Abstract

Nevi with architectural disorder and cytologic atypia of melanocytes (NAD), aka “dysplastic nevi,” have varying degrees of histologic abnormalities, which can be considered on a spectrum of grades of atypia. Somewhat controversial and subjective criteria have been developed for grading of NAD into three categories “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe.” Grading involves architectural and cytological features, which often correlate with each other. Architectural criteria were intraepidermal junctional extension beyond any dermal component, complex distortion of rete ridges, and dermal fibrosis. Cytological criteria were based on nuclear size, dispersion of chromatin, prominence of nucleoli, hyperchromasia and variation in nuclear staining. Few tests have been made of the relationship between specific grades of atypia and patient risk for melanoma. Retrospective review of pathology reports was performed on 20,275 nevi examined between 1989 and 1996. From the total, 6,275 were diagnosed as NAD, which were in 4,481 patients. These patients were divided into those whose worst NAD was mild (2,504), moderate (1,657), or severe (320). Review of accession data revealed that a personal history of melanoma was present in 5.7% of patients with mild, 8.1% with moderate, and 19.7% with severe atypia. The male/female ratios were similar in each group. In the three groups, the mean ages of men were similar and of women were similar, but the mean age of men tended to be 6–11 yrs. older than women in each group. Family histories of melanoma were not considered. The odds ratio as a measure of association between NAD and personal history of melanoma, shows an odds ratio of 4.08 (2.91–5.7) for NAD-severe versus NAD mild, odds ratio 2.81 (2–3.95) for NAD-severe versus NAD-moderate and odds ratio 1.45 (1.13–1.87) for NAD moderate versus NAD-mild. These data show that the probability of having personal history of melanoma, for any given NAD patient, correlates with the NAD grade. Likewise, the risk of melanoma is greater for persons who tend to make nevi with high grade histological atypia.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Since the histological description of a type of atypical nevus by Clark et al. (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), considerable controversy has surrounded the interpretation of the histological changes, regarding their correlation with familial melanoma and with melanoma risk for the individual. Subsequent work has emphasized two types of clinical settings associated with these atypical nevi, one being in patients with large numbers of such nevi and a familial or personal history of melanoma, called familial dysplastic nevus syndrome. The other setting involves patients with a variable number of such nevi and without any familial history of melanoma, which was called the sporadic dysplastic nevus syndrome (5, 9, 10, 11). Clark himself did not grade the histological changes seen in the atypical nevi, but he did not object to the attempts of others to do so (12, 13, 14, 15). In general, melanoma risk in patients has been found to be slightly elevated in association with the overall number of dysplastic nevi, without much consideration of the histological features of individual nevi (5, 11, 16, 17). Also, the basic definition of the dysplastic nevus and its relation to early melanoma have been so challenged that two NIH consensus conferences were convened, in 1984 and 1992, to deal with these problems and to suggest an improved terminology (18, 19). It was recommended that these lesions be defined clinically as “atypical nevi” and, histologically, as “nevi with architectural disorder and cytological atypia of melanocytes” with an estimation of the grade of atypia, rejecting the use of the term “dysplastic nevus” (19). Estimates of the frequency of atypical nevi associated with melanoma have found that approximately 39% of patients with melanoma have clinically atypical nevi, compared with 7% of a nonmelanoma control group (10). The relatively low frequency of melanoma associated with atypical moles in the absence of a family history of melanoma (20) contrasts with the relatively large number of patients who have clinically atypical nevi, that histologically fit the description of nevi with architectural disorder and atypia of melanocytes. One careful study of predominantly Caucasian patients in the Napa Valley of California estimated that approximately 4% of that population had “dysplastic nevi,” now called “nevi with architectural disorder and cytologic atypia of melanocytes” (13, 21). Obviously, only a few “dysplastic” nevi fit the category of “obligate precursors” of melanoma, as described by Clark et al. (8) and Tong et al. (22), and most “dysplastic nevi” are markers of increased melanoma risk, in general, for that individual (10, 20). Consequently, the hypothesis that we chose to test in the current study was that the grade of atypia of the nevus has some correlation with the risk of developing melanoma in that patient. If this hypothesis is true, it could be important in deciding the treatment options for that patient and lead to other, more basic studies of the nature of the underlying biochemical and genetic abnormalities responsible for the elevated melanoma risk. The ideal study of this type would define the level of abnormality for each nevus and then follow each patient throughout his or her lifetime, to determine whether or not he or she ever developed a melanoma. Such a study cannot be done within the lifetime of a single investigator and must be done by a case registry, over a long period of time. As a compromise, we chose to examine whether the grade of abnormality in the nevus had any relation to whether the patient had a personal history of melanoma at the time of the removal of the atypical nevus. If, indeed, histological grading of nevi has a correlation with melanoma risk, then high-grade atypia should be observed more frequently in patients who have a prior history of melanoma, as well as in patients who later develop a melanoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Definitions

Biopsies of melanocytic nevi have been classified routinely as to whether or not they exhibited architectural disorder and cytological atypia of melanocytes (“dysplastic nevi”) at the New York Hospital-Weill Medical College of Cornell University from 1983 to the present time. During that time, all nevi that were considered to have architectural disorder were graded into three grades based on an overall assessment of the degree of atypia of the nevus. The words “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe” were used for these three grades in the pathology reports on these specimens. The basis of this classification followed, in part, the recommendations of Mihm and colleagues (22, 23) with regard to the cytological classification. However architectural criteria also had to be included. How these criteria were used in our laboratory can be summarized in tabular form (Table 1). Crowson, Magro, and Mihm published recently a very detailed description, with extensive illustrations, of mild, moderate, and severely “dysplastic” nevi that corresponds well with the criteria that we used in our classification, based on earlier publications by Mihm (24). A brief description of our criteria follows:

All of the “dysplastic” nevi or nevi with architectural disorder (NAD) in our series had the following features: extension of the junctional component at least three rete ridges beyond any dermal component, papillary dermal fibrosis, elongation and distortion of rete ridges, and a variable lymphocytic infiltrate. Mild NAD and moderate NAD mostly were rather symmetrical lesions that were well circumscribed. Severe NAD tended to lack exact symmetry but were well circumscribed in the epidermis. In mild and moderate NAD, the individual nevus cells and nests of nevus cells were mainly on the elongated, distorted rete, without much involvement of the suprapapillary plates. Severe NAD had more suprapapillary plate involvement, especially in the centers of the lesions, but lacked pagetoid upward migration or irregular spread in the epidermis. Cytologically mild NAD, moderate NAD, and severe NAD differed in the following characteristics at high magnification.

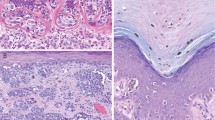

Mild Cytological Atypia

For this study, mild cytological atypia was defined at high magnification. (Fig. 1, A–B) The nuclei of the melanocytes were condensed, ovoid-to-ellipsoidal in shape, hyperchromatic, indented, and often without a visible nucleolus, or with a very small one. There was considerable variability in nuclear shape. The cytoplasm was often collapsed to form a clear space, or halo, around the cell. For classification purposes, these cytological features were usually judged on the appearance of the junctional extension zone. Pagetoid upward migration of melanocytes was absent or minimal and not at the edges of the lesion. Mitoses were absent from any dermal component of the nevus.

A, nevus, compound type, with architectural disorder and mild cytologic atypia of melanocytes. This region shows the extension of the junctional component beyond the dermal component, with some papillary dermal fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltration but with only slight distortion of the rete ridges and with nevus cells that generally do not have nuclei larger than the keratinocyte nuclei nearby (H&E, 10 ×). B, the nuclear size in the nevus cells is near that in the keratinocytes (H&E, 40 ×).

Moderate Cytological Atypia

At high magnification, the nuclei of the nevus cells are quite variable in size and chromatin patterns. (Fig. 2, A–B) Many nuclei are enlarged to the size of those in basal keratinocytes, have hyperchromatic staining with an ellipsoidal or rhomboidal shape, and often have a small nucleolus visible in the center of the nucleus. The cytoplasm is frequently enlarged, compared with that of the resting melanocyte, and may not collapse on fixation to show a “halo” around the cell. Atypical mitoses are absent in the intraepidermal component, and even typical mitoses are also absent in the deepest dermal component. Very few normal-appearing mitoses can occur in the upper dermal part of the nevus, near the epidermis or appendageal epithelium.

A, nevus, compound type, with architectural disorder and moderate cytologic atypia of melanocytes. This region also has extension of the junctional component beyond the dermal portion. There has been partial regression of the dermal component. The rete ridges are quite distorted, and the nuclei in the nevus cells are enlarged (H&E, 10 ×). B, the enlargement and hyperchromasia of the nevus nuclei is more evident at higher magnification of this lesion, which is overall at the high end of the scale of moderate atypia. A few cells in this photo have sufficient atypia to be classified as severe atypia (H&E, 40 ×).

Severe Atypia

Nests of nevus cells predominate over the individually dispersed nevus cells, although at the center of the lesion, some upward migration of individual nevus cells can occasionally be found upon careful search. Upward migration is not present at the periphery of the lesion. The dermal component tends to be abundant, and nests are more crowded than in the lower grade atypias. Stroma intervenes between the nests and contains collagen, with melanophages, and lymphocytes. At high magnification, the main distinguishing features of the severe atypia become evident. (Fig. 3, A–B) The nuclei of the nevus cells are enlarged and usually larger than those in the keratinocytes. Often there is an admixture of cells that include large bizarre hyperchromatic nuclei with smaller nuclei, having dispersed chromatin. There is not confluent atypia, as would be expected in a melanoma. Nucleoli are often prominent. These characteristics may be found in both spindle-shaped nuclei and in rounded or epithelioid nuclei. Mitoses often are moderately easy to find in the junctional component, but it is noteworthy that they are absent from any deep, dermal component of these nevi in adults. The dermal portion lacks confluent atypia and tends to show defective or only focal maturation in the dermis.

A, nevus, compound type, with architectural disorder and severe cytologic atypia of melanocytes. Rete ridge fusion is extensive with papillary dermal fibrosis and lymphocytic and melanophage infiltration. Many of the nuclei in the nevus cells are enlarged (H&E, 10 ×). B, the nuclei are more expanded, and nucleoli are more prominent than those in the moderate degree of atypia. The cytoplasm also is more abundant (H&E, 40 ×).

Modification of these criteria is necessary in certain cases. When nevi appear in small children, usually in prepuberal children, the nevus nests are large, and nevus cell size and nuclear size can be quite large, with prominence of nucleoli. These features can be found in ordinary congenital and acquired compound nevi that are not Spitz nevi. Cytological atypia can be evident focally. If these lesions are distinguishable from Spitz nevi, then they can be classified as NAD. We have tended to downgrade the overall evaluation of atypia from severe to moderate or from moderate to mild in young children because of these age-related differences in nevus cell size. In contrast, because we gave only one overall grade of atypia for each lesion, an upgrading of overall atypia was necessary when severe architectural disorder was present, especially pagetoid upward migration at the periphery of the lesion. This upward migration, in combination with severe or moderate cytological atypia, is often an important indication of the presence of malignant melanoma in situ in the epidermis. Also, the detection of mitoses at the base of the dermal component of any of these lesions, with moderate or severe cytological atypia, causes a modification of the classification, usually to an invasive malignant melanoma. Spitz nevi need to be excluded but usually do not have mitoses at the base of the dermal portion of the nevus. Occasionally, a deep mitosis in a clearly benign nevus is related to the fact that the nevus cells are near an epidermal appendage, which may lie slightly deeper in the paraffin block.

Selection of Case Material

Retrospective review of pathology reports was performed on a total of 20,275 melanocytic nevi that were received for routine diagnostic examination over an 8-year period between 1989 and 1996, inclusively. From this total, 6,275 were diagnosed as nevus with architectural disorder (NAD). Collation of these NAD by patient names and addresses showed that they were from 4,481 patients. These patients were classified into three groups based on their highest grade of atypia (minimal or mild, moderate, or severe) that was assigned at the time of the initial diagnostic examination, before any knowledge of the clinical history. Review of the accession data for each of these 4,481 patients was performed to determine whether or not a prior personal history of melanoma was given. On the patients with a history of melanoma, the age and gender were recorded. The age used for this evaluation was based on the time of submission of the lesion with the highest grade of atypia, or of that of the first lesion with the highest grade, in cases with multiple lesions of the same grade.

Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically treated, using the processes described as follows. (1) Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparing numerical data and qualitative data (categories). The data are expressed as the mean, with the standard deviation in parentheses. (2) The χ2 test was employed to compare the categories. (3) Odds ratio was calculated as a measure of association between NAD and a personal history of melanoma. The data are expressed as the odds ratio, with the 95% confidence limit in parentheses.

RESULTS

Of the 4481 patients with NAD, the worst NAD was mild in 2504 patients, moderate in 1657 patients, and severe in 320 patients. Review of the accession data showed that the submitting dermatologist mentioned a personal history of melanoma in 5.7% of those patients with mild NAD, in 8.1% of those with moderate NAD, and in 19.7% of those with severe NAD. These differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 59.89, P < .001; Table 2). The three groups were different in size. A prior personal history of melanoma was obtained in 142 patients in the mild NAD group, and this was 5.7%. In the moderate NAD group, the 133 patients with a personal history of melanoma were 8.1%. Likewise, in the severe NAD group, there were 63 patients with a personal history of melanoma, which was 19.7% of this smaller group. Family histories of malignant melanoma were not considered because the dermatologists gave these histories in 1989 and in 1990 but for some unknown reason spontaneously almost stopped giving any such family history thereafter. We did not find any such erratic change in the giving of personal histories of melanoma in the accession data.

The study of the odds ratio as a measure of association between NAD and personal history of melanoma showed an odds ratio of 4.08 (2.91–5.7) for severe NAD versus mild NAD, odds ratio 2.81 (2–3.95) for severe NAD versus moderate NAD and odds ratio 1.45 (1.13–1.87) for moderate NAD versus mild NAD. Consequently, the probability of any given patient with severe NAD having a personal history of melanoma is 4.08 times higher than a patient with mild NAD. Likewise, the probability of a patient with severe NAD having a personal history of melanoma is 2.81 higher than a patient with moderate NAD, and the probability of a patient with moderate NAD having personal history of melanoma is 1.45 times higher than a patient with mild NAD. (Table 3).

The patients with a personal history of melanoma in these three NAD groups were compared with regard to age. The melanoma patients were not very different in mean age (range), specifically those with mild NAD, who had a mean age of 45.9 years (16–88 y), whereas those with moderate NAD had a mean of 47.4 years (17–85 y). Those patients with severe NAD had a mean age of 48.9 years (21–88 y).

The male-female ratios were nearly 1:1 for the melanoma patients in each group of mild, moderate, or severe NAD. Specifically, the patients with a prior personal history of melanoma in the mild NAD group were 50.7% women, in the moderate NAD group they were 49.6% women, and in the severe NAD group, they were 44.4% women.

When the data on mean age of the melanoma patients in each NAD group were segregated into the ages of the men and the ages of the women, then a trend was evident, in that in each NAD group, men showed a slightly greater mean age than women. Specifically, in the mild NAD group, men with melanoma had a mean age of 49.9 years, and women, a mean age of 42.0 years. In the moderate NAD group, men had a mean age of 50.2 years, and women, of 44.4 years. In the severe NAD group, the men had a mean age of 52.2 years, and the women, 44.9 years (Fig. 4). These age differences in melanoma patients were statistically significant for those in the mild NAD group (P < .0025) and for the moderate NAD group (P < .025). In the severe NAD group, these differences were not significant (P = .07), perhaps because of the small size of the group.

DISCUSSION

The histological grading of lesions has historically been a rather subjective attempt to relate the degree of atypia to the degree of risk for the individual. Examples can be observed in early studies of the grades of cervical intraepidermal neoplasia (CIN) and the risk of cervical squamous carcinoma (25), or in Broder’s grades or other grading systems for invasive squamous cell carcinoma (26). When similar principles were applied to invasive melanomas, a type of subjective grade was initially produced by estimation of Clark’s levels or “anatomic levels,” based on the evaluation of the number of histological boundaries, that had been breached by the invasive melanoma cells (27). Breslow (28) gave the grade of invasive melanomas a more quantitative basis. Now the use of thickness measurements, in the style of Breslow, is common and has been incorporated into new methods for evaluating risk from invasive melanoma (29, 30). The evaluation of grades of atypia in nevi has been difficult because of the presence of a wide variety of morphological appearances of nevi and the presence of considerable nuclear atypia in some nevi that have a relatively benign clinical course in the great majority of cases. Examples of frequently atypical but benign nevi are Spitz nevi, nevi with architectural disorder (NAD), and “ancient nevi” that show a type of degenerative atypia, cellular blue nevi, and congenital nevi with proliferative foci in newborn children. The presence of such a variety of nevi that may have cytological atypia makes it essential to deal with them one type at a time with regard to any grading scheme relating to melanoma risk. In this study, we have concentrated on NAD and have tried to exclude other types of nevi from consideration. It is quite clear that there is a spectrum of atypia in NAD, which includes architectural atypia and cytological atypia of melanocytes. Many of the abnormal features of NAD correlate with each other (31, 32, 33). There are three basic groups: NAD with minimal criteria for classification, NAD with maximal criteria for classification, and NAD that are in the middle, showing an intermediate number of criteria. Barnhill (34) has suggested a similar division into low grade and high grade lesions as poles of a spectrum, with some lesions also in the middle. It is clear that any grading scheme cannot be purely architectural or purely based on cytological criteria, because there are melanomas with only moderate degrees of cytological atypia (for example, acral melanomas) and innocuous lesions with extensive architectural disorder (for example, recurrent compound nevi). We, and others, have tried to use schemes for such combined architectural and cytological evaluation of NAD (34). When lesions are excised completely, it is impossible to know what the risk of development of melanoma might have been if a specific NAD had been left undisturbed on the patient’s skin. Likewise, because a melanoma arising in a lesion tends to destroy any small precursor lesion, correlations of melanoma risk in a particular lesion depend on very early recognition of the initial stages of the melanoma, which has been infrequent. It has been estimated that melanomas arise in NAD, but with an overall frequency range from 10 to 40%. Reasonable agreement has been achieved on an estimate of 20% of melanomas arising in association with an NAD (18, 19, 20, 35, 36). It is difficult to grade the remnants of NAD, or in some instances even to recognize the exact border between the NAD and the melanoma arising in it. So grading of such remnants has not been done. Consequently, there have been few attempts to correlate melanoma risk for an individual with different grades of atypia in NAD. For these basic reasons, we have turned to an examination of the histories of patients as a measure of melanoma risk in association with different grades of atypia in NAD. Barnhill (36) has reasoned elsewhere that a certain threshold of cytological atypia must be reached to develop a melanoma. Moreover, because those NAD with high-grade atypia are closer to such a threshold, they would be expected to carry a greater risk than lesions of low-grade atypia. However, proof of this hypothesis has been difficult. Also two other studies have demonstrated that there is greater atypia in the NAD of patients with a melanoma than in those without a melanoma (37, 38). However, there have been other studies that have not found any such relationship (17, 34, 39), perhaps because of difficulties in agreement between those workers on the definition of a NAD (31). Despite the difficulties inherent in any retrospective study, we felt that there was something to be learned about the validation or invalidation of the hypothesis that severe atypia in NAD was more associated with melanoma risk than lesser grades of atypia in NAD. We also felt that if a sufficiently large population of patients was studied retrospectively, occasional erratic behavior on the part of the clinicians giving the patient history would be buffered and would be equally likely to affect the histories given, for any of the degrees of atypia of NAD. We were unable to use information about family histories of melanoma because of a sudden decrease in such histories from clinicians. However, we did not detect any such change regarding a prior personal history of melanoma in any patient. One advantage of the study is that the system for grading the NAD was employed rather uniformly at one institution, under the direction of a single director, for a period of >15 years and was not changed during the 8 years (1989–1996) selected for study here. Moreover, a large proportion of the melanomas were diagnosed at the same institution, but not all of them. Because the institution is not a particular referral center for melanoma treatment or diagnosis, there were few cases of melanomas diagnosed elsewhere for which the patients received follow-up examinations of their NAD. This was due to the nearby presence of three large centers for melanoma treatment at New York University, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the University of Pennsylvania. Consequently, we think that the principal conclusion that can be made from the study presented here, is that severe atypia of NAD is more associated with a patient risk of melanoma than lesser grades of atypia, despite the much more frequent removal of NADs with mild or moderate atypia. Although there is a spectrum from mild to severe atypia, we did not demonstrate any very striking difference between mild and moderate atypia in NAD as a marker of melanoma risk. We were unable to confirm any significant differences in patient ages in the mild, moderate, and severe categories, as noted by other investigators (15, 40), probably because we only tested statistically the ages of patients with both NADs and prior melanomas. In this retrospective study, we could not compare this grading scale with risk from other variables, such as the total number of nevi. Also, we did not study how to use this information about risk to make recommendations about surgical margins for individual grades of atypia in NAD. Because aneuploidy has been demonstrated in NAD (37, 41, 42), it is judicious for the most atypical NAD to be completely removed if possible. Other investigators have published their recommendations, which are reasonable ones (22, 24, 34). In the 6 to 13 years of follow-up on the patients included in this study, none developed melanoma at the exact site of the lesions that were studied here and classified as NAD. Our study only applies to a confirmation of an elevation in the general risk of melanoma in patients with various grades of atypia in NAD and thereby supports efforts toward future grading of these lesions.

References

Arumi Uria M . Nevus displásico: gradación de la atipia y correlación de la atipia con marcadores de proliferación y de migración celular. Barcelona, Spain: Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2001.

Clark WH Jr, Reimer RR, Greene M, Ainsworth AM, Mastrangelo MJ . Origin of familial malignant melanomas from heritable melanocytic lesions. “The B-K mole syndrome.” Arch Dermatol 1978; 114: 732–738.

Clark WH Jr . The dysplastic nevus syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1988; 124: 1207–1210.

Clark WH Jr, Elder DE, Guerry DIV, Epstein MN, Greene MH, Van Horn M . A study of tumor progression: the precursor lesions of superficial spreading and nodular melanoma. Hum Pathol 1984; 15: 1147–1165.

Elder DE, Goldman LI, Goldman SC, Greene MH, Clark WH Jr . Dysplastic nevus syndrome: a phenotypic association of sporadic cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 1980; 46: 1787–1794.

Reed RJ, Clark WH Jr, Mihm MC . Premalignant melanocytic dysplasias. In: Ackerman AB, editor. Pathology of malignant melanoma. New York: Masson; 1981. p. 159–183.

Greene MH, Clark WH Jr, Tucker MA, Elder DE, Kraemer KH, Guerry DIV, et al. Acquired precursors of cutaneous malignant melanoma. The familial dysplastic nevus syndrome. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 91–97.

Clark WH Jr, Elder DE, Guerry DPIV . Dysplastic nevi and malignant melanoma. In: Farmer ER, Hood AF, editors. Pathology of the skin. 1st ed. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1990. p. 684–756.

Elder DE, Greene MH, Bondi EE, Clark WH Jr . Acquired melanocytic nevi and melanoma. The dysplastic nevus syndrome. In: Ackerman AB, editor. Pathology of malignant melanoma. New York: Masson; 1981. p. 185–215.

Halpern AC, Guerry DI, Elder DE, Clark WH Jr, Synnestvedt M, Norman S, et al. Dysplastic nevi as risk markers of sporadic (nonfamilial) melanoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127: 995–999.

Elder DE, Murphy GF . Melanocytic tumors of the skin. Atlas of tumor pathology. 3rd series. Fascicle 2. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1991.

Mihm MC Jr, Googe PB . Problematic pigmented lesions. A case method approach. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990.

Kelly JW, Crutcher WA, Sagebiel RW . Clinical diagnosis of dysplastic melanocytic nevi. A clinicopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986; 14: 1044–1052.

Roth ME, Grant-Kels JM, Ackerman AB, Elder DE, Friedman RJ, Heilman ER, et al. The histopathology of dysplastic nevi. Continued controversy. Am J Dermatopathol 1991; 13: 38–51.

Sagebiel RW . The dysplastic melanocytic nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 20: 496–501.

Holly EA, Kelly JW, Shpall SN, Chiu S-H . Number of melanocytic nevi as a major risk factor for malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 17: 459–468.

Piepkorn MW, Barnhill RL, Cannon-Albright LA, Elder DE, Goldgar DE, Lewis CM, et al. A multiobserver, population-based analysis of histologic dysplasia in melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 30: 707–714.

Freinkel RK, Cage GW, Caro WA, Carter DM, Cole P, Elston RC, et al. Consensus Conference. Precursors to malignant melanoma. JAMA 1984; 251: 1864–1866.

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Early Melanoma. NIH Consensus Conference: diagnosis and treatment of early melanoma. JAMA 1992; 268: 1314–1319.

Carey WP Jr, Thompson CJ, Synnestvedt M, Guerry DIV, Halpern A, Schultz D, et al. Dysplastic nevi as a melanoma risk factor in patients with familial melanoma. Cancer 1994; 74: 3118–3125.

Crutcher WA, Sagebiel RW . Prevalence of dysplastic naevi in a community practice [letter]. Lancet 1984; 1: 729.

Tong AKF, Murphy GF, Mihm MC Jr . Dysplastic nevus: a formal histogenetic precursor of malignant melanoma. In: Mihm MC Jr, Murphy GF, Kaufman N, editors. Pathobiology and recognition of malignant melanoma. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1988. p. 10–18.

Rhodes AR, Mihm MC Jr, Weinstock MA . Dysplastic melanocytic nevi: a reproducible histologic definition emphasizing cellular morphology. Mod Pathol 1989; 2: 306–319.

Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC Jr . The melanocytic proliferations. 1st ed. New York: Wiley; 2001.

Kurman RJ, Norris HJ, Wilkinson EJ . Tumors of the cervix, vagina and vulva. Atlas of tumor pathology. 3rd series. Fascicle 4. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1992.

McKee PH . Pathology of the skin, with clinical correlations. 2nd ed. London: Times Mirror International; 1996.

Clark WH Jr, From L, Bernadino EA, Mihm MC Jr . The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res 1969; 29: 705–715.

Breslow A . Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg 1970; 172: 902–908.

Clark WH Jr, Elder DE, Guerry DPIV, Braitman LE, Trock BJ, Schultz D, et al. Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989; 81: 1893–1904.

Sagebiel RW . Problems in microstaging of melanoma vertical growth. In: Mihm MC Jr, Murphy GF, Kaufman N, editors. Pathobiology and recognition of malignant melanoma. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1988. p. 94–109.

Barnhill RL, Roush GC, Duray PH . Correlation of histologic architectural and cytoplasmic features with nuclear atypia in atypical (dysplastic) nevomelanocytic nevi. Hum Pathol 1990; 21: 51–58.

Duncan LM, Berwick M, Bruijn JA, Byers R, Mihm MC, Barnhill RL . Histopathologic recognition and grading of dysplastic melanocytic nevi: an interobserver agreement study. J Invest Dermatol 1993; 100 (3 Suppl): 318–321.

Shea CR, Vollmer RT, Prieto VG . Correlating architectural disorder and cytologic atypia in Clark (dysplastic) melanocytic nevi. Hum Pathol 1999; 30: 500–505.

Barnhill RL . Melanocytic proliferations with architectural disorder and cytologic atypia (melanocytic dysplasia and dysplastic nevi). In: Barnhill RL, Busam KJ, editors. Pathology of melanocytic nevi and malignant mela-noma. 1st ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995. p. 169–194.

Ackerman AB . Critical commentary on statements in “Precursors to Malignant Melanoma.” Am J Dermatopathol 1984; 6 (Suppl 1): 181–183.

Barnhill RL . Current status of the dysplastic melanocytic nevus. J Cutan Pathol 1991; 18: 147–159.

Bergman W, Ruiter DJ, Scheffer E, van Vloten WA . Melanocytic atypia in dysplastic nevi. Immunohistochemical and cytophotometrical analysis. Cancer 1988; 61: 1660–1666.

Black WC, Hunt WC . Histologic correlations with the clinical diagnosis of dysplastic nevus. Am J Surg Pathol 1990; 14: 44–52.

Ahmed I, Piepkorn MW, Rabkin MS, Meyer LJ, Feldkamp M, Goldgar DE, et al. Histopathologic characteristics of dysplastic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 22: 727–733.

Sagebiel RW, Banda PW, Schneider JS, Crutcher WA . Age distribution and histologic patterns of dysplastic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985; 13: 975–982.

Schmidt B, Weinberg DS, Hollister K, Barnhill RL . Analysis of melanocytic lesions by DNA image cytometry. Cancer 1994; 73: 2971–2977.

Kang S, Barnhill RL, Mihm MC Jr, Fitzpatrick TB, Sober AJ . Melanoma risk in individuals with clinically atypical nevi. Arch Dermatol 1994; 130: 999–1001.

Acknowledgements

Partially supported by Grant B.A.E. 97/5087 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria.

This work is a portion of the doctoral thesis of Dr. Arumi-Uria presented to the Faculty of Medicine at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain on October 22, 2001 (1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arumi-Uria, M., McNutt, N. & Finnerty, B. Grading of Atypia in Nevi: Correlation with Melanoma Risk. Mod Pathol 16, 764–771 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000082394.91761.E5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000082394.91761.E5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Melanocytic nevi and melanoma: unraveling a complex relationship

Oncogene (2017)

-

From melanocytes to melanomas

Nature Reviews Cancer (2016)