Abstract

Core needle biopsy is the preferred technique for evaluating breast masses and abnormal mammographic findings. The frequency of detection of noninvasive lobular lesions by core needle biopsy is increasing. Historically, the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ has been considered a risk factor for the development of invasive carcinoma, and treatment has consisted of careful clinical follow-up with or without chemopreventive therapeutic agents such as tamoxifen citrate. We retrospectively reviewed core needle biopsy material with the primary diagnoses of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and lobular neoplasia in conjunction with clinical and radiographic findings to make recommendations as to when excision may be merited. We searched our database for core needle biopsy cases with lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and lobular neoplasia as the primary diagnosis. Microcalcifications had been sampled with a stereotactically guided, 11 G Mammotome biopsy device, and masses had been sampled with an ultrasound guided, 18 G core needle. Glass slides were reviewed and histological parameters assessed. Mammographic findings were reviewed, and clinical information was obtained from the medical record. When available, excisional biopsy material was reviewed. The 2337 breast core needle biopsies performed from January 1995 to December 2001 included 35 (1.5%) with classic lobular carcinoma in situ (14), lobular neoplasia (4), and atypical lobular hyperplasia (17) as the primary diagnosis. Twelve of these 35 cases (34%) had histological evidence of microcalcifications directly associated with the lobular carcinoma in situ, lobular neoplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia. Radiologic review revealed 21 calcifications, 6 ultrasonographic masses, and 8 mammographic masses and/or architectural distortions. Excisional biopsy had been performed in 17 cases (49%). In six cases diagnosed as in situ on core needle biopsy, excisional biopsy revealed invasive carcinoma. All of these patients had radiographically detectable masses. Eleven cases had excisional biopsies that showed histology similar to that of the core needle biopsies. The most important predictor of invasive carcinoma on excision was a synchronous mass lesion. Lobular carcinoma in situ involving adenosis and lobular carcinoma in situ with pagetoid spread on core needle biopsies did not show a histologically more aggressive lesion on excision and, therefore, may not require additional surgery. Histologically identified calcifications were associated with lobular lesions 34% of the time; however, their presence inside an in situ lobular lesion did not portend worse pathology on re-excision and should not be a criterion for excision. Based on these findings, we recommend excisional biopsy of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular neoplasia only when it is associated with a synchronous mass lesion.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The increased use of screening mammography has resulted in an increasing number of image-guided breast biopsies of mammographically suspicious lesions. Core needle biopsy is an easy method of sampling small nonpalpable lesions and obtaining tissue for diagnosis. The improved mammographic detection of small and subtle (often nonpalpable) abnormalities has increased detection of in situ carcinomas and small invasive carcinomas, leading some to suggest that this in turn has decreased breast cancer mortality (1). In 1941, Foote and Stewart (2) described lobular carcinoma in situ as a lesion that is an incidental microscopic finding that could not be identified clinically or by gross examination. In 0.5–3% of surgical biopsy samples, lobular carcinoma in situ is the most significant finding (3, 4). Women with lobular carcinoma in situ have an elevated risk of developing invasive cancer in either breast (3, 5, 6, 7, 8), and their treatment has consisted of annual surveillance with or without chemopreventive agents (9). Currently, however, there are no standardized treatment guidelines for patients with lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed by core needle biopsy.

Herein, we describe the experience at our center with classic lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and lobular neoplasia detected mammographically, identified by core needle biopsy, and unassociated with a more worrisome pathologic entity. We review the findings on follow-up excisional biopsy of these lesions to identify histological and/or radiologic findings that when present, should prompt the pathologist to recommend excisional biopsy. We report the follow-up data up to 39 months on those patients not biopsied. Based on our data, we challenge the assertion that the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, or lobular neoplasia by core needle biopsy is unrelated to the mammographic abnormality that initiated the biopsy and thus inconsequential. We also show data that supports clinically following patients with lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy when the lesion is not associated with a mass.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

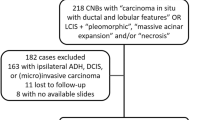

The pathology database at the University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center was searched, and the results of 2337 core needle biopsies from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2001 were retrospectively reviewed for cases with the primary diagnosis of classic lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular neoplasia. Thirty-five cases were identified. Lesions were re-reviewed and categorized based on published histological criteria (7, 8). For the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ, we required expansion of acini with atypical monotonous epithelial cells containing small, uniform nuclei and lacking pleomorphism or mitotic activity. For the diagnosis of atypical lobular hyperplasia, we required similar histological characteristics, with less pronounced distension of the terminal duct lobular units. The diagnosis of lobular neoplasia was reserved for those rare cases that had cytological features similar to those of lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia but that could not be definitively categorized either category either because of an underlying lesion such as adenosis or for a quantitatively borderline lesion. Cases were excluded from the study if there was co-existing invasive carcinoma, intraductal carcinoma, atypical intraductal hyperplasia, pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ, or necrosis as we routinely recommend excisional biopsies for these entities. Glass slides were reviewed and histological parameters were assessed including extent of disease, number of cores involved, presence of pagetoid extension and presence of microcalcifications. Attention was placed on where the calcifications were located. Clinical information was extracted from the patients' medical records.

Two types of core needle biopsies were evaluated in this study. Microcalcifications, masses, and architectural distortions had been sampled with stereotactic guidance using an 11 G, vacuum-assisted biopsy (Mammotome; Ethicon EndoSurgergy, Cincinnati, OH). Solid masses had been sampled with a sonographic-guided 18–20 G, cutting-needle biopsy (Biopty; Bard Urological, Covington, GA). Two to 10 (average, 4), ultrasound-guided specimens had been obtained per patient. The stereotactic biopsies had been performed with the patients prone on a dedicated table (LoRad, Danbury, CT). From January 1995, to March 1997, a 14 G cutting needle had been used while the patient was in an upright unit. The average number of vacuum-biopsy specimens per patient was 11 (range, 6 to 18). A 3-mm stainless steel clip had been routinely placed in the biopsy site after biopsies in which most of the calcifications were removed by sampling. Cores containing calcifications had been radiographed before processing, and cores determined to contain calcifications had been marked with ink.

Sonographically guided biopsies had been performed with the patients in the supine or supine-oblique position by using a 7.5 or VFX 13-MHz linear array transducer and high-resolution sonographic equipment (Siemens Sonoline, Mountainview, CA) in a dedicated breast-sonography unit. The number of core samples obtained was at the discretion of the dedicated breast radiologist performing the procedure and was based on visual inspection of the needle placement and tissue sections obtained. Stereotactic and ultrasound-guided biopsies were submitted in one to four blocks and levels were cut; at least two hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each block (some containing multiple levels) were evaluated.

Radiographic findings were reviewed to determine the mammographic features of each mass including whether architectural distortion or calcifications were present, size, and the American College of Radiology BI-RADS classification (10). Calcified lesions were classified as calcifications, and mass lesions containing calcifications were classified as masses.

When available, the excisional biopsy material was reviewed. The time to excisional biopsy was recorded. Specimen roentgenograms were obtained for all surgically excised material with architectural distortions or calcifications (Faxitron Cabinet X-Ray, Wheeling, IL).

RESULTS

Clinical

All 35 patients were women. Their ages ranged from 37 to 79 years (mean, 58 y). Fifteen women were premenopausal, and 20 were postmenopausal. Fourteen (40%) had a family history of breast carcinoma in a first- or second-degree female relative documented in their medical records. Fifteen (43%) of the women had synchronous or metachronous carcinoma in the contralateral breast.

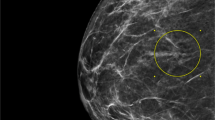

Radiographic

Review of the mammograms revealed microcalcifications in 21 cases, masses identified by ultrasonography in six cases, and mammographically identified masses and/or architectural distortion in eight cases. The masses detected by ultrasonography revealed two invasive carcinomas on excisional biopsy, two cases of lobular carcinoma in situ involving a fibroadenoma on excisional biopsy, and lobular carcinoma in situ involving adenosis in one case on excision. (One patient with an ultrasonographically detected mass identified as lobular carcinoma in situ by core needle biopsy sought excisional biopsy elsewhere.) The mammographically identified masses yielded invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy in four cases, lobular carcinoma in situ involving a radial scar on excisional biopsy in one case, and lobular carcinoma in situ involving adenosis on excisional biopsy in one case. One patient with a mammographically detected mass sought excisional biopsy elsewhere, and one has chosen to be followed clinically with no evidence of disease progression after 22 months.

Pathology

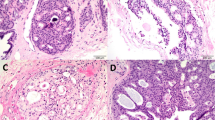

Two thousand three hundred thirty-seven breast core needle biopsies were performed at our institution as a result of an indeterminate or suspicious clinical, mammographic, or ultrasound finding between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2001. Thirty-five (1.5%) of the core biopsies had lobular carcinoma in situ (14), atypical lobular hyperplasia (17), or lobular neoplasia (4) as their most significant histologic diagnoses (Figs. 1, 2 and 3; Table 1). This represents 29 stereotactic and 6 ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy. Of the lesions examined, 51% had pagetoid extension of the atypical lobular proliferation into adjacent nonneoplastic ducts. On average, approximately 40% of the cores were involved by the lobular proliferation (range, 5 to 100%). Thirty-four percent of the lobular proliferations had histological evidence of microcalcifications within the neoplastic proliferation; 29% had associated microcalcifications in adjacent columnar alterations with prominent apical snouts and secretions (11). (Table 2) Correlation of the histological findings with the radiographic abnormalities confirmed correct identification of the targeted lesions in all cases.

Excisional biopsy was performed in 17 cases (49%). The median time to excisional biopsy was 4 weeks (range, 2 to 52 weeks). Six cases diagnosed as in situ lesions by core needle biopsy had invasive carcinoma on excision (Fig. 4). These cases included five with masses detected by ultrasound and/or mammography and one with a synchronous mass lesion (Table 3). Histologic review of the core needle biopsy in these six cases revealed that three had atypical lobular hyperplasia and pagetoid extension, one atypical lobular hyperplasia, and two had lobular carcinoma in situ with pagetoid extension.

Pagetoid spread of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ was identified in 17 of 35 cases (49%). In five of the six patients who had invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy, pagetoid extension was noted on core needle biopsy. Comparatively, twelve patients who had similar or less significant pathology on excisional biopsy also had pagetoid extension of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy. In two of six cases (33%) with invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy, histologically confirmed calcifications were identified within the in situ lesion on core needle biopsy.

In 11 cases, the excisional biopsies and core needle biopsies showed similar histology: this subset includes 3 cases of lobular carcinoma in situ involving adenosis (2 of which formed a mass lesion), 1 case of lobular carcinoma in situ involving a radial scar; the remainder were 2 cases of lobular carcinoma in situ alone, 3 cases of atypical lobular hyperplasia, and 2 cases of lobular neoplasia (Table 4). In biopsies obtained for examination of microcalcifications, microcalcifications were identified within the neoplastic acini in 20% of the cases. Eighteen patients who did not receive excisional biopsies have been followed with serial mammograms and biannual surveillance for a length of time ranging from 6 to 39 months without evidence of disease progression.

DISCUSSION

In 1941, Foote and Stewart (2) described the Memorial Hospital experience with lobular carcinoma in situ. In this sentinel paper, the authors described transformation of lobules filled with noncohesive, uniform cells. Foote and Stewart emphasized that the lesion occurred in multiple acini and was clinically and grossly unrecognizable. Additionally, the authors observed that the associated invasive carcinoma could be ductal or lobular, and thus they recommended simple mastectomy (2).

In 1966, Snyder (12) described the mammographic findings of 10 women who had biopsies that resulted in diagnoses of lobular carcinoma in situ. Punctate linear calcifications were the most common mammographic finding. In 1969, Hutter et al. (13) attempted to create a clinical and pathologic correlation with mammographic findings in lobular carcinoma in situ. The patients previously reported by Synder (12) were added to 34 new patients with the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ (13). The authors showed that mammographically detected finely stippled clusters of calcifications were often associated with lobular carcinoma in situ. Similar to the results of Snyder (12), the authors conceded that these mammographic findings were not specific for lobular carcinoma in situ and could be seen in patients with benign breast disease. Pope et al. (14) reviewed the clinical and mammographical features of 26 patients with biopsy-proven lobular carcinoma in situ not associated with any other abnormalities. In contrast to earlier studies, those investigators concluded that not only were there no specific radiologic findings for lobular carcinoma in situ but that the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ in a biopsy obtained for calcifications was probably an incidental finding (14).

Haagensen et al. (5) identified 211 examples of lobular proliferations occurring without concurrent invasion and introduced the term lobular neoplasia to encompass the spectrum of lobular disease ranging from partial lobular involvement of acini to massive acinar distension. The authors favored the terminology lobular neoplasia because it was thought that the appellative carcinoma should not be affixed to a benign disease entity. However, 17.1% of their patients diagnosed with lobular neoplasia and followed for a mean of 14 years eventually developed carcinoma (both invasive ductal carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ). The authors' recommendation for treatment was follow-up with a clinical exam every 4 months instead of mastectomy, which was the recommendation at the time (5).

In our study, classic lobular carcinoma in situ was characterized by a solid proliferation of cells with small, uniform, round-to-oval nuclei and minimal nuclear atypia. The cells were evenly spaced, with distinct cell borders, and showed loss of cohesion. Mitoses were uncommon and, by design, necrosis was not a feature of cases included in this study. Cells remained within the terminal duct lobular unit or involved adjacent ducts by pagetoid spread. We used the term atypical lobular hyperplasia to describe lesions composed of an identical cell population that had some but not all of the features of lobular carcinoma in situ. That is, residual lumens persisted in up to 50–75% of the lobule, and the acini were minimally distended and distorted (7, 8). We used the term lobular neoplasia only for the few cases in which the lobular proliferation involved a preexisting lesion and we could not quantify the amount of lobular involvement or where there was partial involvement of a terminal duct lobular unit that did not quantitatively fit exactly into the category of either lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical lobular hyperplasia.

The findings of lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy have been studied by several groups (Tables 5 and 6), and yet there are no well-defined treatment recommendations. Liberman et al. (15) reported 14 lesions diagnosed as lobular carcinoma in situ by percutaneous biopsy in which excisional biopsy material was available for review (15). In 5 of their cases, lobular carcinoma in situ was not associated with a higher risk lesion nor had overlapping features of ductal carcinoma in situ. Excisional biopsy of those five cases did not reveal either ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma histology. Additionally, Liberman et al. (15) reported the findings of four cases diagnosed as atypical lobular hyperplasia by core needle biopsy that were excised. On excision all four lesions were shown to be benign or lobular carcinoma in situ. Liberman and colleagues (15) concluded, and our findings support, that lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsy without a high-risk lesion or mammographic and/or histologic discordance does not necessarily require surgical excision.

Lechner et al. (16) performed a multi-institutional study of lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy and found that of the 58 cases that were diagnosed as lobular carcinoma in situ by core needle biopsy, 20% had invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy and 14% had ductal carcinoma in situ. Similarly, of the 84 patients with atypical lobular hyperplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsy, 6% had invasive carcinoma on excision and 15% had ductal carcinoma in situ. Unfortunately, the results are only presented in abstract form and there was no mention of histopathologic slide review or radiologic review of the cases. Lechner and colleagues (16) concluded that excisional biopsy needs to be performed on selected cases of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ; but criteria for excision were not specified.

Philpotts et al. (17) evaluated four cases of pure lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed by core needle biopsy, which represented two mammographically detected masses and two patients with calcifications. Excisional biopsy of these cases revealed one case of lobular carcinoma in situ admixed with ductal carcinoma in situ and associated with a mass lesion, two cases of lobular carcinoma in situ, and one case of atypical lobular hyperplasia. Although those investigators concluded that removal of all lobular carcinoma in situ may be prudent, if they had recommended excision of all mass lesions, than the one case of lobular carcinoma in situ with coexisting ductal carcinoma in situ would have been excised.

O'Driscoll and colleagues (4) identified seven patients with lobular carcinoma in situ as the most significant pathologic diagnosis on core needle biopsy. On excision, one case was lobular carcinoma in situ with invasive lobular carcinoma, two cases were lobular carcinoma in situ and ductal carcinoma in situ, one case was lobular carcinoma in situ with a radial scar, and three cases were lobular carcinoma in situ only. Again, we see that their single case of lobular carcinoma in situ with invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy had an associate spiculated opacity and the two cases of lobular carcinoma in situ with ductal carcinoma in situ had “indeterminate calcifications” on radiography. Notwithstanding, the authors' final recommendation was that excisional biopsy be performed on all patients with lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy.

In 2001, two studies were published describing the findings of lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy and subsequent excision. Both studies had different recommendations for the patient. Berg et al. (18) identified 15 examples of atypical lobular hyperplasia and 10 examples of lobular carcinoma in situ among 1400 consecutive core needle biopsies. Five were masses, and 20 were associated with mammographically detected microcalcifications. Seven of the patients with atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy went to excision. Six of the 7 had associated microcalcifications and showed atypical lobular hyperplasia (4), fibrocystic changes (1), and ductal carcinoma in situ (1) on excision. The 1 patient with ductal carcinoma in situ on excisional biopsy had synchronous ductal carcinoma in situ in the ipsilateral breast. One of the 7 patients with atypical lobular hyperplasia had an associated mass lesion that on excision revealed atypical lobular hyperplasia with associated fibrosis. Eight of the 10 lesions diagnosed as lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy were excised. Of those 8, 5 had calcifications on mammograms and yielded atypical ductal hyperplasia (3), lobular carcinoma in situ (1), and atypical lobular hyperplasia (1) on excision. The extent of the calcifications identified by mammography were not described. Three patients had masses associated with lobular carcinoma in situ and were diagnosed with lobular carcinoma in situ on excisional biopsy. Berg and colleagues (18) concluded that excisional biopsy should be recommended when residual calcifications remain after a diagnosis of lobular neoplasia by core needle biopsy.

Also in 2001, Pacelli et al. (19) described the Mayo Clinic's experience with lobular carcinoma in situ on core needle biopsy: seven cases of atypical lobular hyperplasia and seven of lobular carcinoma in situ that went to excisional biopsy among 3401 consecutive core needle biopsies were identified. None of the 14 patients had invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy. In addition, Pacelli and coworkers (19) studied five patients with carcinoma in situ with ductal and lobular features on core needle biopsy that went to excisional biopsy. Three of the five (60%) had invasive carcinoma on excision. Pacelli et al. (19) concluded that although carcinoma in situ with ductal and lobular features should be excised, core needle biopsy can reliably predict the pathologic findings at surgical excision for atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ.

Shin and Rosen (20) recommended that excisional biopsy may be indicated when the diagnosis of lobular carcinoma in situ is made on core needle biopsy, as 21% of patients in their series with lobular carcinoma in situ had a more significant lesion on excisional biopsy (20). In review of 20 cases with lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy and their subsequent excisional biopsies, Shin and Rosen identified a subset of eight patients with lobular carcinoma in situ as the most significant histologic abnormality. Four of the patients had lobular carcinoma in situ on excision, two had combined atypical lobular hyperplasia and atypical ductal hyperplasia on excision, and two of the patients had carcinoma on excision (one invasive ductal carcinoma and one ductal carcinoma in situ). Unfortunately, radiographic correlation was not included in the analysis. Of the five cases that were reported with atypical lobular hyperplasia on core needle biopsy as the most significant diagnosis, none had invasive carcinoma on excision. The recommendation for excisional biopsy in all cases of lobular carcinoma in situ was repeated by Hoda and Rosen (21) in a recent review outlining practice guidelines in diagnosing breast core needle biopsies.

Herein we present 17 examples of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular neoplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsy with subsequent excisional biopsy. In six of the cases in our current series (four diagnosed as atypical lobular hyperplasia and two as lobular carcinoma in situ) excisional biopsy revealed invasive carcinoma. All the patients who had invasive carcinoma on excision had masses on mammographic review (in 1 case the mass was identified retrospectively). In 5 of the 6 cases, a mass lesion was targeted and sampled. In 1 case, the patient had a synchronous mass lesion and the targeted lesion and the mass lesion was excised; multifocal invasive lobular carcinoma was identified. We therefore believe that the most important predictor of invasive carcinoma on excision of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, or lobular neoplasia is a radiographically identified synchronous mass lesion. Often this lesion is best visualized by ultrasound examination. Additionally, we identified microcalcifications within the lobules of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and lobular neoplasia 34% of the time. Lesions targeted for microcalcifications yielded microcalcifications associated with lobular carcinoma in situ histologically in 20% of the cases. On the basis of these findings, we recommend excisional biopsy lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, or lobular neoplasia only when it is associated with a synchronous mass lesion or area of architectural distortion. Our recommendation is to excise both the area of lobular carcinoma in situ proven by core biopsy and any mass lesion that may be present. Admittedly, by these criteria, a few cases of lobular carcinoma in situ involving fibroadenomas and lobular carcinoma in situ involving adenosis will be unnecessarily excised, but it is best to err on the side of caution when evaluating a mass lesion with an atypical lobular histology. Authors who have examined pure examples of lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia and have correlated mammographic and clinical findings (4, 15, 17, 22) have had similar findings. Again, we emphasize that cases of pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ with necrosis were specifically excluded from this study as we routinely recommend excision for these lobular carcinoma in situ variants.

It is important for pathologists to recognize that lobular carcinoma in situ, and occasionally atypical lobular hyperplasia, can present as a targeted lesion on core needle biopsy and that when microcalcifications are targeted on imaging, lobular carcinoma in situ or atypical lobular hyperplasia with associated microcalcifications may be seen. Interestingly columnar alterations with prominent snouts and secretions were identified in 29% of the cases of lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular neoplasia. The significance of this relationship is yet to be determined. Similar to the findings of Liberman et al. (15), 40% of the patients in our series had synchronous or metachronous carcinoma in the contralateral breast. All women diagnosed with lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular neoplasia are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer in both the ipsilateral and contralateral breast. However, none of the women in our series who had invasive carcinoma on excisional biopsy had bilateral cancer. At our institution, women with high-risk lesions are referred to the chemoprevention clinic for counseling, surveillance, and discussion of treatment options.

Interestingly, our series contained slightly more postmenopausal than premenopausal women with lobular carcinoma in situ, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and lobular neoplasia. This finding is contrary to published reports of lobular carcinoma in situ occurring more often in younger women (7, 8) and may reflect our screening population at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

This study reports our recent clinical experience with lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed by core needle biopsy. Our practice is somewhat unique in that we work closely with dedicated breast radiologists, oncologists, and surgeons. Although we only have up to 39 months of follow-up for our patients treated with surveillance, we have only noted disease progression on imaging studies (both by ultrasound and mammography) in one patient after 6 months. Our findings on excisional biopsy material suggest that lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed by core needle biopsy for calcifications and without an associated mass lesion or area of architectural distortion may be followed with biannual surveillance and chemopreventive agents. Additionally, ultrasound can assist in the evaluation of lesions classified as lobular on core needle biopsy to see if a lesion is present that is not mammographically detectable.

References

Tabor L, Vitak B, Chen HH, et al. Beyond randomized controlled trials: organized mammographic screening substantially reduces breast carcinoma mortality. Cancer 2001; 91: 1724–1731.

Foote FW, Stewart FW . Lobular carcinoma in situ. A rare form of mammary cancer. Am J Pathol 1941; 17: 491–495.

Page DL, Kidd TE Jr, Dupont WD, et al. Lobular neoplasia of the breast: higher risk for subsequent invasive cancer predicted by more extensive disease. Hum Pathol 1991; 22: 1232–1239.

O'Driscoll D, Britton P, Bobrow L, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ on core biopsy—what is the clinical significance? Clin Radiol 2001; 56: 216–220.

Haagensen CD, Lane N, Lattes R, et al. Lobular neoplasia (so-called lobular carcinoma in situ) of the breast. Cancer 1978; 42: 737–769.

Marshall LM, Hunter DJ, Connolly JL, et al. Risk of breast cancer associated with atypical hyperplasia of lobular and ductal types. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997; 6: 297–301.

Rosen PP, Kosloff C, Lieberman PH, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: detailed analysis of 99 patients with average follow-up of 24 years. Am J Surg Pathol 1978; 2: 225–251.

Page DL, Anderson TJ, Rogers LN . Lobular carcinoma in situ. In: Page DL, Anderson TJ, editors. Diagnostic histopathology of the breast. New York: Churchill Livingston, 1987: 174–182.

Fisher B, Constantino JP, Wickerman DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 1371–1388.

Bassett L, Winchester DP, Caplan RB, et al. Stereotactic core needle biopsy of the breast: a report of the Joint Task Force of the American College of Radiology, American College of Surgeons, and College of American Pathologists. CA Cancer J Clin 1997; 47: 171–190.

Fraser JL, Raza S, Chorny, et al. Columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1521–1527.

Snyder RE . Mammography and lobular carcinoma in situ. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1966; 22: 225–260.

Hutter RVP, Snyder RE, Lucas JC, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation with mammographic findings in lobular carcinoma in situ. Cancer 1969; 24: 826–839.

Pope TL, Fechner RE, Wilhelm MC, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast: mammographic features. Radiology 1988; 168: 63–66.

Liberman L, Sama M, Susnik B, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ at percutaneous breast biopsy: surgical biopsy findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173: 291–299.

Lechner MC, Jackman RJ, Brem RF, et al. Lobular carcinoma in situ and atypical lobular hyperplasia at percutaneous biopsy with surgical correlation: a multi-institutional study. Radiology 1999; 213(P): 106.

Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS, et al. Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance. Radiology 2000; 216: 831–883.

Berg WA, Mrose HE, Ioffe OB . Atypical lobular hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ at core-needle breast biopsy. Radiology 2001; 218: 503–509.

Pacelli A, Rhodes DJ, Amrami KK, et al. Outcome of atypical lobular hyperplasia and lobular carcinoma in situ diagnosed by core needle biopsy: clinical and surgical follow-up of 30 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 2001; 116: 591–592.

Shin SJ, Rosen PP . Excisional biopsy should be performed if lobular carcinoma in situ is seen on needle core biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126: 697–701.

Hoda SA, Rosen PP . Practical considerations in the pathologic diagnosis of needle core biopsies of breast. Am J Clin Pathol 2002; 118: 101–108.

Renshaw AE, Cartagena N, Derhagopian RP . Lobular neoplasia in breast core needle biopsy specimens is not associated with an increased risk of ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2002; 117: 797–799.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Leslie E. Nesbitt, our Breast Database Coordinator, and Theresa A. Guthrie, our Breast Administrative Assistant, for their assistance with the collection and preparation of the materials presented here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented at the 91st Annual United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology Meeting, February 2002, Chicago, IL.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Middleton, L., Grant, S., Stephens, T. et al. Lobular Carcinoma In Situ Diagnosed By Core Needle Biopsy: When Should It Be Excised?. Mod Pathol 16, 120–129 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000051930.68104.92

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000051930.68104.92

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Non-classic LCIS Versus Classic LCIS Versus Atypical Hyperplasia: Should Management be the Same?

Current Surgery Reports (2018)

-

Current Management of High-Risk Breast Lesions

Current Radiology Reports (2018)

-

How Do We Approach Benign Proliferative Lesions?

Current Oncology Reports (2018)

-

Upgrade rates of high-risk breast lesions diagnosed on core needle biopsy: a single-institution experience and literature review

Modern Pathology (2016)

-

Management of flat epithelial atypia on breast core biopsy may be individualized based on correlation with imaging studies

Modern Pathology (2015)