Abstract

Study design: Longitudinal observational.

Objectives: (a) To establish a reliable and feasible method to indicate the presence and severity of dysphagia and (b) to establish a course of treatment in individuals presenting with cervical spinal cord injury (CSCI).

Setting: Spinal Cord Injury Center, Werner Wicker Klinik, Bad Wildungen, Germany.

Patients and methods: This is a cross-sectional study of 51 patients consecutively admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of the SCI in-patient service. They were subjected to neurological and fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES). Data concerning artificial respiration, presence of tracheostomy, oral or non-oral feeding were obtained from the medical charts. Statistics were carried out by a calculation of a nonparametric correlation (Spearman).

Results: Five levels of dysphagia could be distinguished. At levels 1 and 2, patients presented with a severe impairment of swallowing, in level 3 aspiration was met by a powerful coughing reflex, level 4 comprised a laryngeal edema and/or a mild aspiration of fluids only and at level 5 laryngeal function was not compromised. On admission, 20 patients with CSCI presented with mild (level 4), eight with moderate (level 3) and 13 with severe dysphagia (levels 1 and 2). In 10 no signs of dysphagia could be detected. After treatment, level 1 was no longer detected, one patient showed level 2, two patients showed level 3, all other patients showed only mild or no signs of dysphagia any longer.

Conclusions: Dysphagia of various severities was present in the majority of these patients with CSCI together with respiratory insufficiency. FEES allows for the detection and classification of dysphagia as well as for an evaluation of the therapeutic management. Under interdisciplinary treatment the prognosis of dysphagia is good.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with cervical spinal cord injury (CSCI) suffer from complete or partial tetraplegia and impairment of sensory and autonomic functions. They also present with a respiratory insufficiency due to the paralysis of breathing muscles, sometimes leading to a temporary or permanent dependence on artificial respiration. If dysphagia is present, pneumonia due to aspiration may develop. Dysphagia will also compromise the quality of life concerning oral diet and ability to communicate. Methods to detect dysphagia have to be reliable as well as feasible under Intensive Care Unit (ICU) conditions. In the management of patients with CSCI and respiratory insufficiency we need guidelines concerning the duration of artificial respiration, the indications for tracheotomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and the recommendations for oral or nonoral feeding. The present study examines the prevalence and severity of dysphagia in patients admitted to our ICU presenting with respiratory insufficiency following acute CSCI in order to make recommendations concerning their management.

Physiology of mastication and swallowing

Swallowing is one of the most frequent courses of movement of the human organism. The swallowing reflex is initiated voluntarily and carried out in three phases: the oral, the pharyngeal and the esophageal phase. The larynx is positioned at the crossing of the paths of respiration and deglutition, but also serves in the function of phonation. As the larynx closes and respiration is inhibited during swallowing, thus aspiration into the lower respiratory tract is prevented. In case of aspiration, the respiratory tract will be cleared by an intact coughing reflex. In case this protecting reflex is lacking, a silent aspiration occurs.

The coordinated action of the swallowing musculature is controlled by the motor and premotor cortex of both hemispheres.1 The striated muscles of mastication, tongue and face are innervated by the trigeminal, facial and hypoglossal nerves. The neurons of the larynx are mainly present in the vagal nerve. The esophageal phase is coordinated between medullary swallowing centers and local intramural nerve plexus, the pharyngeal constrictor muscle being innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve.2,3,4

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is used as a term to describe swallowing disorders compromising the regular transport of food from mouth to stomach. This may be based on structural disorders or on disturbances of the neurological control of swallowing. The leading symptom of neurological dysphagia is aspiration.5 Children with multiple handicap were found to be prone to aspiration.6 But dysphagia is also found in neurological disorders, such as cerebral ischemia or hemorrhage, myasthenia gravis, brain injury, tumors or infections of the brain.7 Patients presenting with cranial nerve palsies in cervical spinal cord injuries were prone to develop the picture of bulbar palsy with acute respiratory distress and dysphagia. The causes for cranial nerve lesions were seen in a direct injury of the nerves, brain-stem edema, injury or ischemia.8

Diagnosis of dysphagia

In order to assess the presence and severity of aspiration as leading symptom of dysphagia, several methods have been established. Videofluoroscopic study of swallowing (VFSS) allows for an observation of deglutition from oral cavity to cardia. The method provides a score for the severity of the aspiration.9 In clinical studies, VFSS has been used to investigate dysphagia following surgical intervention in the oral cavity and hypopharynx10 as well as in patients suffering from severe head injury.11 A systematic review focusing on studies of adults with acute stroke showed that dysphagia is common and clearly linked to chest infections. Interpretation of aspiration on VFSS was assessed as not as straightforward and conferring additional risks.12 Severe complications leading to acute respiratory distress were reported after a ‘barium swallow’ investigation of dysphagia.13 A literature review on swallowing disorder in acute stroke patients did not allow determination of the relative efficacy of VFSS or FEES due to the small size of available studies. But it was indicated that implementation of dysphagia programs were accompanied by substantial reduction in pneumonia rates.14 Studies on patients with acute traumatic brain injury, stroke or extensive head and neck surgery show that FEES is an objective and sensitive tool to diagnose pharyngeal dysphagia as well as determine aspiration status and make recommendations for oral or nonoral feeding. FEES is suited to patients who may be unable to tolerate VFSS.15,16,17

In summary, FEES is easily applicable in the setting of an ICU and may be repeated as often as necessary with little inconvenience to the patient. On the contrary, VFSS is not readily available at the bedside of the patient. The setting cannot be adjusted to patients with tracheotomy and artificial respiration, which are prone to a wheelchair.

Dysphagia in CSCI

Dysphagia related to structural disturbances of larynx and hypopharynx and to disorders of the brain has been investigated to an increasing extent. In contrast, data on dysphagia in patients suffering from CSCI are rare. Some authors point out that anterior spinal surgery is connected with a risk of developing postoperative dysphagia. Two studies estimate voice and swallowing impairment at 45–60% of a population having undergone anterior cervical fusion or discectomy.18,19 After multilevel anterior cervical corpectomy two out of 36 patients,20 after anterior stabilization with combined plate and bone fusion two out of 13 patients suffered from dysphagia.21 In the above-mentioned studies, the majority of patients underwent surgery for spondylotic cervical myelopathy. One study identified vocal fold paralysis in 5% of patients after cervical discectomy as a reason for dysphagia including aspiration.22

In a study using VFSS in patients suffering from CSCI to confirm dysphagia, three predictors were suggested: age, tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation and anterior approach spinal surgery. Dysphagia was found to be present in a significant percentage of those patients.23

Methods

Subjects and setting

The study consisted of 51 patients consecutively admitted to the ICU of the SCI Center of Werner Wicker Klinik in Bad Wildungen, Germany between October 1998 and July 2001. Patients were included in this study who presented with acute cervical spinal cord lesion due to injury or disease and with respiratory insufficiency requiring monitoring of circulation and respiration. We considered those cases as acute in which the time between onset of tetraplegia and admission to our hospital was no longer than 3 months. These patients were examined by FEES after obtaining an informed consent. FEES was performed and evaluated by the same individual (CW) throughout the duration of the study. In subjects ventilated by naso- or oratracheal tube FEES was performed after extubation when weaning was successful within 3 weeks after intubation or after tracheotomy in those with prolonged need of artificial respiration. Each subject was medically screened prior to FEES. This included: physical examination, motor/sensory neurological assessment according to ASIA,24 blood gas analysis, blood chemistry and X-ray of the chest and ultrasound of the diaphragm in order to detect phrenic nerve palsy.

The exclusion criteria consisted of MRSA colonization of the respiratory tract, fractures of the facial bones, recent surgery of nasal sinus, dependence on inotropes, in order to avoid dissemination of bacteria, disturbance of fracture healing or a risk of cardiac failure as a result of stimulation of the vagal nerve.

Data collection

The medical records were abstracted for the following information: ASIA score, cranial nerve palsy, age, gender, cause of spinal cord impairment, history of anterior-approach cervical spinal surgery, need for artificial respiration, tracheotomy, feeding via nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), phrenic nerve palsy.

Statistic evaluation

Statistics were performed to evaluate whether there is a statistically significant relation between level of dysphagia and age, respectively, level of CSCI. As the level of dysphagia is a variable measured on an ordinal scale, a calculation of a nonparametric correlation was performed (Spearman). The result lies within a range between −1 and +1. A result close to +1 stands for a strong, a result close to 0 for a weak relation. A negative result accounts for a reciprocal correlation.

FEES

FEES was performed with a flexible laryngoscope (Fa Rpszene, using Fa.Olympus endoscope, Hamburg, Germany). The ongoing examination was transmitted to a video screen. The setting allowed for a video documentation of the whole examination and selection of screen shots afterwards.

In patients with tracheotomy, the first examination was conducted with cuffed canula. The subsequent tests were done with cuffed or decuffed canula according to the patient's recovery. The endoscope was introduced via the nasal cavity. The epiglottis, vocal cords, arytenoid cartilages and sinus piriformis were examined with regard to the presence of edema, symmetrical motion of the vocal cords, retention, penetration or aspiration of saliva. Then white yoghurt was offered. The oral phase was observed with respect to apraxia. After initiation of the swallowing reflex, the presence of predeglutitive aspiration, retentions, penetration or aspiration of yoghurt was noticed. In case of aspiration, presence or absence of a sufficient coughing reflex were observed. The examination was stopped at this stage in patients with major aspiration in order to protect the lung. Patients with no or minor aspiration were offered a drink of methylene blue stained water. Again, presence of retentions and aspiration were observed. In patients with tracheotomy, suction was employed after the removal of the endoscope in order to detect residue of yoghurt or stained water in the tracheal secretion. The findings were recorded in a standard protocol.

Evaluation of the FEES protocols

The FEES protocols were evaluated with a focus on mastication, sensory perception, function of vocal cords, initiation of a swallowing reflex, presence of retention and aspiration and coughing reflex. Five levels of impairment of laryngeal function could be distinguished. They represented the prevalence and severity of dysphagia.

Level 1 presented with a complete laryngeal dysfunction. Mastication and sensory perception were grossly impaired. A generalized laryngeal edema was found. Due to a lacking or grossly insufficient swallowing reflex massive residue of saliva was found. This led to massive aspiration of saliva and food. As the coughing reflex was also lacking, the bronchial system could not be cleared.

In level 2 laryngeal function was severely impaired, though mastication and sensory perception were slightly improved. The swallowing reflex could be employed voluntarily, though impaired and at an insufficient frequency. Severe residue and aspiration of saliva, creamy food and liquids together with an impaired coughing reflex were present.

In level 3 we found a moderate impairment of laryngeal function. Mastication was improved, the swallowing reflex readily occurred. Mild or no residue or aspiration of saliva could be detected. Moderate residue and aspiration of creamy food and/or liquids was observed. The coughing reflex was readily employed to clear the trachea.

Level 4 comprised of a mild laryngeal dysfunction. Mastication, sensory perception and swallowing reflex were normal. Mild or no residue of saliva, creamy food and liquids were found. No aspiration of creamy food could be detected, whereas mild aspiration of saliva or liquids did occur. The coughing reflex was readily employed and sufficient. Together with the aspiration or as single feature, a moderate laryngeal edema could be seen.

Level 5 showed an unimpaired laryngeal function. No residue or aspiration of any kind could be detected. Mastication, swallowing reflex, sensory perception, movement of the vocal cords was normal, laryngeal edema absent.

Optional features at levels 1–4 consisted of an unilateral paralysis of a vocal cord, a dislocation of the arytenoid cartilages or a lesion of the mucous membrane of the vocal cord.

Guiding principles of treatment

Dependent on the observed level of dysphagia, each patient was subjected to a certain course of treatment. Special attention was paid to the individual needs of each patient with respect to his case history and side disorders.

Level 1: Artificial respiration, positive endexpiratory pressure (PEEP), FiO2>0.21, tracheotomy, cuffed tracheal tube, feeding only via nasogastral tube or PEG, speech therapy by basic stimulation and functional dysphagia treatment (FDT).

Level 2: Artificial respiration, PEEP, commencement of weaning in case of traceable diaphragm action, cuffed tracheal tube, nutrition only via PEG or nasogastric tube, Speech and dysphagia treatment.

Level 3: Permanent artificial respiration or weaning until partial or complete spontaneous breathing ability is obtained, tracheal tube decuffed for phonation training, cuffed for oral feeding. Oral diet with soft food and thickened liquids. FDT with focus on compensatory swallowing techniques, stimulation of coughing reflex.

Level 4: Permanent artificial respiration or weaning, tracheotomy tube decuffed. At completion of weaning, closure of tracheotomy. Phonation and gradual increase of oral diet, liquids thickened, then normal. Removal of PEG.

Level 5: Permanent artificial respiration or physiological breathing, regular oral diet, breathing exercises.

Results

Patient characteristics

The study sample comprised 51 individuals. Eight patients were excluded from the study. Exclusion criteria were colonization with MRSA in one patient, fractures of the skull in three and dependence on inotropes in four individuals. The four patients with cardiac instability died. The age of the subjects averaged 43.4 years, varying from 16 to 89 years. No statistically significant correlation between age and level of dysphagia could be detected neither on admission nor after treatment (Table 1). In all, 35 patients were male and 16 were female. Three of the patients died in the course of the study, two of them of lung embolism and one of cardiac failure.

Table 2 shows their allocation regarding the ASIA classification. The lesions of the spinal cord were caused by an accident in 46 patients and in five patients due to a disease or a circulatory disorder of the spinal cord. In 39 patients, anterior-approach spinal surgery had been performed. The motor levels at admission are given in Table 3.

Association of CSCI and dysphagia

FEES was performed in the 51 individuals with CSCI breathing physiologically or as soon as the oro- or nasotracheal tube could be removed or replaced by tracheotomy. At admission 21 individuals of the sample suffered from severe dysphagia with major aspiration (levels 1–3), 20 presented with mild dysphagia with the leading symptom of either laryngeal edema or mild aspiration with sufficient coughing reflex. No dysphagia could be detected in 10 patients. Other disorders detected included one subglottic stenosis of the trachea with fixed vocal cords, one postoperative unilateral vocal cord palsy and two luxations of an arytenoid cartilage. A closer look at the charts of 13 patients presenting with dysphagia levels 1 and 2 at admission revealed an impairment of lower cranial nerves in three patients and a reduced level of consciousness in five patients as a sign of an accompanying intracerebral impairment. In two patients suffering from ankylosing spondylitis the recovery was delayed.

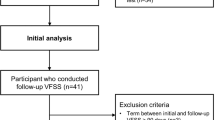

In the course of the study, 27 out of 51 patients were followed up by repeated FEES at intervals of 4–6 weeks. These patients had presented with aspiration as the main symptom in the initial FEES. This applied to all patients in levels 1–3 groups and to the patients with proof of aspiration in level 4 group. Including the 51 examinations at admission a total of 117 FEESs were performed, with a minimum of one examination and a maximum of nine per patient. In the course of the treatment, only three patients retained severe dysphagia with danger of substantial aspiration. One patient with remaining dysphagia level 2 expressed a cranial nerve palsy due to a brain-stem lesion. As shown in Table 4, no statistically significant relation between the level of SCI and the level of dysphagia could be detected at admission. At outcome there is a slight, but highly significant relation between these parameters. After treatment, patients with a higher level of SCI are more likely to express a higher level of dysphagia either.

Table 5 shows the mode of respiration at admission and after completion of the treatment. At admission, 37 patients were dependent on artificial respiration. In all, 11 of them were ventilated via a naso- or orotracheal tube, 26 via a tracheotomy. Of the patients, 14 breathed spontaneously throughout 24 h per day, three of them via tracheotomy. This makes for 29 patients carrying an tracheotomy tube. Only 11 patients breathed physiologically. After treatment, eight patients remained dependent on artificial respiration. Out of those, three patients could breathe spontaneously for a certain period of time. All of the five patients still requiring full-time artificial respiration showed motor level C2. In all, 40 patients were able to breathe spontaneously full time, 10 of them via tracheotomy, the other 30 physiologically.

At admission, 20 patients showed a neurological level of C2 with dependence on artificial respiration. In the course of the treatment 10 patients expressed a bilateral phrenic nerve palsy. Five out of this group remained completely dependent on artificial respiration, three could breathe spontaneously for a certain time of the day, in two full weaning was successful. One of these patients died. In five patients the phrenic nerve recovered unilaterally, in five others it recovered completely. In all of those 10 individuals weaning was completely successful. In summary, five out of 20 patients remained fully dependent on artificial respiration, three regained their ability to breathe partly and 11 completely, one died.

In Table 6 the development of the way of nutrition in the course of treatment is presented. On admission, 40 patients were fed exclusively via nasogastral tube or PEG. After therapy, 40 individuals were on a completely oral diet. Eight patients still carried a PEG tube. Only one patient was still fully dependent on feeding via PEG tube. He presented with a remaining dysphagia level 2. Seven patients were on a partly oral diet. Two of them were still identified as level 3 dysphagia. In five of the cases, in the absence of dysphagia, the amount of the oral diet had to be supplemented.

Discussion

This study examined the dysphagia in patients with CSCI consecutively admitted to the ICU of our SCI center because of respiratory insufficiency over a period of 34 months. To detect the prevalence and severity of dysphagia, the patients were examined by FEES. Relevant data were obtained from the patient's medical records. Patients showing aspiration as the leading symptom of dysphagia were included in a follow-up group and examined repeatedly by FEES. Data from the FEES protocols and the medical records were summarized to evaluate the outcome regarding the way of feeding and the need of artificial respiration.

In our study population of 51 patients 21 suffered from severe dysphagia with major aspiration, 20 presented with mild dysphagia either with discrete aspiration or laryngeal edema. Only 10 of the patients showed no signs of dysphagia at all. After completion of the treatment according to the guidelines given above, only three patients remained with a severe dysphagia, one at level 2 and two at level 3. Only the one patient with level 2 was still fully dependent on a PEG. In this patient a brain-stem injury with cranial nerve palsy had been verified. Seven other patients still carried a PEG. In five the nutrition had to be supplemented, because the amount of the oral diet was not sufficient, although aspiration was absent. Two others still presented with dysphagia level 3. As far as age is concerned, no statistically significant relation to the level of dysphagia could be detected, neither at admission nor after therapy. Comparing the level of dysphagia to the neurological level, no statistically significant relation between level of dysphagia and level of SCI could be detected at admission. After therapy, patients with a higher level of SCI were slightly, but statistically significant more likely to express a higher level of dysphagia. Regarding respiratory insufficiency, at admission, 37 of the group were dependent on artificial respiration. Eight patients remained dependent on artificial respiration, all of which had a motor level of C2. Out of those, three patients could breathe spontaneously for a certain period of time. Two patients with bilateral phrenic nerve palsy were able to breathe spontaneously throughout 24 h per day by means of their accessory breathing muscles.

It remains unclear, whether the need for tracheotomy is the reason for or the consequence of dysphagia. In only eight out of 46 patients suffering from CSCI following an accident no anterior approach spinal surgery was performed. In none of these patients severe dysphagia could be detected. But looking at the primary X-ray examinations of these patients, it has to be stated that patients stabilized via a posterior approach or treated conservatively, did not show the same extent of damage to the bone and luxation of the vertebral bodies than those with the anterior approach. So it cannot be determined, whether the anterior approach is a predictor of dysphagia or a sign of a more substantial injury of the spinal cord.

In our sample all of the three patients with cranial nerve lesions too presented with severe dysphagia. At admission five other patients with severe dysphagia had a reduced level of consciousness. As the CT or MRI scans of the brain showed no or minimal lesions, this mental state might be have been caused by general hypoxia.

Conclusions

Dysphagia could be identified in a substantial number of patients with acute CSCI admitted to the ICU of our center because of respiratory insufficiency. In addition to a laryngeal edema, aspiration was the main feature of dysphagia. This puts the patient at risk to develop aspiration pneumonia. FEES provided an easily applicable tool in the diagnosis of dysphagia and in the evaluation of therapeutic measures in an ICU setting. Dysphagia had a favorable prognosis in these patients, when treated early and consequently. By avoiding pulmonary complications, all patients with a motor level sub-C4 and below could terminate their weaning successfully. In the patients presenting with motor level sub-C2 only five out of initially 20 individuals remained completely dependent on artificial respiration. In all others, weaning was successful to the point of full or partial ability to breathe spontaneously. After treatment, all but one patient could take their nutrition partly or fully on an oral base. Our data suggest that patients suffering from brain-stem lesions or ankylosing spondylitis in addition to the SCI are prone to develop dysphagia. Further attention has to be given to dysphagia in patients with CSCI in order to prevent pulmonary complications and to improve their quality of live concerning nutrition and communication.

References

Hamdy S et al. The cortical topography of human swallowing musculature in health and disease. Nat Med 1996; 2: 1217–1224.

Kellow JE . Mastication and swallowing. In: Greger R, Windhorst U (eds). Comprehensive Human Physiology, Vol. 2. Springer: Heidelberg 1996, pp 1233–1237.

Goldenberg G . The neurology of swallowing. Sprache-Stimme-Gehör 1999; 23: 8–10.

Denk D-M, Swoboda H, Steiner E . Physiology of the larynx. Radiologe 1998; 38: 63–70.

Jahnke V . Differential diagnosis of dysphagia. HNO 1993; 41: 321–329.

Griggs CA, Jones PM, Lee RE . Videofluoroscopic investigation of feeding disorders of children with multiple handicap. Dev Med Child Neurol 1989; 31: 303–308.

Wuttge-Hannig A, Hannig C . Radiological differential diagnosis of neurological dysphagia. Radiologe 1995; 35: 733–740.

Grundy DJ, McSweeney T, Jones HW . Cranial nerve palsy in cervical injuries. Spine 1984; 9: 339–343.

Hannig C, Wuttge-Hannig A, Hess U . Analysis and radiological staging of the type and degree of severity in aspiration. Radiologe 1995; 35: 741–746.

Oursin C, Trabucco P, Bongartz G, Steinbrich W . Dysphagia following tumour surgery in the oral cavity and hypopharynx — an analysis by videofluoroscopy. Radiologe 1998; 38: 117–121.

Schurr MJ et al. Formal swallowing evaluation and therapy after traumatic brain injury improves dysphagia outcomes. J Trauma 1999; 46: 817–821.

Perry L, Love CP . Screening for dysphagia and aspiration in acute stroke: a systematic review. Dysphagia 2001; 16: 7–18.

Penington GR . Severe complications following ‘barium swallow’ investigation for dysphagia. Med J Aust 1993; 159: 764–765.

Doggett DL et al. Prevention of pneumonia in elderly stroke patients by systematic diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia: an evidence-based comprehensive analysis of the literature. Dysphagia 2002; 16: 279–295.

Hoppers P, Holm SE . The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in dysphagia rehabilitation. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1999; 14: 475–485.

Leder SB . Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in patients with acute traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1999; 14: 448–453.

Staff DM, Shaker R . Videoendoscopic evaluation of supraesophageal dysphagia. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2001; 3: 200–205.

Winslow CP, Winslow TJ, Wax MK . Dysphonia and dysphagia following the anterior approach to the cervical spine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001; 127: 51–55.

Stewart M, Johnston RA, Stewart I, Wilson JA . Swallowing performance following anterior cervical spine surgery. Br J Neurosurg 1995; 9: 605–609.

Macdonald RL et al. Multilevel anterior cervical corpectomy and fibular allograft fusion for cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg 1997; 86: 990–997.

Brown JA . Cervical stabilisation by plate and bone fusion. Spine 1988; 13: 236–240.

Morpeth JF, Williams MF . Vocal fold paralysis after anterior cervical discectomy fusion. Laryngoscope 2000; 110: 43–46.

Kirshblum S et al. Predictors of dysphagia after spinal cord injury. Arch Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1101–1105.

Maynard FM et al. International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 266–274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolf, C., Meiners, T. Dysphagia in patients with acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 41, 347–353 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101440

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101440

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Acute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury: A Literature Review

Dysphagia (2023)

-

The time course of dysphagia following traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: a prospective cohort study

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Oropharyngeal dysphagia management in cervical spinal cord injury patients: an exploratory survey of variations to care across specialised and non-specialised units

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

Traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: recovery of penetration/aspiration and functional feeding outcome

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Risk factors for dysphagia after a spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Spinal Cord (2018)