 versus 4.24 ± 4.29, n = 8; t11 = 0.02, P = 0.98). Error bars, means ± s.e.; asterisks indicate statistical significance.

The continued presence of the primary female, but not of the primary male, was a reliable cue of subordinate–nestling relatedness; subordinate–primary female relatedness predicted subordinate–nestling relatedness (F1,38 = 27.37, P < 0.001), but subordinate–primary male relatedness did not (F2,37 = 2.11, P = 0.16). Subordinates provisioned significantly more often when their putative mother was still present, but provisioning was unaffected by the presence or absence of the putative father (Fig. 1b).

Subordinates may determine when to provision by directly assessing their relatedness to either the nestling(s) or the primary female. However, the continued presence of the primary female explained provisioning more reliably (F1,11 = 13.72, P = 0.003, R2 = 0.55) than genetic estimates of subordinate–nestling or subordinate–primary female relatedness (F1,11 = 2.14, P = 0.17; F1,11 = 0.06, P = 0.81, respectively). These results confirm that the presence of the primary female who raised the subordinate is likely to be used as a cue to determine when to provision. Previous findings that helpers can distinguish between siblings and half-siblings3 may have been an artefact caused by helpers assisting only their mothers.

Our results show that female subordinates can use an indirect but reliable cue to assess their relatedness to nestlings, and that this assessment of kinship determines provisioning rates. In A. sechellensis, the amount of food brought to the nestling determines fledging success and first-year survival, and the presence of a helper increases the number of young who are fledged on a territory10. The preferential provisioning of related nestlings by female subordinates will therefore increase the number of related offspring produced. In our study, the number of fledglings produced on a territory increased significantly (by 17%) for each subordinate present (after exclusion of direct parentage)8.

Both direct8 and indirect benefits may be important within this cooperative breeding system as, by using effective discrimination, subordinates are able to maximize the indirect benefit gained within a system that is driven primarily by direct benefits8. Our findings show that, in the presence of a high frequency of female infidelity, an associative learning mechanism has evolved to focus on the mother at the nest — the only sex to which the subordinates are reliably related.

References

Hamilton, W. D. J. Theor. Biol. 7, 1–52 (1964).

Emlen, S. T. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 8092–8099 (1995).

Komdeur, J. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 256, 47–52 (1994).

Russell, A. F. & Hatchwell, B. J. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 2169–2174 (2001).

Hatchwell, B. J., Ross, D. J., Fowlie, M. K. & McGowan, A. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 885–890 (2001).

Richardson, D., Jury, F., Blaakmeer, K., Komdeur, J. & Burke, T. Mol. Ecol. 10, 2263–2273 (2001).

Komdeur, J. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 263, 661–666 (1996).

Richardson, D. S., Burke, T. & Komdeur, J. Evolution 56, 2313–2321 (2002).

Goodnight, K. F. & Queller, D. C. Mol. Ecol. 8, 1231–1234 (1999).

Komdeur, J. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 34, 175–186 (1994).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richardson, D., Komdeur, J. & Burke, T. Altruism and infidelity among warblers. Nature 422, 580 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/422580a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/422580a

This article is cited by

-

Testing the environmental buffering hypothesis of cooperative breeding in the Seychelles warbler

acta ethologica (2023)

-

Breeders that receive help age more slowly in a cooperatively breeding bird

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Extra-pair parentage and personality in a cooperatively breeding bird

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (2018)

-

Avian β-defensin variation in bottlenecked populations: the Seychelles warbler and other congeners

Conservation Genetics (2016)

-

Sequential polyandry through divorce and re-pairing in a cooperatively breeding bird reduces helper-offspring relatedness

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.