Abstract

We present a unique case of biopsy-proven necrotizing sarcoidosis involving the central nervous system (CNS) in a 52-year-old woman. The patient presented with a 3-month history of left-sided headache and sharp, shooting pains on the left side of her face. She also has a previous history of sarcoidosis, histopathologically confirmed on parotid gland biopsy 24 years before. Imaging studies of the present lesion revealed a 1.8 × 1.4-cm mass in the left temporal lobe with signal intensity suggestive of meningioma or low-grade glial neoplasm. Surgical resection was initiated, and intraoperative consultation with frozen sections revealed granulomata. The lesion was biopsied, and surgical intervention was terminated. Permanent sections failed to reveal bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, or foreign bodies. A diagnosis of necrotizing neurosarcoidosis was rendered. The patient was administered steroid therapy and clinically responded favorably. At the most recent follow-up almost 2 years later, there was no evidence of recurrence or progression. Necrotizing sarcoidosis has been reported most commonly in the lungs and rarely in other organ systems. We report the first histologically proven case involving the CNS as well as a rare example of sarcoidosis and necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis in the same patient. Sarcoidosis and its necrotizing variant should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a granulomatous mass lesion involving the CNS, particularly in the context of a history of systemic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is an idiopathic, systemic, inflammatory disorder with a predilection for middle-aged, black women. The clinical course is characterized by episodic exacerbations that are self-limited and may or may not respond to immunosuppressive therapy. Classically, the lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes are involved, although there often is variable involvement of other organ systems. Pathologic diagnosis relies heavily on the exclusion of other causes of non-necrotizing granulomata.

Sarcoidosis involving the central nervous system (CNS; neurosarcoidosis) affects only approximately 5% of patients with systemic sarcoid (1). It has been reported to involve all parts of the CNS, and its coverings including supratentorial and infratentorial compartments as well as the eye and the pituitary (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The most common presenting symptom of CNS involvement is unilateral facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) palsy (8). Imaging studies are nonspecific, revealing a poorly defined mass with a variable degree of surrounding edema. Thus, in the appropriate clinical setting, neurosarcoid should be included in the differential diagnosis of a CNS mass. A single case (7) of CNS involvement has also been reported in the absence of a classical clinical history of previous or synchronous pulmonary involvement.

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis (NSG), initially described by Liebow in 1973 (9), has been described even less frequently than its non-necrotizing counterpart. Since that initial report, approximately 115 cases involving a variety of sites, both with and without histologic confirmation, have been reported in the English language literature. The vast majority involve the lungs (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15), with some cases involving skin and subcutaneous tissues (16), kidney (17), lacrimal gland and gastrointestinal tract (18), orbit (19), liver (20), and spinal column (21). A single report (22) described neurologic involvement and CNS lesions by imaging studies in a patient with biopsy-proven pulmonary and mediastinal disease. Thus, to our knowledge, we report with histologic confirmation the first case of NSG involving the intracranial compartment reported in the English literature.

CASE REPORT

Clinical History

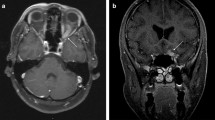

A 52-year-old woman had received a diagnosis sarcoidosis 24 years before this admission upon biopsy of a right parotid gland mass. At that time, she also had suspicious lesions in the lungs as well as hilar lymphadenopathy. During the next 24 years, additional granulomatous lesions were identified in biopsies of the skin and lungs. Skin tests at that time were negative for mumps, tuberculosis (PPD), histoplasmosis, and coccidiomycosis. Other pertinent history includes smoking and sinusitis. Family history is noncontributory. On this admission, the patient presented with a 3-month history of new-onset left-sided headache and shooting pain on the left side of her face. Neurologic examination was significant for hyperesthesias on the left side of the face in the territory of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Computerized tomography revealed a 1.8 × 1.4-cm mass in the left temporal lobe and cavernous sinus area. The mass was isointense and revealed mild surrounding edema. Magnetic resonance neuroimaging studies, with and without contrast, identified a lesion with signal intensities suggestive of meningioma or glial neoplasm (Fig. 1). Increased T2 signal was also seen, suggesting compression of adjacent tissue. Administration of gadolinium resulted in significant enhancement that seemed fairly homogeneous. An incidental right ethmoid mucocele was also noted. Chest x-ray showed no lung lesions, and no lymphadenopathy was detected in the mediastinum. The patient underwent a left subtemporal craniotomy with partial resection of the mass, at which time intraoperative frozen-section diagnosis revealed an inflammatory, granulomatous process. After additional biopsies for further histopathologic examination, the surgical procedure was terminated.

Neuroimaging studies revealing a homogeneously enhancing lesion with a dural attachment involving the left temporal lobe and extending into the cavernous sinus. A, axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image after intravenous gadolinium. B, coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image after intravenous gadolinium.

Histopathology

Routinely processed sections revealed neuroglial tissue heavily involved with multiple granulomas. Large and small multinucleated giant cells were distributed in the immediate vicinity of these granulomatous areas as well as in adjacent tissue devoid of necrotic foci (Fig. 2A). These lesions consisted of focal areas of coagulative necrosis, surrounded by a rim of mononuclear cells (Fig. 2B). The latter often had either oval-shaped or elongated irregular and indented nuclei. Most cells also had a generous amount of pink cytoplasm. Intermixed with the epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells were a modest number of lymphocytes and plasma cells, although acute inflammatory infiltrates including segmented neutrophils or eosinophils were not seen (Fig. 2C). There was no definitive vasculitis, although some vessels had inflammatory cells around them. Sections were stained with Gomori methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff and did not reveal any fungal organisms. Multiple stains for mycobacteria/acid-fast organisms were negative. These included Zeihl-Neilsen and modified acid-fast (Fite’s), as well as auramine-rhodamine fluorescent stain. Cultures obtained intraoperatively failed to grow any organisms. No foreign body was identified by examination with polarized light. The patient’s previous parotid gland mass biopsy from 24 years before was reexamined. The histopathology was typical non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Histochemical stains performed previously on that specimen had also failed to reveal any organisms, and a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was reconfirmed. In view of the patient’s history and diagnosis of sarcoidosis as well as the prior favorable response to steroids, the present biopsy with necrotizing granulomatosis and lack of infectious cause was diagnosed as NSG. The patient’s clinical condition has significantly improved with steroid therapy; almost 2 years later, there is no evidence, clinical or radiographic, of recurrence or progression of the mass.

A, a hypercellular inflammatory process infiltrating neuroglial tissue. A small area of necrosis is present in the center (arrowhead). Randomly distributed in the vicinity are a large number of mononuclear cells and multiple small and large multinucleated giant cells (arrows). B, a granuloma with a central region of coagulative necrosis including “ghost forms” is illustrated. Palisading around the necrotic focus are mononuclear and occasional multinucleated cells. Chronic inflammatory cells (i.e., lymphocytes and plasma cells) are also noted. C, at higher magnification, the nuclei of the mononuclear cells seen around the necrotic focus are frequently elongated, irregular, or indented. The nuclei within the multinucleated cells are often arranged around the periphery (arrow) but in many instances were randomly clustered within the cytoplasm. Although some nuclear debris is present, acute inflammatory cells are conspicuously absent.

DISCUSSION

We report the first histologically confirmed case of intracranial NSG. Necrotizing sarcoidosis differs from typical sarcoidosis by the presence of significant noncaseating necrosis and confluent granulomatous inflammation consisting of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, usually with an associated granulomatous vasculitis (11, 12, 18). The differential diagnosis of necrotizing granulomas includes chronic infections such as typical and atypical mycobacterium, fungi (e.g., histoplasmosis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis), and Wegener’s granulomatosis, as well as foreign body type granulomatous inflammations. Therefore, a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, necrotizing or non-necrotizing, should be made only after other causes of granulomas have been excluded. Mycobacterial and fungal causes can be excluded by various histochemical stains and ideally by culture. Wegener’s granulomatosis frequently has a characteristic clinical presentation in terms of both the clinical course and the distribution of lesions. Increased serum c-ANCA levels may further support it. Histologically, the granulomatous inflammatory process has a significant acute inflammatory component, accompanied by a large number of segmented neutrophils and a necrotizing vasculitis. The necrosis of Wegener’s also often creates geographic patterns and may be surrounded by palisading histiocytes. NSG patients typically have a long clinical course with a significant, favorable response to steroids. These features clearly rule out infectious causes, particularly when supported by negative cultures.

A brief summary of reports of NSG in the scientific literature is presented in Table 1. A total of 116 cases were identified, with 62 histologically confirmed cases including the present report. The average age was 42 years (range, 11 to 66 years). Not surprising is that many patients had been treated for infectious causes, usually mycobacterial infections. Treatment with steroids typically followed identification of the cause, and the clinical response was often favorable.

The relationship between sarcoidosis and NSG remains poorly defined. Churg et al. (10) in their report describing 12 cases of NSG suggested that this entity is most likely a variant of typical sarcoidosis or is closely related. The histologic features and the clinical course of the disease, although different enough to merit its own designation, bears sufficient similarities to sarcoidosis to be classified in the same group of disorders. The authors also described in the same report (10) a patient with pulmonary NSG and uveitis who also had noncaseating granulomas in her hilar lymph nodes. The present case provides another example of classic non-necrotizing sarcoid, previously diagnosed on biopsies, followed by NSG. This lends additional support to the contention that NSG may indeed be a variant of sarcoidosis.

Our case report illustrates the importance of including inflammatory disorders such as sarcoidosis in the differential diagnosis of a CNS mass in a patient with appropriate clinical presentation. History of systemic sarcoidosis should raise further suspicions regarding the cause of any intracranial lesion. Intracranial involvement by sarcoidosis without previous clinical history, although extremely rare, has been reported (2, 4, 7). There are no specific imaging or laboratory findings for neurosarcoidosis and therefore a high level of clinical suspicion must be maintained and appropriate tests to rule out other causes must be performed.

The present report also emphasizes the need to keep neurosarcoidosis, rather than other infectious causes, on the list of differential diagnoses to be considered for necrotizing granulomas in the brain. Necrotizing sarcoidosis, like typical sarcoidosis, is a diagnosis of exclusion and should not be made until all special studies including cultures have been performed to rule out an infectious cause. Although patients with confirmed extrapulmonary necrotizing sarcoidosis and a single case with presumed CNS involvement have been described in the literature (22), this report is the first to document histologically proven intracranial involvement. It also provides a rare example of the combined presentation of a case with typical sarcoidosis and subsequent necrotizing granulomatosis.

References

Scott, TF . Neurosarcoidosis: progress and clinical aspects. Neurology 1993;43:8–12.

Levivier M, Brotchi J, Baleriaux D, Pirotte B, Flament-Durand J . Sarcoidosis presenting as an isolated intramedullary tumor. Neurosurgery 1991;29:271–276.

Graf M, Wakhloo A, Schmidtke K, Bloss H, Volk B . Sarcoidosis of the spinal cord and medulla oblongata. A pathological and neuroradiological case report. Clin Neuropathol 1994;13:19–25.

Stelzer KJ, Thomas CR, Berger MS, Spence AM, Shaw C, Griffin TW . Radiation therapy for sarcoid of the thalamus/posterior third ventricle: case report. Neurosurgery 1995;36:1188–1191.

Maisel JA, Lynam T . Unexpected sudden death in a young pregnant woman: unusual presentation of neurosarcoidosis. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:94–97.

Jallo GI, Zagzag D, Lee M, Deletis V, Morota N, Epstein FJ . Intraspinal sarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Surg Neurol 1997;48:514–520.

Jackson RJ, Goodman JC, Huston DP, Harper RL . Parafalcine and bilateral convexity neurosarcoidosis mimicking meningioma: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1998;42:635–638.

Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA . Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1224–1233.

Liebow AA . Pulmonary angiitis and granulomatosis. Am Rev Resp Dis 1973;108:1–18.

Churg A, Carrington CB, Gupta R . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis. Chest 1979;76:406–413.

Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Feigin DS, Garancis JC, Ward PA . Necrotizing sarcoid-like granulomatosis: clinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic findings. Hum Pathol 1980;11:510–519.

Rolfes DB, Weiss MA, Sanders MA . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with suppurative features. Am J Clin Pathol 1984;82:602–607.

Chittock DR, Joseph MG, Paterson NAM, McFadden RG . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with pleural involvement. Chest 1994;106:672–676.

Niimi H, Hartman TE, Muller NL . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis computed tomography and pathologic findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1995;19:920–923.

Hsu RM, Connors AF, Tomashefski JF . Histologic, microbiologic and clinical correlates of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis by transbronchial biopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120:364–368.

Kuramoto Y, Shindo Y, Tagami H . Subcutaneous sarcoidosis with extensive caseation necrosis. J Cutan Pathol 1988;15:188–190.

Ito Y, Suzuki T, Mizuno M, Morita Y, Muto E, Ichida S, et al. A case of renal sarcoidosis showing central necrosis and abnormal expression of angiotensin converting enzyme in the granuloma. Clin Nephrol 1994;42:331–336.

LeGall F, Loeuillet L, Delaval P, Thoreux PH, Desrues B, Ramee MP . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with and without extrapulmonary involvement. Pathol Res Pract 1996;192:306–313.

Dykhuizen RS, Smith CC, Kennedy MM, McLay KA, Cockburn JS, Kerr KM . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with extrapulmonary involvement. Eur Respir J 1997;10:245–247.

Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Epstein MS, Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG . Hepatic sarcoidosis clinicopathologic features in 100 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:1272–1280.

Singh N, Cole S, Krause PJ, Conway M, Garcia L . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with extrapulmonary involvement. Am Rev Resp Dis 1981;124:189–192.

Beach RC, Corrin B, Scopes JW, Graham E . Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with neurologic lesions in a child. J Pediatr 1980;97:950–953.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strickland-Marmol, L., Fessler, R. & Rojiani, A. Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis Mimicking an Intracranial Neoplasm: Clinicopathologic Features and Review of the Literature. Mod Pathol 13, 909–913 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880162

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880162

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ocular sarcoidosis in adults and children: update on clinical manifestation and diagnosis

Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2023)

-

Spontaneous necrotizing granuloma of the cerebellum: a case report

BMC Neurology (2020)

-

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with hemoptysis: a case report and literature review

Diagnostic Pathology (2013)

-

The challenge of profound hypoglycorrhachia: two cases of sarcoidosis and review of the literature

Clinical Rheumatology (2011)

-

Tuberculous meningoencephalitis in a pregnant woman presenting 7 years after removal of a cerebral granuloma

European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (2008)