Abstract

Gastrointestinal phenotype in cervical adenocarcinomas was examined by immunohistochemistry and correlated with morphologic features. Antibody panels included anti-MUC2, MUC6, CD10, chromogranin A (CGA) and HIK1083. In addition, expression of p16INK4, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor which is expressed in a variety of high-risk HPV-related conditions, was studied. A total of 94 invasive adenocarcinomas including 20 minimal deviation adenocarcinomas (MDAs) and 72 adenocarcinomas in situ (AIS) were examined. MDAs were most frequently positive for HIK1083 and/or MUC6, two representative gastric markers, with a rate of 95%, followed by intestinal-type adenocarcinomas (IAs) with a rate of 85% whereas only 27% of 56 usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas (UEAs) were positive. MUC2, a goblet cell marker, was positive in 85% and 25% of IAs and MDAs, respectively, while in only 14% of UEAs. CD10 was positive in 15% of IAs, indicating incomplete intestinal differentiation without a brush border in most of the cases. CGA-positive cells were frequently seen in MDAs and IAs with rates of 60% and 62%, respectively. Nuclear and cytoplasmic p16INK4 positivity was identified in 93% of UEAs, whereas 30% of MDAs were positive for p16INK4. Results in AISs were comparable to their invasive counterparts, but morphologically usual-type AISs identified in eight cases of MDA were frequently positive for HIK1083 (75%) and MUC6 (63%), and p16INK4. Of note was the existence of lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) with atypical features including cytologic abnormalities, and/or papillary projection, which were identified in this study in pure form (n=3) or in association with MDAs (n=6), but not in cases of other types of adenocarcinomas. These observations indicate that gastrointestinal phenotype is frequently expressed in MDAs and IAs, and there seems to be a possible link between MDA, and LEGH and morphologically usual-type AIS with gastric immunophenotype in histogenesis. Frequent absence of p16INK4 expression in MDAs suggests a possibility that high-risk HPV does not play a crucial role in development of MDAs, in contrast to the majority of endocervical adenocarcinomas. p16INK4 immunohistochemistry appears to be a promising diagnostic tool, but pathologists should be aware of frequent negative staining in MDAs, which can be a source of erroneous diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA), also known as adenoma malignum,1 is a form of highly differentiated endocervical adenocarcinoma. In 1997, it was shown to have a gastric phenotype by mucin histochemistry and immunohistochemistry using HIK1083, an antibody recognizing pyloric gland mucin of the stomach.2, 3 This antibody has since then been regarded as a promising diagnostic tool for MDAs.4, 5 However, its usefulness has been in dispute and Mikami et al6, 7 have demonstrated HIK1083 reactivity in pyloric gland metaplasia (PGM) of the cervix, which was described as lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) by Nucci et al.8, 9 These facts have provoked controversy concerning a possible link between LEGH/PGM and MDA, and whether gastric phenotype is specific for these two conditions. In the current study, we have examined cervical adenocarcinomas including MDAs, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), and LEGH/PGM as well as a variety of benign glandular lesions to determine the incidence of gastric phenotypes and to shed light on the issue of histogenesis of MDA, employing antibodies to apomucins encoded by the MUC gene family, CD10 and chromogranin A (CGA), and HIK1083 and anti-p16INK4, the last for showing any relationship to high-risk HPV.

In the gastrointestinal tract, MUC2 and MUC6 are expressed by goblet cells10 and the pyloric glands of the stomach,11, 12 respectively. CD10 is expressed in a variety of tissues and tumors, but in the intestinal mucosa it delineates the brush border of the surface epithelium of the small intestinal mucosa.13 Therefore, HIK1083 and MUC6 can be used as gastric markers, and CD10 and MUC2 as intestinal markers. Although MUC5AC is expressed by superficial and foveolar epithelium of the stomach,12 this marker was shown to be positive in normal endocervical epithelium,14 and thus cannot be used as gastric marker at this particular anatomic site. CGA-positive cells, which are ubiquitous in the gastrointestinal mucosa but typically absent in the normal endocervical glands, are expected to be frequently seen in adenocarcinomas with gastrointestinal phenotype. In fact, some reports described CGA-positive cells in intestinal-type adenocarcinomas of the cervix.15, 16

Recent studies have demonstrated that p16INK4 immunohistochemistry is of diagnostic value for high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV)-related conditions including squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL).17 This protein is overexpressed as a consequence of incorporation of E7 derived from high-risk HPV, and it has been shown to be positive in invasive and in situ adenocarcinomas of the cervix, most of which are also considered to be HPV related.18, 19 The frequent location of LEGH/PGM, a putative precursor of MDA, in the portion of internal os away from the transformation zone,6 prompted the authors to assume that a subset of cervical adenocarcinomas with gastric phenotype may have tumorigenesis distinct from high-risk HPV-related ordinary cervical adenocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

Invasive cervical adenocarcinomas, as well as AISs and a variety of benign glandular lesions, were retrieved from the files of Tohoku University Hospital, Kawasaki Medical School Hospital, and Jikei University School of Medicine, and the consultation files of one of the authors (YM). The glass slides of 150 cases were reviewed; there were 56 usual endocervical-type adenocarcinomas (UEAs), 13 intestinal-type mucinous adenocarcinomas (IAs) including six pure and seven mixed forms, 20 MDAs including 13 pure and seven mixed forms, three endometrioid adenocarcinomas (EAs), four adenosquamous carcinomas, one serous adenocarcinoma, one clear cell adenocarcinoma, and two undifferentiated carcinomas. The UEAs, frequently mucin-poor20 but mostly corresponding to mucinous adenocarcinoma of endocervical type in the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification (1994),1 was defined as adenocarcinoma without morphologic evidence of specific differentiation, and those with goblet cells were regarded as IA. Regarding EAs, we employed the strict criteria as Young suggested20 to regard tumors superficially resembling endometrioid carcinoma of the corpus but having a paucity of intracytoplasmic mucin as UEA, and included only non-mucinous tumors composed of tubular glands with occasional ciliated cells as EAs. When the IAs contained minor components of UEA occupying more than 10%, the tumor was assigned “mixed type IA”. Following the WHO classification,1 MDA was defined as a highly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma with well-formed glands resembling benign glands, but showing distinct nuclear anaplasia or evidence of stromal invasion as represented by desmoplastic reaction at least in limited areas. Tumors showing features of MDA but having occasional marked architectural complexity and/or solid components were designated as mixed-type MDA, that is, mucinous adenocarcinoma with features of MDA. MDA with features of IA or EA was not identified. A total of 55 AISs related to invasive adenocarcinoma and 17 pure AISs were also included in the study. AIS was defined as glandular lesions characterized by atypical columnar cells with anaplastic nuclei and occasional mitotic figures, lining pre-existing endocervical glands without crowding, irregular distribution, and architectural complexity, and any evidence of stromal invasion. The classification of AISs followed that for invasive adenocarcinomas, and usual, intestinal, and endometrioid type were identified.

For comparison, normal endocervical glands and a variety of benign glandular conditions identified in 101 cases, such as nabothian cysts (15 foci), tunnel clusters (12 foci), microglandular hyperplasias (six foci), tubal metaplasias (eight foci), endocervical glandular hyperplasias, not otherwise specified (EGH) (20 foci), and LEGH/PGM were also examined. LEGH/PGM, which was defined as proliferation of small glands arranged in a lobular fashion surrounding dilated endocervical glands,6, 8 were identified in one patient with IA, 10 with MDA, and nine who underwent hysterectomy for benign diseases. In the process of the review, nine cases of LEGH/PGMs with atypical features, including nuclear atypia, loss of polarity, mitotic figures, and papillary architecture in a variety of combinations, were identified in pure form or in association with MDA, and were also examined.

All hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were reviewed for confirmation of the diagnoses by two of authors (YM, TK), and representative blocks were selected for immunohistochemical study. The antibodies, vendor sources, working dilutions, and pretreatment for antigen-retrieval are listed in Table 1. Sections (4 μm thick) were cut from paraffin blocks of formalin-fixed tissues, and were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. Immunohistochemical studies were performed using Simle stain® (Nichirei Co., Tokyo, Japan), an indirect conjugated method kit, for mucin staining, and Histofine® (Nichirei Co.), a labeled streptavidin biotin (LSAB) kit, for the others, using standardized protocols. Primary antibodies were incubated with sections after antigen retrieval for all but HIK1083 using autoclave techniques with 10 mM citrate buffer, pH6.0, at 121°C for 5 min. Slides were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen. The immunostaining results were evaluated in a semiquantitative fashion. The distribution of positive cells was scored depending on relative amount of positive cells as follows; score 1 (less than 25%), 2 (25% or more and less than 50%), 3 (50% or more and less than 75%), and 4 (75% or more). The intensity was scored as follows; 0(negative), 1 (weakly positive), 2 (intermediate), and 3 (strongly positive). Regardless of the relative amount of positive cells, staining with an intensity score of 1 or more was regarded as a positive result.

Results

Normal Endocervical Glands and Benign Glandular Conditions

HIK1083, MUC2, and MUC6 were positive in 2% (2/101), 2% (2/101), and 8% (8/101) of normal endocervical glands, respectively. Positive and negative areas for these markers were indistinguishable morphologically. EGHs, nabothian cysts, tunnel clusters, microglandular hyperplasias, tubal metaplasias were negative for HIK1083, MUC2, MUC6, and p16INK4. Only two of 20 EGHs, showed focal and weak luminal staining for CD10, and morphologically normal glands in two cases showed very weak and focal cytoplasmic staining for p16INK4. CGA-positive cells were not identified in any cases.

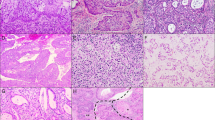

LEGH/PGMs were frequently positive for HIK1083 and MUC6 with rates of 95% (19/20) and 75% (15/20), respectively (Figures 1a and b). MUC2 was less frequently positive with a rate of 15% (3/20). CGA-positive cells were identified in 80% (16/20) of cases. CD10 immunoreactivity was not observed. Regarding p16INK4, only weak cytoplasmic staining was identified in limited areas in 55% (11/20) of cases.

LEGH (a and b), MDA (c–g), and usual endocervical-type adenocarcinoma (h–l). LEGH (a, H&E stain) showing immunoreactivity for HIK1083 (b). MDA (c, H&E stain) decorated with HIK1083 (d), anti-MUC6 (e), and anti-MUC2 (f). Chromogranin A (CGA)-positive cells identified in MDA (g). Usual endocervical-type adenocarcinoma (h, H&E stain) that are positive for HIK1083 (i) and CD10, with linear staining pattern along apical side of cells (j). Some neoplastic cells with anaplastic nuclei (k) are positive for CGA. Immunoreactivity for p16INK4 identified in the majority of cases of usual-type endocervical adenocarcinomas (l).

Invasive Adenocarcnomas

Results of immunostaining are summarized in Table 2. HIK1083 was most frequently positive in cases of MDA (Figures 1c and d) with a rate of 75% (15/20), followed by IAs with a rate of 23% (3/13). In the mixed type IAs, positive staining was predominantly identified in the portion with intestinal morphology. On the other hand, a minority of UEAs was positive for HIK1083 with a rate of 7% (4/56) (Figures 1h and i). MUC6, another marker for pyloric gland phenotype, was also frequently positive in MDAs (Figure 1e) and IAs with rates of 65% (13/20) and 69% (9/13), respectively. Only 23% (13/56) of UEAs were positive for MUC6. HIK1083 and/or MUC6-positive and both negative UEAs were indistinguishable from each other based on morphology alone. In all, 95% (19/20) of MDAs were positive for HIK1083-and/or MUC6, and 45% (9/20) were positive for both HIK1083 and MUC6 (Table 3). In contrast, 27% (15/56) of UEAs were positive for HIK1083 and/or MUC6, and only 4% (2/56) were positive for both. In cases of MDA, 30% (6/20) and 20% (4/20) were positive for HIK1083 only and MUC6 only, respectively, whereas in cases of UEA, 4% (2/56) and 20% (11/56) were positive for HIK1083 only and MUC6 only, respectively. Only 8% (1/13) of IAs were positive for both HIK1083 and MUC6, but 85% (11/13) were positive for HIK1083 and/or MUC6, and 15% (2/13) and 69% (9/13) were positive for HIK1083 only and MUC6 only, respectively. MUC2, a marker for goblet cells, was most frequently positive in IAs with a rate of 85% (11/13), and in occasional MDAs with a rate of 25% (5/20) (Figure 1f). Only 14% (8/56) of UEAs were positive for MUC2.

The mean distribution scores of immunoreactivity in positive cases of MDAs, IAs, and UEAs were 2.0(1-4), 1(1), 1.5(1-2) for HIK1083, 2.4(1-4), 2.4(1-4), 1.9(1-4) for MUC6, and 1(1), 2.3(1-4), 1.1(1-2) for MUC2 (Table 4a). The mean intensity scores in the same order were 2.9(2-3), 3(3), 2.8(2-3) for HIK1083, 1.8(1-3), 2.3(2-3), 1.8(1-3) for MUC6, and 2.7(1-3), 1.9(1-3), 2.4(1-3) for MUC2 (Table 4b). Differences in mean distribution and intensity scores of HIK1083 and MUC6 staining between pure MDAs and UEAs were not statistically significant. No positive staining for HIK1083, MUC2, and MUC6 was identified in EAs, serous adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinomas, and undifferentiated carcinomas, except one adenosquamous carcinoma did stain positive for MUC6.

CD10 was positive in a minority of UEAs (Figure 1j), IAs, and EAs, with rates of 7% (4/56), 15% (2/13), and 33% (1/3), respectively. The staining pattern was mostly linear along the luminal side of neoplastic glands, but occasional cytoplasmic staining was also observed in some tumors including IAs.

CGA-positive cells were frequently identified in IAs and MDAs (Figure 1g) with a rate of 62% (8/13) and 60% (12/20), respectively. In contrast, only 18% (10/56) of UEAs contained CGA-positive cells. Five of 10 UEAs with CGA-positive cells were positive for at least one or more of HIK1083, MUC2, and MUC6. Three of four HIK1083-positive UEAs had CGA-positive cells, whereas three of 13 MUC6-positive and two of eight MUC2-positive UEAs had CGA-positive cells. CGA-positive cells contained mostly small round or ovoid nuclei, and round, triangular, or spindle-shaped cytoplasm, and were located in the basal site of the neoplastic glands in general, although one UEA and one undifferentiated carcinoma contained unequivocal neoplastic cells with large anaplastic nuclei, showing diffuse cytoplasmic staining for CGA (Figure 1k).

The vast majority of UEAs and IAs showed nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for p16INK4 (Figure 1l) with rates of 93%(52/56) and 92%(12/13), respectively, and all EAs, serous adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinomas, and undifferentiated carcinomas were also positive for p16INK4. In contrast, only 30%(6/20) of MDAs were positive for this marker. Distribution scores of p16INK4 immunoreactivity in positive cases ranged from 1 to 4 (mean, 3.0) in MDAs, and 2 to 4 (mean, 3.6) in UEAs; this difference was not statistically significant (Table 4a). All IAs showed score 4 distributions. Intensity score for p16INK4 staining ranged from 1 to 3 (mean, 2.7) in UEAs, 1 to 3 (mean, 1.9) in MDAs, and 2 to 3 in IAs (mean, 2.9) (Table 4b). This difference was also not statistically significant.

Adenocarcinoma In Situ (AIS), MDA-unrelated

AISs, except those in association with MDA, showed staining patterns comparable with their invasive counterparts (Table 2). Five of 42 (12%) usual-type, three of 18 (17%) intestinal type, and none of four endometrioid-type AISs were positive for HIK1083. MUC6 and MUC2 were frequently positive in intestinal AISs with positive rates of 67% (12/18) and 78% (14/18), respectively. CD10 was positive in 10% (4/42) of usual-type AISs, and 6% (1/18) of intestinal AISs.

Lobular Endocervical Glandular Hyperplasia (LEGH)/Pyloric Gland Metaplasia (PGM) with Atypical Features, and AIS in Association with MDA

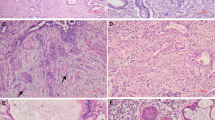

In the current series, a subset of glandular lesions showing architecture of LEGH/PGM with some atypical features were identified (Figures 2 and 3). The atypical features were defined as follows: (1) nuclear enlargement, (2) irregular nuclear contour, (3) distinct nucleoli, (4) coarse chromatin texture, (5) loss of polarity, (6) occasional mitotic figures, (7) apoptotic bodies and/or nuclear debris in the lumen, (8) infolding of epithelium or distinct papillary projection with fine fibrovascular stroma (Figures 2a and 3). In the process of the review, nine examples with at least four of these features were identified, six among 20 MDAs, and three in its pure form without associated invasive adenocarcinomas. Atypical LEGH/PGMs were not identified in cases of UEAs. Of six MDA-associated LEGH/PGMs with atypical features, four were identified in 13 cases of pure MDAs, and two in seven mixed MDAs. In these six cases carcinomatous components were close to or adjacent to foci of LEGH with atypical features. In areas a mixture of both components was seen. Eight of nine atypical LEGH/PGMs were associated with typical LEGH/PGM (Figures 2b), and five were associated with both typical LEGH/PGM and MDA. Cases with MDA in association with AIS of usual-type or atypical LEGH/PGM are summarized in Table 5. Among 14 such MDA cases, six had typical LEGH/PGMs, of which five were associated with atypical LEGH/PGMs and one with usual-type AIS. On the other hand, among eight MDAs without typical LEGH/PGM, seven were associated with usual-type AIS and one with atypical LEGH/PGM. The age of the patients with atypical LEGH and usual-type AIS in association with MDA ranged from 40 to 65 years (mean, 50 years) and from 33 to 60 years (mean, 50.7 years), respectively, and the age of those with typical LEGH only ranged from 42 to 72 years (mean 50.8 years).

Atypical features in LEGH. Small glands forming lobules without nuclear anaplasia in the portion of typical LEGH (a). Atypical LEGH with some nuclear enlargement and irregularity, and conspicuous nucleoli (b). Papillary growth with fine fibrovascular stroma with relatively bland nuclear morphology but some nuclear irregularity and loss of polarity (c). Occasional distinct nuclear atypia in the papillary area located in the cystically dilated space.

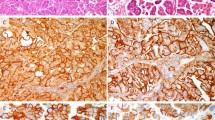

Immunohistochemically, atypical LEGH/PGMs were frequently positive for HIK1083 and MUC6 with rates of 78% (7/9) and 67% (6/9), respectively (Table 2). On the other hand, AISs of usual-type related to MDA were also frequently positive for these two markers (Figure 4) with rates of 75% (6/8) and 63% (5/8) of cases. Expression of p16INK4 was less frequently seen in atypical LEGH/PGMs associated with MDA with a rate of 33% (2/6), but was observed in 75% (6/8) of usual-type AISs related to MDA (Figure 4). Three of eight MDAs with usual-type AIS showed p16INK4 immunoreactivity, whereas only one of six MDAs with atypical LEGH/PGM was positive. CGA-positive cells were identified in 67% (6/9) of atypical LEGH/PGMs and 50% (4/8) of usual-type AISs related to MDA.

Discussion

The current study has demonstrated that MDA shares gastric immunophenotypes with LEGH/PGM, that is, positive staining for HIK1083 and MUC6, and harbors CGA-positive cells, and that IA was frequently positive for MUC2, a goblet cell marker. UEA can be positive for gastrointestinal as well as neuroendocrine markers only occasionally in limited areas. The co-expression of intestinal and gastric phenotypes was not uncommon. Interestingly, CD10 immunoreactivity was positive in a minority of IAs, indicating that intestinal differentiation in IAs is incomplete without well-formed brush borders, and the term goblet cell differentiation rather than intestinal differentiation is much more appropriate in the majority of cases. Finally, MDA may arise in association with morphologically usual but phenotypically gastric AIS, or LEGH/PGM with or without atypical features. In addition, MDAs less frequently express p16INK4, in contrast to UEAs and IAs. These results provoke discussion on two important issues–the concept of MDA and its histogenesis.

The origin of MDA has been uncertain, but a possible relationship to LEGH/PGM was suggested based on immunohistochemical studies.2, 6, 7 The current study has shed further light on this issue. A review of 20 cases of MDA demonstrated coexistence of LEGH/PGM with some atypical features or morphologically usual-type AIS. Six MDAs accompanied typical LEGH/PGMs, of which five had atypical LEGH/PGMs, while seven of eight MDAs without LEGH/PGM were associated with morphologically usual-type AISs. In the current study, only 12% of MDA-unrelated usual-type AISs were positive for HIK1083, while 75% of MDA-related usual-type AISs were positive for HIK1083. Therefore, it seems realistic that MDA can be derived from both LEGH/PGM and morphologically usual-type AIS showing gastric phenotype.

LEGH/PGMs with atypical features are considered to share some morphologic features with AISs. Although nuclear morphology was apparently bland, nuclear enlargement, irregular nuclear contour, conspicuous nucleoli, pseudostratification, occasional mitosis, or apoptotic bodies were observed in various combinations. A striking feature was papillary growth with fine fibrovascular stroma, projecting into the cystically dilated spaces, which is not a feature of benign endocervical glandular lesions. The degree of nuclear abnormality varied in areas, but distinct nuclear anaplasia was identified in some areas, as shown in Figures 3b and d. These atypical features appear to indicate the neoplastic nature of this condition, and a possible link between MDA and LEGH/PGM. However, it seems still early to accept the term AIS of LEGH/PGM-type, AIS of gastric-type, or MDA in situ because of uncertainty about the biological nature of this lesion and the possibility of overtreatment by using the term AIS. To establish a consensus terminology, prospective studies demonstrating a risk for developing MDAs among patients with LEGH/PGM with atypical features, and molecular studies revealing genetic abnormalities, are awaited. Limited data, however, suggest that an incidentally found prototypical LEGH/PGM without any atypical features does not seem to justify radical treatment, although it may be a risk factor. Mikami et al7 demonstrated the incidence of LEGH/PGM to be 0.7% in consecutive hysterectomy specimens in a single institution (8/1169). In these cases, three were in association with florid endocervical glandular hyperplasia, but atypical features as identified in the current study were not observed. In addition, the current series included cases retrieved from the consultation files with a resultant selection bias. Therefore, the incidence of LEGH/PGMs with atypical features in the general population seems very low, and the occurrence of adenocarcinoma in association with LEGH/PGM is considered to be a rare event. At this point, we believe atypical LEGH/PGM would be an appropriate term for describing this particular lesion.

Another striking feature in this study was the less frequent expression of p16INK4 in cases of MDA. Recent studies have demonstrated that diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for p16INK4 was significantly associated with high-risk HPV-related lesions.17, 18 Our study demonstrated frequent expression of this protein in 93% of UEAs, whereas MDAs less frequently expressed with a rate of 30%. Even when positive, positive cells were decreased and the staining intensity was weaker. IAs were close to UEAs with regard to incidence of p16INK4 expression. In general, AIS and SIL, now recognized as HPV-related precursors of invasive carcinoma, occur in the transformation zone of the cervix. In contrast, LEGH/PGM frequently involves the portion of internal os away from the transformation zone.6 Therefore, it seems reasonable for MDAs derived from LEGH not to express p16INK4, possibly due to a lack of high-risk HPV being involved in the tumorigenesis. On the other hand, morphologically usual-type AISs related to MDA more frequently expressed p16INK4 with a rate of 75%, indicating that MDA could arise in association with either high-risk HPV-related morphologically usual-type AIS or non-high-risk HPV-related LEGH/PGM. Further study is clearly required to demonstrate HPV DNA status in these particular lesions. Another important implication is that p16INK4 immunostaining does not have a discriminative value in distinguishing MDA from benign endocervical glandular lesions. Pathologists should be aware of this diagnostic pitfall. It is also the case in distinguishing cervical adenocarcinoma from endometrial carcinoma. Positive staining for CEA and absence of vimentin and estrogen receptor have been considered suggestive of endocervical rather than endometrial origin,21, 22 and recently McCluggage and Jenkins23 demonstrated diffuse and strong p16INK4 expression is indicative of a cervical origin. It should be noted, however, that absence of p16INK4 staining does not rule out this possibility.

The final issues to be discussed are the concept of MDA, and whether “mucinous adenocarcinoma of gastric-type” is a distinct entity and acceptable term as a substitute for MDA. Originally MDA was described as an highly differentiated form of endocervical mucinous adenocarcinoma, and thus can be a diagnostic challenge for pathologists. Because of the overemphasis of its benign appearance, a variety of benign endocervical glandular lesions have been confused with MDA,20 and the criteria have been refined to define MDA as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma showing bland morphology, but with recognizable anaplasia at least in some areas.24 From a practical point of view, the significance of the term MDA appears to emphasize the existence of such a benign-looking tumor which may result in underdiagnosis. In this regard, the term MDA is preferred rather than the commonly used term “adenoma malignum”. On the other hand, a distinction between MDA and well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma is occasionally arbitrary, and in reality a gray zone exists resulting in interobserver variability in making the diagnosis, although the distinction might not be so crucial in patient management. There may be argument that “gastric-type adenocarcinoma” does exist as a distinct entity which corresponds to MDA or nonintestinal type mucinous adenocarcinoma which Young insisted on separating from common mucin-poor endocervical adenocarcinomas.20 However, there is a continuum in morphology and gastrointestinal immunophenotype which can be shared by typical MDA, mixed form of MDA, and UEAs. Interestingly, Kuragaki et al25 has demonstrated somatic mutations of STK11, a tumor suppressor gene responsible for the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, in six of the 11 mucinous MDAs, and speculated that this mutation may play an important role in the development of MDA, but they identified the same mutation in one of 19 mucinous adenocarcinomas other than MDAs, indicating that this genetic abnormality is characteristic but not specific for MDA. The STK11 mutation might well characterize the “gastric-type adenocarcinoma” or MDA. In the author's opinion, however, since classification of tumors should be based on light microscopic appearance as evaluated by routine H&E staining, the term “gastric-type adenocarcinoma” does not seem to be justified unless further studies demonstrate a clinical significance of this particular phenotypic expression in the tumor. Finally, the fact that tumors morphologically classified as mucinous adenocarcinoma of endocervical-type in the current WHO classification1 show the gastrointestinal immunophenotype indicates that this is a phenotypically heterogeneous group of neoplasms and that the term adenocarcinoma of nonspecific type or UEAs as we used in the study, rather than mucinous adenocarcinoma of endocervical-type, may be appropriate.

In summary, we have assessed the gastrointestinal phenotype in endocervical adenocarcinomas. UEAs are heterogenous neoplasms including those with gastric and/or intestinal phenotype, some of which show a morphologic spectrum shared by MDA. Some MDA may arise from usual-type AIS but others from LEGH/PGM. Absent or decreased p16INK4 immunoreactivity in LE:GH/PGM suggests that the former process might be high-risk HPV related, whereas the later unrelated, although further studies are awaited before a final conclusion can be drawn.

References

Scully RE, Bonfiglio TA . Histological Typing of Female Genital Tract Tumours. Springer: Berlin, 1994.

Ishii K, Hosaka N, Toki T, et al. A new view of the so-called adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix. Virchows Arch 1998;432:315–322.

Ishihara K, Kurihara M, Goso Y, et al. Peripheral alpha-linked N-acetylglucosamine on the carbohydrate moiety of mucin derived from mammalian gastric gland mucous cells: epitope recognized by a newly characterized monoclonal antibody. Biochem J 1996;318:409–416.

Ishii K, Katsuyama T, Ota H, et al. Cytologic and cytochemical features of adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix. Cancer 1999;87:245–253.

Utsugi K, Hirai Y, Takeshima N, et al. Utility of the monoclonal antibody HIK1083 in the diagnosis of adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol 1999;75:345–348.

Mikami Y, Hata S, Fujiwara K, et al. Florid endocervical glandular hyperplasia with intestinal and pyloric gland metaplasia: worrisome benign mimic of "adenoma malignum". Gynecol Oncol 1999;74:504–511.

Mikami Y, Hata S, Melamed J, et al. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia is a metaplastic process with a pyloric gland phenotype. Histopathology 2001;39:364–372.

Nucci MR, Clement PB, Young RH . Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia, not otherwise specified: a clinicopathologic analysis of thirteen cases of a distinctive pseudoneoplastic lesion and comparison with fourteen cases of adenoma malignum. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:886–891.

Mikami Y, Manabe T . Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia represents pyloric gland metaplasia? Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:323–324 author reply 325–326.

Winterford CM, Walsh MD, Leggett BA, et al. Ultrastructural localization of epithelial mucin core proteins in colorectal tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 1999;47:1063–1074.

De Bolos C, Garrido M, Real FX . MUC6 apomucin shows a distinct normal tissue distribution that correlates with Lewis antigen expression in the human stomach. Gastroenterology 1995;109:723–734.

Machado JC, Nogueira AM, Carneiro F, et al. Gastric carcinoma exhibits distinct types of cell differentiation: an immunohistochemical study of trefoil peptides (TFF1 and TFF2) and mucins (MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6). J Pathol 2000;190:437–443.

Trejdosiewicz LK, Malizia G, Oakes J, et al. Expression of the common acute lymphoblastic leukaemia antigen (CALLA gp100) in the brush border of normal jejunum and jejunum of patients with coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol 1985;38:1002–1006.

Riethdorf L, O'Connell JT, Riethdorf S, et al. Differential expression of MUC2 and MUC5AC in benign and malignant glandular lesions of the cervix uteri. Virchows Arch 2000;437:365–371.

Savargaonkar PR, Hale RJ, Mutton A, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in cervical carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:139–141.

Chavez-Blanco A, Taja-Chayeb L, Cetina L, et al. Neuroendocrine marker expression in cervical carcinomas of non-small cell type. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:368–374.

Keating JT, Cviko A, Riethdorf S, et al. Ki-67, cyclin E, and p16INK4 are complimentary surrogate biomarkers for human papilloma virus-related cervical neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:884–891.

Riethdorf L, Riethdorf S, Lee KR, et al. Human papillomaviruses, expression of p16, and early endocervical glandular neoplasia. Hum Pathol 2002;33:899–904.

Negri G, Egarter-Vigl E, Kasal A, et al. p16INK4a is a useful marker for the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the cervix uteri and its precursors: an immunohistochemical study with immunocytochemical correlations. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:187–193.

Young RH, Clement PB . Endocervical adenocarcinoma and its variants: their morphology and differential diagnosis. Histopathology 2002;41:185–207.

McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, McBride HA, et al. A panel of immunohistochemical stains, including carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, and estrogen receptor, aids the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:11–15.

Kamoi S, AlJuboury MI, Akin MR, et al. Immunohistochemical staining in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas: another viewpoint. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:217–223.

McCluggage WG, Jenkins D . p16 immunoreactivity may assist in the distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:231–235.

Gilks CB, Young RH, Aguirre P, et al. Adenoma malignum (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) of the uterine cervix. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:717–729.

Kuragaki C, Enomoto T, Ueno Y, et al. Mutations in the STK11 gene characterize minimal deviation adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Lab Invest 2003;83:35–45.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Joji Haratake and Takahiko Kasai (Kurobe, Japan), Kishichiro Watanabe (Kanazawa, Japan), Hiroshi Kurumaya (Kanazawa, Japan), Akitaka Nonomura (Kashihara, Japan), Yoshio Oda (Kanazawa, Japan), Tetsuo Hamada (Kitakyushu, Japan), and Takayuki Nojima (Uchinada, Japan) for contributing archival materials of endocervical adenocarcinomas. We also thank Mrs Fumiko Date in the Department of Histopathology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medical Science, Sendai, Japan, for her skillful technical support, and Professor Tsunehisa Kaku (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) for his suggestion and advice regarding LEGH with atypical features.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikami, Y., Kiyokawa, T., Hata, S. et al. Gastrointestinal immunophenotype in adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix and related glandular lesions: a possible link between lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia/pyloric gland metaplasia and ‘adenoma malignum’. Mod Pathol 17, 962–972 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800148

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800148

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of immunophenotypic characterization of endocervical adenocarcinoma using CLDN18, CDH17, and PAX8 in association with HPV status

Virchows Archiv (2022)

-

A retrospective study on incidence, diagnosis, and clinical outcome of gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma in a single institution

Diagnostic Pathology (2021)

-

Clinicopathological features and outcomes in gastric-type of HPV-independent endocervical adenocarcinomas

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

Genetic characteristics of gastric-type mucinous carcinoma of the uterine cervix

Modern Pathology (2021)

-

Massively parallel sequencing analysis of 68 gastric-type cervical adenocarcinomas reveals mutations in cell cycle-related genes and potentially targetable mutations

Modern Pathology (2021)