Abstract

Eosinophilic cell change is one of the most common endometrial metaplasias occurring in both non-neoplastic and neoplastic endometrium. Its phenotypic characteristics have not still been fully clarified. We examined expression of mucin core proteins in a total of 95 distinct histological areas of endometrial specimens comprising 39 benign nonhyperplastic endometria, 14 endometrial hyperplasias, and 42 endometrial carcinomas. Eosinophilic cell change was very common, seen in 27 endometrial areas (28%); mucinous metaplasia (28%) and ciliated (tubal) change (31%), were also frequently seen. Eosinophilic cell change was more frequently seen in endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma than in benign nonhyperplastic endometrium. In endometrial carcinomas, eosinophilic cell change was frequently associated with mucinous metaplasia and the two types of metaplastic cells were occasionally intermingled in a single neoplastic gland. A total of 23 (85%) of 27 eosinophilic cell changes and 18 (72%) of 25 mucinous metaplasias showed MUC5AC expression. These frequencies of MUC5AC expression did not differ significantly among benign non-hyperplastic endometrium, endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma. Totally, 15 (52%) of 29 ciliated (tubal) changes and two (100%) of two surface syncytial changes, which showed cytoplasmic eosinophilia at least focally, also expressed MUC5AC. Most of the endometrial changes characterized by cytoplasmic eosinophilia may be subtypes of immature mucinous metaplasia which express a mucin core protein but are not fully glycosylated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Endometrial epithelial metaplasia refers to the phenomenon in which endometrial glandular epithelium is replaced by other types of cells which are either not seen or very rarely seen in normal endometrial glands. This phenomenon was first described systematically by Hendrickson and Kempson in 1980.1 Endometrial metaplastic and related changes include squamous metaplasia/morules, mucinous metaplasia, ciliated (tubal) change, eosinophilic cell change, hobnail cell change, clear cell change, secretory change, surface syncytial change, papillary proliferation, and Arias-Stella change.1, 2, 3 It is not uncommon to see several different types of metaplasia simultaneously in a single gland or even in a single cell.1, 2

When normal or hyperplastic endometrium shows metaplastic changes, there is a risk of misinterpretation as atypical hyperplasia or even carcinoma. Eosinophilic cell change was previously reported to be most frequently misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma.1 It is characterized by cytoplasmic eosinophilia. Cytoplasmic vacuolization or granularity is occasionally seen. Eosinophilic cell change and the closely related ciliated (tubal) change are seen not only in normal endometrium but also in various non-neoplastic and neoplastic endometrial lesions.4, 5 The cellular nature of eosinophilic cell change is poorly characterized, except for the rare subtype of oncocytic metaplasia, which is characterized by eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. Abundant intracytoplasmic mitochondria have been identified ultastructurally in oncocytic metaplasia of both benign and malignant endometrium.6 However, the phenotypic characteristics of most other eosinophilic cell changes have not been evaluated in large numbers of cases.

We have noted occasional cytoplasmic vacuolation and a frequent association of eosinophilic cell change with mucinous metaplasia in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Clement and Young7 described the frequent admixture of an oxyphilic cell component in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium in their recent review. We speculated that eosinophilic cell change may have some relationship to mucinous metaplasia.

In this study, we examined the expression of MUCs2, 5AC, and 6 in both normal endometrium and a variety of endometrial lesions and evaluated the relationships between eosinophilic cell change and mucinous differentiation. We did not examine MUC1 expression in the present study because MUC1 is already known to be expressed in almost any normal epithelial cells, not only in the female genital tract8 but also in many other organs.9

Materials and methods

We used formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections of endometrium from 85 cases obtained either by surgery or curettage. When one case contained more than two different lesions (ie carcinoma and endometrial polyp), the two lesions were evaluated separately, so a total of 95 distinct histological areas were the subject of this study. The age of the patients ranged from 17 to 81 years (mean 56 years). The history of hormone replacement therapy was unknown. The 95 areas consisted of 39 benign nonhyperplastic endometria (including four normal proliferative phase, four normal secretory phase, seven abnormally cycling endometria, five atrophic endometria, 11 endometrial polyps, five adenomyosis, two polypoid adenomyoma, and one atypical polypoid adenomyoma), 14 endometrial hyperplasias (including six simple nonatypical, three complex nonatypical, and five complex atypical hyperplasias), and 42 endometrial carcinomas (including 32 grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinomas, four grade 2 endometrioid adenocarcinomas, three mucinous adenocarcinomas, and three serous adenocarcinomas). In all 95 areas, we specified the presence or absence of metaplasia, and the type of metaplasia if present. In this study, carcinomas were classified as mucinous adenocarcinoma when more than 70% of the tumor was occupied by neoplastic cells with abundant cytoplasmic mucin.

For immunohistochemistry, 4 μm-thick serial sections were made from paraffin blocks. In hysterectomy cases, one or two blocks which contained the most representative lesion were selected for immunohistochemistry. The antibodies used were MUC2 (Ccp58, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1:100), MUC5AC (CLH2, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1:100), and MUC6 (CLH5, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1:100). The specimens were pretreated with citrate buffer of pH 6.0 at 121°C for 5 min. Signals were detected using LSAB2kit/HRP (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and Simple Stain DAB solution (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). χ2-test was used for statistical analyses. Differences with P-values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The frequencies of metaplastic changes are shown in Table 1. Of the 95 areas examined, 27 (28%) contained eosinophilic cell change. Eosinophilic cell change was the most common metaplasia in endometrial hyperplasia and was seen in seven (50%) of the 14 lesions. In endometrial carcinoma, mucinous metaplasia (Figure 1a) was the most common metaplasia, followed by eosinophilic cell change (Figure 1b), seen respectively in 21 (49%) and 16 (37%) of the 42 lesions. Eosinophilic cell change was more frequently seen in endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma than in benign nonhyperplastic endometrium. No metaplasia was seen in the three serous adenocarcinomas studied.

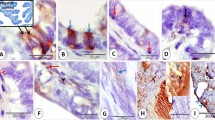

(a) Mucinous metaplasia in an endometrioid adenocarcinoma: × 40. The cells resemble those of endocervical adenocarcinoma. (b) Eosinophilic cell change in the same case: × 200. (c) Coexistence of mucinous (arrow) and eosinophilic cells (arrow head) within a single neoplasic gland: × 100. (d) MUC5AC expression in neoplastic cells: × 200.

Two or more types of metaplasia were seen in the same focus studied in 22 cases. The combination of eosinophilic cell change and mucinous metaplasia was the most common, seen in 12 lesions, all of which were endometrioid adenocarcinomas. In total, 75% of the endometrioid adenocarcinomas with eosinophilic cell change also had mucinous metaplasia. Focally, the two types of metaplastic cells were also seen simultaneously within a single neoplastic gland (Figure 1c). Eosinophilic cell change and ciliated (tubal) change were the second most common combination, and this pattern was mostly seen in benign nonhyperplastic endometrium. Ciliated (tubal) change usually showed cytoplasmic eosinophilia. Two lesions of surface syncytial change also showed cytoplasmic eosinophilia.

Expression of the mucin core proteins is shown in Table 2. In all, 44 cases, five of which were grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma containing areas of normal endometrium within the same specimen, had conventional normal endometrial glands without metaplasia. In 19 (43%) of these 44 cases, MUC6 was positive in the deeper portion of at least a few glands. MUC6-positive glands were more frequent in atrophic endometria than in nonatrophic ones. None of the glands that expressed MUC6 were of secretory type. Nonmetaplastic glands in endometrial hyperplasia did not express any core proteins. Five (14%) of the 36 endometrioid adenocarcinomas expressed MUC6 focally in the conventional endometrioid-type neoplastic glands.

Among metaplasias, expression of the mucin core proteins was noted at least focally in ciliated (tubal) change, mucinous metaplasia, eosinophilic cell change, and surface syncytial change (Table 3). Squamous metaplasia/morules and Arias-Stella change did not express any of the core proteins. MUC5AC was the most common core protein expressed. MUC2 was seen in only one case of endometrial polyp with intestinal metaplasia. This polyp also showed mucinous metaplasia mimicking pyloric glands and MUC6 was positive in those glands.

MUC5AC expression was especially characteristic of eosinophilic cell change (Figure 2) and mucinous metaplasia (Figure 1d), being positive in 24 (89%) of 27 eosinophilic cell changes and 18 (72%) of 25 mucinous metaplasias. The pattern of staining was either sporadic or diffuse. The frequency of MUC5AC expression in mucinous metaplasia and eosinophilic cell change did not differ significantly among benign nonhyperplastic endometrium, endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma. Both of the two surface syncytial and 15 (72%) of 29 ciliated (tubal) changes also showed MUC5AC expression. All these metaplastic lesions showed at least focal cytoplasmic eosinophilia.

Discussion

It is notable that not only mucinous metaplasia, but also 88% of the endometria with eosinophilic cell change, expressed MUC5AC. Interestingly, mucinous metaplasia and eosinophilic cell change frequently coexisted in the same fields and even within the same neoplastic glands in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The two types of metaplasia seem to be closely related. Eosinophilic cell change which is positive for MUC5AC may represent a more immature stage of mucinous metaplasia that expresses mucin core protein but has not been fully glycosylated. In noncancerous endometrium, the metaplastic cells may be stable; however, in endometrial carcinoma, because of the relative genetic instability, a transition between eosinophilic cell change and mucinous metaplasia may be more likely to occur.

In the normal human uterus, mucinous epithelium exists in endocervical mucosa. Phenotypic characteristics of mucinous epithelium of the endocervix have been investigated by mucin histochemistry and immunohistochemistry. According to those studies, endocervical mucinous epithelium has the same type of mucin as that of gastric foveolar epithelium.10, 11 Although the columnar epithelium of endometrial glands is characterized by the lack of cytoplasmic mucin, endocervical type mucinous epithelium can be seen in benign and neoplastic endometrium.12, 13 Primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium14 is considered to be the extreme of mucinous metaplasia in endometrioid adenocarcinoma and its clinical behavior does not differ significantly from that of conventional endometrioid adenocarcinoma.7, 15 The mucinous neoplastic epithelium in endometrioid adenocarcinoma is histochemically identical to normal endocervical mucinous epithelium.12, 13, 14

Morphologically recognizable mucins are high molecular weight glycoproteins, more than 50% of which consist of O-linked oligosaccharides.9 Mucins are made up of core proteins coded by mucin genes specific to their types and chains of numerous oligosaccharides binding to the core proteins. Epithelial mucins are classified into eight types: MUC1, MUC2, MUC3, MUC4, MUC5AC, MUC5B, MUC6 and MUC7, by the types of their core proteins.9 Monoclonal antibodies to some of these core proteins are now available commercially. Immunohistochemistry using the antibodies to these mucin core proteins can detect cells showing mucinous differentiation with higher sensitivity than mucin histochemical stains, because it can recognize the cells showing mucin gene expression but not fully glycosylated. In normal human female reproductive tract epithelia, MUCs1, 4, 5AC, 5B, and 6 were identified in uterine cervical mucosa, and MUCs1 and 6 have been identified in the endometrium.8 MUC2 was identified in immature squamous metaplasia of the uterine cervix.16 The present study using immunohistochemistry for mucin core proteins also confirmed similar mucin core protein between normal endocervical mucinous epithelium and mucinous metaplasia of both normal and pathological endometrium.

In addition to mucinous metaplasia and eosinophilic cell change, MUC5AC was also positive in 100% of surface syncytial change (although only two cases) and 52% of ciliated (tubal) change. All these lesions also showed cytoplasmic eosinophilia at least focally. Not only surface syncytial change, but also ciliated (tubal) change, frequently involved the endometrial surface epithelium. On the other hand, MUC6 was seen in deeper portions of a few endometrial glands in 43% of normal non-metaplastic endometria. The tendency of MUC6-positive glands to be more visible in atrophic endometria may reflect the relative predominance of the basalis over the functionalis in atrophic endometria.

MUC5AC and MUC6 were originally described in the stomach; the former was seen in foveolar epithelium and the latter in pyloric glands.9 The polarity of surface MUC5AC and deep MUC6 expression was reported not only in normal gastric mucosa, but also in gastric metaplasia occurring in the ileum with Crohn’s disease,17 in ulcerative colitis with regeneration,18 and in Barrett’s esophagus of experimental animals.19 The greater likelihood of MUC5AC to be expressed on the surface of the endometrium may be ascribed to regenerative reactions after various insults. There are several articles which suggest that surface syncytial change of the endometrium may represent a regenerative phenomenon.20 Eosinophilic cell change associated with surface syncytial change and ciliated (tubal) change occurring in the surface endometrium may thus also be an exaggerated form of regenerative change.

References

Hendrickson MR, Kempson RL . Endometrial epithelial metaplasias: proliferations frequently misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma. Report of 89 cases and proposed classification. Am J Surg Pathol 1980;4:525–542.

Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ . Precursor lesions of endometrial carcinoma. In: Kurman RJ (ed). Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Springer-Verlag: New York, 2002, pp 484–492.

Silverberg SG, Kurman RJ . Tumor-like lesions. In: Rosai J (ed). Tumor of the Uterine Corpus and Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, 1992, pp 191–204.

Kaku T, Silverberg SG, Tsukamoto N, et al. Association of endometrial epithelial metaplasia with endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia in Japanese and American women. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:297–300.

Mai KT, Yazdi HM, Boone SA . ‘Minimal deviation’ endometrioid carcinoma with oncocytic change of the endometrium. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995;119:751–754.

Silver SA, Cheung ANY, Tavassoli FA . Oncocytic metaplasia and carcinoma of the endometrium: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1999;18:12–19.

Clement PB, Young RH . Non-endometrioid carcinomas of the uterine corpus: a review of their pathology with emphasis on recent advances and problematic aspects. Adv Anat Pathol 2004;11:117–142.

Gipson IK, Ho SB, Spurr-Michaud SJ, et al. Mucin gene expressed by human female reproductive tract epithelia. Biol Reprod 1997;56:999–1011.

Gendler SJ, Spicer AP . Epithelial mucin genes. Annu Rev Physiol 1995;57:607–634.

Riethdorf L, O’Connell JT, Riethdorf S, et al. Differential expression of MUC2 and MUC5AC in benign and malignant glandular lesions of the cervix uteri. Virchows Arch 2000;437:365–371.

Zhao S, Hayasaka T, Osakabe M, et al. Mucin expression in nonneoplastic and neoplastic glandular epithelia of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:393–397.

Czernobilsky B, Katz Z, Lancet M, et al. Endocervical-type epithelium in endometrial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1980;4:481–489.

Nucci MR, Prasad CJ, Crum CP, et al. Mucinous endometrial epithelial proliferations: a morphologic spectrum of changes with diverse clinical significance. Mod Pathol 1999;12:1137–1142.

Ross JC, Eifel PJ, Cox RS . Primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. A clinicopathologic and histochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:715–729.

Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2003.

Kato N, Katayama Y, Kaimori M, et al. Glassy cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: histochemical, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic observations. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:134–140.

Kushima R, Borchard F, Hattori T . A new aspect of gastric metaplasia in Crohn’s disease: bidirectional (foveolar and pyloric) differentiation in so-called ‘pyloric metaplasia’ in the ileum. Pathol Int 1997;47:416–419.

Kushima R, Yamamoto K, Okabe H, et al. MUC-gene expression in ulcerative colitis-related DALMs: a comparative immunohistochemistry study with colonic tumor. Gastroenterology 2001;120 (Suppl):2284.

Kumagai H, Mukaisho K, Hattori T, et al. Cell kinetic study on histogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus using rat reflux model. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:687–692.

Gersell D . Endometrial papillary syncytial change. Another perspective. Am J Clin Pathol 1989;99:656–657.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from Aichi Prefecture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moritani, S., Kushima, R., Ichihara, S. et al. Eosinophilic cell change of the endometrium: a possible relationship to mucinous differentiation. Mod Pathol 18, 1243–1248 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800412

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800412

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Vorläuferläsionen der Endometriumkarzinome

Der Pathologe (2019)