Abstract

Study design:

Prospective, cross-sectional study, based on cases of spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

Three outpatient medical departments in Seoul, Korea.

Objectives:

To assess depressive symptoms in patients on clean intermittent catheterization after SCI.

Methods:

In total, 102 subjects (68 males and 34 females, mean age 39.5 with a range of 18–75 years) were included in the primary analysis. A control group of 110 was selected from the routine health checkup. All subjects completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Results:

For patients and controls, the average total BDI scores were 20.3±1.0 and 11.4±0.5, respectively (P<0.001). With regard to severity of depression among patient groups, three (3.0%) reported normal; four (3.9%) reported mild to moderate depression; 24 (23.5%) reported moderate to severe depression; and 71 (69.6%) reported severe depression. On the multivariate logistic regression analysis, a positive association with the risk of depression was observed in gender and type of catheterization. Female patients had a 3.8-fold higher risk (odds ratio (OR) 13.83; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.42–10.31; P=0.008) of depression than male patients. In the same model, patients who were unable to perform catheterization independently had a 4.6-fold higher risk (OR 4.62; 95% CI 1.67–12.81, P=0.003) of depression than those who were able to perform self-catheterization.

Conclusions:

The results demonstrate that the patients with neurogenic bladder secondary to SCI have higher degrees of depression than normal population. In addition, our findings also suggest that depression is closely related to gender and patient's ability to perform self-catheterization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with neurogenic bladder (NB) are at risk for many complications, including urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence and deterioration of the upper urinary tracts with potential loss of renal function. Before the development of modern methods of bladder management, renal failure secondary to NB was the most common cause of death in these patients. Thus, management of the lower urinary tract is crucially important in patients with NB to prevent damage to the upper tract and, thus, preserve renal function. The goal of management is to allow the bladder to store a reasonable volume of urine at low pressure and empty it at appropriate intervals. Over the past 30 years, clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) has been used for the management of these patients. With intermittent catheterization individuals are able to empty the bladder on a regular basis with a low urinary tract infection rate and good continence between catheterizations.

However, before deciding the management plan on the bladder dysfunction in patients with SCI, factors, such as the type of voiding dysfunction, level of injury, and patient's ability to perform self-catheterization, dressing and transfers, should be considered. Bladder drainage is achieved through indwelling catheters, intermittent catheterizations, suprapubic catheters, condom sheath catheters, or a combination of these methods. The choice of catheter or type of bladder drainage should be made on an individual basis, taking into account many factors such as patient preference, sex of the patient, level of injury, functional status, financial concerns, and the patient's desire for sexual intercourse.1 The long-term outcome of NB, with better treatment has improved considerably. Currently with a better understanding of the principles of bladder management the complication rate is far lower and the life expectancy is equal to those of people of the same age and sex. The majority of patients are able to lead a normal social, family and professional life. The quality of life of individuals with NB has been far higher. However, although CIC may increase the life span of selected patients with NB, patients remain ill with progressive chronic neurologic disease. Additionally, most patients need continuous medication and long-term medical follow-up. Therefore, patients on CIC may have an impaired quality of life, with physical, social and emotional dysfunction, which is not necessarily examined using the traditional clinical approach.

Management of NB requires a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach. Patients with NB often suffer from psychological problems. Perhaps the greatest potential adverse emotional consequence of NB is depression.2 Kennedy and Rogers3 examined the prevalence of anxiety and depression longitudinally in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). Their results illustrated the highest scores in the acute phase of injury and it highlighted the need for interventions to prevent and treat psychological disorders during this period. However, even after the patient is stable, attention should be paid to the psychological aspect of management because SCI often results in long-term physical and emotional disabilities.

When the patient is stable, individual is able to perform activities of daily life. Thus, performing quality of life assessment after acute state will provide the most useful information regarding permanent physical and emotional disabilities. Unfortunately, we know little about the association between depressive symptoms in neurogenic patients after acute state, particularly among ethnic minorities. To our knowledge, no such study had ever been performed with an Asian population. The aim of our study was to assess depressive symptoms in a population of patients with NB owing to SCI.

Materials and methods

Patients

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards and all patients signed an informed consent agreement. We conducted a prospective trial involving patients on CIC due to NB at three outpatient departments at the hospitals (Departments of Urology and Rehabilitation Medicine at the Seoul National University Hospital, and Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at the National Rehabilitation Center) in Seoul, Korea. The great majority of our patients were those in our outpatients’ clinic but the rest of patients were hospitalized for the routine evaluation or health check-up at the time of assessment. Outpatients had the questionnaires administered at their follow-up visit and hospitalized patients within the first 2 days of their hospitalization. Patients were consecutively preselected by the doctors (HS, NJP and SJO) of the three outpatients departments, who were informed about the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients who were eligible and willing to participate in the study were then assessed by an independent examiner. Study inclusion criteria were: age 18 years or older, good visual acuity, the ability to communicate, and understand and comply with the study requirements. Exclusion criteria were patients in a confused state, those who cannot read the questionnaire, or those who fail to give consent. In cases with an incomplete workup or incomplete information, the results of the survey were also excluded from the final analysis.

The 110 patients (70 males and 40 females) with NB who agreed and signed the informed consent form to participate in the study were evaluated. Out of 110 patients who enrolled in the study, 102 (68 males and 34 females, mean age 39.5 with a range of 18–75 years) were included in the primary analyses. All patients were in the chronic phase and mean duration of CIC was 16.4 months. In all, 73 (71.6%) were able to perform self-catheterization and 29 (28.4%) were unable to perform self-catheterization. A control group of 110 was randomly selected from the population pool among the subject who visited Health Promotion Center of Seoul National University Hospital for routine health checkup. All controls lived in the same geographical region as the patients and frequency matching ensured an equal age distribution among patients and controls.

Methods

Since most respondents were not sufficiently able to complete questionnaire, interviewer assisted or administered forms were used. Information on the demographic characteristics was collected by questionnaires.

We assessed the depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).4 The BDI is a self-report screening test for depression and is scored as an index of severity of depressed mood. A validated Korean version of SF-36 was used in this study,5 and the BDI has been a widely used survey for Korean population.6, 7, 8 Mean BDI score of a healthy Korean population was reported to be 12.7, which is significantly higher than that of the Western population.5 A BDI score of 21 also has been suggested as a cutoff value for the diagnosis of depression for the Korean population.5 Individual items assessed on the BDI include sadness, pessimism, sense of failure, dissatisfaction, guilt, punishment, dislike of self, self-accusation, suicidal ideation, crying, agitation, social withdrawal, indecisiveness, body image, loss of appetite, fatigability, insomnia, retardation, loss of weight, somatic preoccupation, and low level of energy. Each of the 21 items is scored from 0 to 3.

Statistical analysis

The survey responses were coded and analyzed with descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard errors or numbers (%). We calculated frequency distributions for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons of continuous data between two groups were made by the Student t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 tests or the Armitage test.

To assess the possible effect of variables on depression, univariate logistic regression analysis was performed. In this univariate analysis, variables with a P-value of <0.25 were entered into the multivariate model as dependent variables. Odds ratios (ORs) for depression (>BDI score 20; which was chosen as the cutoff based on the study for the Korean population)5 with respect to sex, age, education level, income, level of injury, duration of injury, plegics, type of catheterization, and duration of catheterization, and the P-values for trend were estimated by multivariate logistic regression analysis in 102 patients. The associations between these parameters and depression were described using maximum likelihood estimates of relative risk and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on the logistic regression model. CIs were based on the standard errors of the coefficients and a normal approximation. A 5% level of significance was used for all statistical testing and all statistical tests were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using a commercially available analysis program.

Results

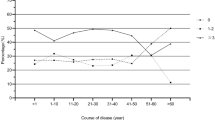

For patients and controls, the average total BDI scores were 20.3±1.0 and 11.4±0.5, respectively (P<0.001). When both patients and controls were divided into two groups according to age, patients younger than 50 years had significantly higher scores than controls younger than 50 years (P<0.001). Significant differences of scores were also seen between patients and controls 50 years old or older (P<0.001). When both patients and controls were divided into two groups according to sex, male patients had significantly higher scores than male control (P<0.001). Significant differences of BDI scores were also seen between female patients and female controls (P<0.001) (Figure 1).

BDI scores of patients according to clinical characteristics and demographics are shown in the Table 1. The demographic variables were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Female patients had higher BDI scores than male patients (24.2±2.0 versus 18.3±1.0, P=0.004). BDI scores of patients 50 years old or older was higher than those of younger than 50 years (25.4±2.9 versus 18.7±0.9, P=0.036). Patients who were unable to perform self-catheterization had higher BDI scores than those who were able to perform self-catheterization (24.3±1.8 versus 18.7±1.1, P=0.010).

To evaluate the influence of clinical parameters on depression, patient characteristics and demographics were included in the univariate logistic model. The univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that sex, age and type of catheterization were possible risk factors of depression. These variables were selected for the multivariate logistic model to determine their association with depression. The other parameters were not appreciably related to depression. On the multivariate model used, a positive association was observed in gender and type of catheterization. Female patients had 3.8-fold higher risk (OR 13.83; 95% CI 1.42–10.31; P=0.008) of depression than male patients. In the same model, patient's ability to perform self-catheterization had more significant impact on the risk of depression than gender. Patients who were unable to perform catheterization independently had 4.6-fold higher risk (OR 4.62; 95% CI 1.67–12.81, P=0.003) of depression than those who were able to perform self-catheterization. However, age lost statistical significance. The results are shown in the Table 2.

Discussion

Although estimated prevalence of depression after SCI is quite variable from study to study, depending on the type of measure, the definition of depression, and whether the taken during rehabilitation, shortly after, or somewhat later, depressive disorders are the most common form of psychologic distress in SCI and appear to be more common than in the nondisabled population.9, 10, 11 The present study also demonstrated that the prevalence of depression in patients with NB was significantly higher than that of the control group.

There is mixed evidence for a relation between depressive symptoms and demographics or injury characteristics. In the present study, except age and sex, no demographic variables such as educational level and income or injury characteristics such as completeness, level or duration of lesion were not associated with depressive symptoms. Craig et al12 noted similar findings in an earlier study. With regard to aging, several studies of multiple components (chronologic age, age at injury onset and time since injury) have found limited relationship between these aging component and general psychosocial outcomes. These studies have generally found chronologic age and age at injury onset to be negatively correlated with psychological outcomes. For instance, Krause and Sternberg13 found that chronologic age was negatively correlated with general life satisfaction and life adjustment, whereas the number of years since SCI onset was positively correlated with the same outcomes. Other researchers found that the poorest psychological outcomes were associated with greater age.14, 15 However, in our study, chronological age was not an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms in SCI population. On the contrary, we found that female patients had 3.8-fold higher risk of depression than male patients. Previous studies have also demonstrated that women are at a substantially higher risk for depressive symptoms.1, 16

Studies have demonstrated not only that depression is not an inevitable reaction to injury, but also that it is not a necessary facet of rehabilitation.3 Previous studies have indicated that depressive symptoms is associated with fewer functional improvement in SCI rehabilitation.17 In comparison, those with the highest expectancies for recovery of functional abilities report less depressive symptoms.18 Tate et al19 found that persons with higher self-report depression scores had greater use of paid personal care attendants than those with lower levels of depression. An interesting finding was an influence of patient's ability to perform self-catheterization on depressive symptoms, with poorer outcomes observed among patients who were unable to perform catheterization independently. This finding represents that functional status of patients may influence patients’ depressive symptoms. Even mild and moderate levels of depression have been found to have a major impact on health, activities of daily living, and interpersonal relationship among nondisabled person.20 It would seem reasonable that they would have an equal or greater effect on patients with NB. Additionally, because the BDI score in patients on carer-assisted catheterization are substantially higher than in those on self-catheterization, they must be of concern to rehabilitation professionals.

Limitations affecting our current findings must be considered. Firstly, one particular weakness was imposed by patient selection. As patients who were willing and able to participate in the study were assessed, there might be a selection bias. Secondly, our study included only Korean population (for normal controls as well as patients). Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to patients of other races or cultures. This study needs to be replicated in other non-Korean to improve its generalizability. Thirdly, there are a number of methodologic problems associated with the measurement of depression. Our study is limited by the lack of a structured psychiatric interview. In addition, the BDI was the sole measure of depressive symptoms. Although the BDI has been used successfully with SCI populations, it is suggested that the use of standardized rating scales such as the BDI in SCI populations is inappropriate, because these instruments contain somatic items.21 The BDI can be used for screening purposes,22 but the use of measures of general psychologic distress may lack specificity for diagnostic purposes in SCI populations. The BDI does not measure depression according to standardized criteria for diagnostic disorders; rather, this instrument provides an index of the relative intensity of certain behaviors that often accompany a depressive episode. Scores on the BDI may reflect a cluster of behaviors that might be associated with diagnosable depression or another condition, such as anxiety disorder.23 Probably, most appropriate would be a psychological tool specifically developed to measure depression in SCI populations. Fourthly, investigations on adjustment should take into account the influence of personality-related factors such as the coping ability, the general philosophical outlook, and religious and other values. Fifthly, occasionally there may be a pre-existing psychiatric disorder. A constellation of psychological or behavioral signs and symptoms can also occur in these patients due to underlying medical disease, metabolic disturbances and medications.24 Finally, in the present study, types of supportive measures and the suitability of support recipients were not considered.

The problems associated with this study and implications highlighted by its findings indicate a number of issues that should be addressed by future research. Principally, although studies have ascertained that depression is more prevalent in NB populations than the general population, few studies provided an empirical analysis of why this difference is identified. Further studies are required to identify the causes of such symptoms by identifying vulnerability and risk factors. More detailed assessment is required for socioeconomic, demographic, personality and comorbidity variables. Future researches should control for the possible confounding contribution of somatic symptoms of physical illness and/or treatment effects to the physical symptoms of depression and should articulate clear diagnostic parameters by established and accepted criteria using standard interview system.9

Conclusion

Comprehensive care of patients on CIC due to NB is one of the greatest clinical challenges in healthcare. The results demonstrate that the patients with NB secondary to SCI have higher degrees of depression than normal population. In addition, our findings also suggest that depression is closely related to gender and patient's ability to perform self-catheterization.

References

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J . Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2000; 81: 1099–1109.

Kennedy P, Rogers BA . Anxiety and depression after spinal cord injury: a longitudinal analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2000; 81: 932–937.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J . An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr 1961; 4: 561–571.

Hahn HM, Yun TH, Shin YW, Kim KH, Yoon DJ, Chung KJ . A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory in Korea. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1986; 25: 487–502.

Kim O . The relationship of depression to health risk behaviors and health perceptions in Korean college students. Adolescence 2002; 37: 575–583.

Kim O . Sex difference in social support, loneliness, and depression among Korean college students. Psychol Rep 2001; 88: 521–526.

Ku JH, Jeon YS, Kim ME, Lee NK, Park YH . Psychological problems in young men with chronic prostatitis-like symptoms. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2002; 36: 296–301.

Benevento BT, Sipski ML . Neurogenic bladder, neurogenic bowel, and sexual dysfunction in people with spinal cord injury. Phy Ther 2002; 82: 601–612.

Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, Rapaport MH . Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 1411–1417.

Jacob K, Zachariah K, Bhattahcharji S . Depression in spinal cord injury: methodological issues. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 377–380.

Frank RG, Elliott TR, Corcoran JR, Wonderlich SA . Depression after spinal cord injury: is it necessary? Clin Psychol Rev 1987; 7: 611–630.

Kendall PC, Hollon SD, Beck AT, Hammer CL, Ingram RE . Issues and recommendations regarding use of the Beck Depression Inventory. Cog ther Res 1987; 11: 289–299.

Blumenfield M, Schoeps MM . Psychological Care of the Burn and Trauma Patients. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore 1993, pp 1–147.

Elliott TR, Frank RG . Depression following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1996; 77: 816–823.

Craig AR, Hancock KM, Dickson HG . Spinal cord injury: a search for determinants of depression two years after the event. Br J Clin Psychol 1994; 33: 221–230.

Frank RG et al. Dysphoria: a major symptom factor in persons with disability or chronic illness. Psychiatry Res 1992; 43: 231–241.

Fuhrer MJ, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Clearman R, Young ME . Depressive symptomatology in persons with spinal cord injury who reside in the community. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1993; 74: 255–260.

Malec J, Neimeyer R . Psychologic prediction of duration of inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation and performance of self-care. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1983; 64: 359–363.

Umlauf RL, Frank RG . Cluster analysis, depression, and ADL status. Rehab Psychol 1987; 32: 39–44.

Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Maynard F, Dijkers M . Predicting depression and psychological distress in persons with spinal cord injury based on indicators if handicap. Am J Phys Med Rehab 1994; 73: 175–183.

Krause JS, Sternberg M . Aging and adjustment after spinal cord injury: the roles of chronological age, time since injury, and environmental change. Rehab Psychol 1997; 42: 287–303.

Kerr WG, Thompson MA . Acceptance of disability of sudden onset in paraplegia. Paraplegia 1972; 10: 94–102.

Cook DW . Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: incidence of denial, depression and anxiety. Rehab Psychol 1979; 26: 97–104.

Furlan JC, Krassioukov AV, Fehlings MG . The effects of gender on clinical and neurological outcomes after acute cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2005; 22: 368–381.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, SJ., Shin, HI., Paik, NJ. et al. Depressive symptoms of patients using clean intermittent catheterization for neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 44, 757–762 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101903

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101903

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Psychosocial Factors in Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Implications for Multidisciplinary Care

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2022)

-

Anxiety Levels and Sexual Functions of Patients Performing Clean Intermittent Catheterization

Sexuality and Disability (2021)

-

The use of mirabegron in neurogenic bladder: a systematic review

World Journal of Urology (2020)

-

Quality of Life and the Neurogenic Bladder: Does Bladder Management Technique Matter?

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2017)

-

Frequency and age effects of secondary health conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a scoping review

Spinal Cord (2013)