Abstract

We present the histopathologic features of fatal Burkholderia cepacia pneumonia in three adults (one man [age 44 years] and two women [aged 40 and 43 years]). In all patients, the pulmonary infiltrates initially were localized (right middle lobe, left upper lobe, and right middle lobe) but rapidly progressed. Two open-lung biopsies and one pneumonectomy specimen showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation merging with areas of more conventional necrotizing bronchopneumonia. In one patient, a mediastinal lymph node also showed stellate necrotizing granulomas. Vasculitis was absent. B. cepacia was cultured from the open-lung biopsies and bronchial wash specimens in two patients and from postmortem cultures of lung, subcarinal lymph nodes, and blood in the third. The histopathology in these patients resembles that of melioidosis, which is caused by a related organism, Burkholderia pseudomallei. B. cepacia needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. In addition, given the rarity with which B. cepacia is identified as a cause of pneumonia in the immunocompetent host, isolation of B. cepacia should trigger a workup for underlying immunodeficiency or lead to an investigation to exclude the possibility of a nosocomial infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia cepacia is a ubiquitous organism that rarely causes infection in the immunocompetent host. Recently, much attention has been drawn to its role as a pathogen in patients who have cystic fibrosis (CF), in whom its isolation has been associated with rapid clinical deterioration (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). It is also gaining recognition as a pathogen in nosocomial infections (7) and in patients who are immunodeficient, particularly those who have chronic granulomatous disease (1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). Detailed descriptions of the histopathology of B. cepacia pneumonia are lacking. We present the histologic features found in three adults who did not have CF and who developed progressive pneumonia as a result of B. cepacia infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Slides from three open-lung biopsy specimens and one pneumonectomy specimen from three adults were received in consultation by one of us (TC). Acid-fast, Gomori’s methenamine silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were either negative upon review or reported as negative by the referring pathologist. Acid fast, Gomori’s methenamine silver, Brown-Brenn, and Warthin-Starry stains performed by us on the pneumonectomy specimen from Patient 2 were also negative for organisms. The autopsy report of Patient 1 was also reviewed.

RESULTS

The clinical histories for each of these patients are spotty and are summarized in Table 1. All three patients were middle-aged adults (one man [age 44 years] and two women [aged 40 and 43 years]) who presented with symptoms that were consistent with community-acquired pneumonia. The patients were from different geographic regions of the United States. Patient 2 had a 15 pack-year smoking history, Patient 3 did not smoke, and the smoking history of Patient 1 is unknown. In all three patients, the pulmonary infiltrates initially were localized (right middle lobe, left upper lobe, and right middle lobe respectively) but rapidly progressed despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Bronchoscopic biopsies were nondiagnostic, and open-lung biopsies were performed. In Patients 2 and 3, the open-lung biopsies and the bronchial washings/brushings grew B. cepacia. In Patient 1, the lung tissue from the open biopsy did not yield an organism; at autopsy, the lung, blood, and carinal lymph nodes all grew B. cepacia.

Patient 1's medical history was significant for histoplasmosis at age 19 and a vague history of recurrent childhood infections. Patient 2 had a history of maxillary sinusitis and had been hospitalized twice at ages 34 and 35 for pneumonia. Salmonella paratyphi B was identified as the cause of the second episode of pneumonia. The patient was African American, and a hemoglobin electrophoresis performed at that time identified the AA phenotype with no evidence of hemoglobin S. Patient 3 had a 16-year history of a lupus-like syndrome and was on chloroquine at the time of her initial admission. Serologic studies were negative for antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro (SSA) antibodies, and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.

Pathologic Findings

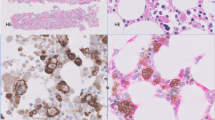

The pathologic findings are summarized in Table 2. The bronchoscopic biopsies of Patients 1 and 3 were described as consistent with pneumonia. The bronchoscopic biopsy of Patient 2 showed hyaline membranes, pulmonary edema, and intra-alveolar neutrophils, consistent with pneumonia. The open-lung biopsies and the pneumonectomy specimen were similar and showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with prominent central neutrophilic karyorrhexis (Figs. 1 and 2). Microabscesses, which were confluent in areas, were also present. The alveoli were filled with fibrin exudates containing variable numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. The alveolar septa were widened by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Necrosis was a prominent feature and was extensive and confluent in some foci. The lungs were congested, but frank hemorrhage was not present. Occasional small non-necrotizing granulomas were apparent. These were located within alveoli, and the larger granulomas exhibited central necrosis with suppuration. Non-necrotizing sarcoid-like granulomas and vasculitis outside the area of inflammation were absent. The granulomatous foci merged with areas of more conventional bronchopneumonia (Fig. 3). A mediastinal lymph node removed at the time of pneumonectomy in Patient 2 contained stellate necrotizing granulomas.

DISCUSSION

Detailed descriptions of B. cepacia pneumonia are rare. These patients present a unique opportunity to examine the histologic features in adults who do not have CF. The most striking finding was the prominent necrotizing granulomatous inflammation associated in some areas with extensive tissue necrosis. These features raised the concern of Wegener's granulomatosis to the referring pathologists. The lack of vasculitis away from the area of inflammation, the absence of background multinucleated giant cells, and the lymph node involvement in Patient 2 all argued against a diagnosis of Wegener's granulomatosis.

A review of the literature reveals two reports of the histopathology of B. cepacia pneumonia. The first is an autopsy study that compared the histopathologic features of patients who had CF and who were colonized with B. cepacia with those who were not (16). Although no histopathologic pattern was specific for any group, those who experienced a more rapid downhill course were found to have more extensive necrotizing bronchopneumonia; some showed contiguous bronchiolocentric abscesses. Bronchocentric cavities lined by an acute fibrinopurulent exudate, a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and a zone of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells were also more prevalent in this group. Dr. Tomashefski kindly shared some of the slides from the CF study illustrating the bronchiectasis with superimposed acute necrotizing bronchitis and bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia. These contrast sharply with our three patients in which necrotizing granulomas with peripheral palisading epithelioid histiocytes were an integral part of the inflammatory picture. The second is a case report of an 18-year-old man with pneumonia caused by eugonic oxidizer, an old name for B. cepacia (17). The histologic findings are similar to our patients', revealing necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.

The histologic appearance noted in these specimens is strikingly similar to the histopathology of melioidosis, which ranges from an acute suppurative pneumonia to a chronic granulomatous inflammation (18, 19). Melioidosis is caused by a related organism, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Acute melioidosis is characterized by the formation of microabscesses, which in the lung become confluent and form a necrotizing bronchopneumonia. Varying numbers of macrophages and scattered giant cells are also present. As in our patients, necrosis is a consistent and prominent feature. Chronic melioidosis is a granulomatous process, forming either necrotizing granulomas with central stellate abscesses or caseating granulomas as characterizes tuberculosis. It would not be surprising for two related organisms, B. pseudomallei and B. cepacia, to cause similar morphologic patterns.

B. cepacia, therefore, needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of necrotizing granulomatous inflammations in the lung. Early recognition may be important as in each of these patients, the course was progressive and relentless despite therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics. A review of the literature raises serious questions as to whether this organism ever occurs in immunocompetent people. Only rare cases have been reported in immunocompetent hosts (17, 20). However, its presence has been strongly associated with disorders of neutrophil function, such as chronic granulomatous disease. Neutrophilic function was not evaluated in any of these patients. Given the strong association of B. cepacia with immunologic deficiencies and its rarity as a pathogen in immunocompetent people, isolation of this organism should alert the pathologist to suspect an unrecognized immunodeficiency or a nosocomial infection with the hope of guiding clinical management.

References

Hamill RJ, Houston ED, Georghiou PR, Wright CE, Koza MA, Cadle RM, et al. An outbreak of Burkholderia (formerly Pseudomonas) cepacia respiratory tract colonization and infection associated with nebulized albuterol therapy. Annu Intern Med 1995; 122 (10): 762–766.

Tablan OC . Nosocomially acquired Pseudomonas cepacia infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1993; 14 (3): 124–126.

Taylor R, Gaya H, Hodson ME . Pseudomonas cepacia: pulmonary infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med 1993; 87: 187–192.

Taylor RF, Dalla Costa L, Kaufmann ME, Pitt TL, Hodson ME . Pseudomonas cepacia pulmonary infection in adults with cystic fibrosis: is nosocomial acquisition occurring? J Hosp Infect 1992; 21 (3): 199–204.

Webb AK . The treatment of pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1995; 96: 24–27.

Whiteford ML, Wilkinson JD, McColl JH, Conlon FM, Michie JR, Evans TJ, et al. Outcome of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia colonisation in children with cystic fibrosis following a hospital outbreak. Thorax 1995; 50 (11): 1194–1198.

Goldmann DA, Klinger JD . Pseudomonas cepacia: biology, mechanisms of virulence, epidemiology. J Pediatr 1986; 108 (5 Pt 2): 806–812.

Bottone EJ, Douglas SD, Rausen AR, Keusch GT . Association of Pseudomonas cepacia with chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Microbiol 1975; 1 (5): 425–428.

Lacy DE, Spencer DA, Goldstein A, Weller PH, Darbyshire P . Chronic granulomatous disease presenting in childhood with Pseudomonas cepacia septicaemia. J Infect 1993; 27 (3): 301–304.

O'Neil KM, Herman JH, Modlin JF, Moxon ER, Winkelstein JA . Pseudomonas cepacia: an emerging pathogen in chronic granulomatous disease. J Pediatr 1986; 108 (6): 940–942.

Schapiro BL, Newburger PE, Klempner MS, Dinauer MC . Chronic granulomatous disease presenting in a 69-year-old man. N Engl J Med 1991; 325 (25): 1786–1790.

Speert DP, Bond M, Woodman RC, Curnutte JT . Infection with Pseudomonas cepacia in chronic granulomatous disease: role of nonoxidative killing by neutrophils in host defense. J Infect Dis 1994; 170 (6): 1524–1531.

Clegg HW, Ephros M, Newburger PE . Pseudomonas cepacia pneumonia in chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Infect Dis 1986; 5 (1): 111.

Berry MD, Asmar BI . Pseudomonas cepacia bacteremia in children with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991; 10 (9): 696–699.

Pegues DA, Carson LA, Anderson RL, Norgard MJ, Argent TA, Jarvis WR, et al. Outbreak of Pseudomonas cepacia bacteremia in oncology patients. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16 (3): 407–411.

Tomashefski JF, Thomassen MJ, Bruce MC, Goldberg HI, Konstan MW, Stern RC . Pseudomonas cepacia-associated pneumonia in cystic fibrosis: relation of clinical features to histopathologic patterns of pneumonia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1988; 112 (2): 166–172.

Dailey RH, Benner EJ . Necrotizing pneumonitis due to the pseudomonad “eugonic oxidizer—group I.” N Engl J Med 1968; 279 (7): 361–362.

Piggott JA, Hochholzer L . Human melioidosis: a histopathologic study of acute and chronic melioidosis. Arch Pathol 1970; 90 (2): 101–111.

Wong KT, Puthucheary SD, Vadivelu J . The histopathology of human melioidosis. Histopathology 1995; 26 (1): 51–55.

Wong SN, Tam AY, Yung RW, Kwan EY, Tsoi NN . Pseudomonas septicaemia in apparently healthy children. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991; 80 (5): 515–520.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Belchis, D., Simpson, E. & Colby, T. Histopathologic Features of Burkholderia Cepacia Pneumonia in Patients Without Cystic Fibrosis. Mod Pathol 13, 369–372 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880060

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880060