Abstract

Reduced brain serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine: 5-HT) transporter activity has been associated with susceptibility to various forms of psychopathology, including bulimia nervosa (BN) and related syndromes characterized by appetitive or behavioural dysregulation. We applied density (Bmax) of platelet [3H-]paroxetine binding as a proxy for central 5-HT reuptake activity in two groups of women (33 with BN-spectrum disorders and 19 with no apparent eating or psychiatric disorders), most of these individuals' mothers (31 and 18, respectively), and a small sampling of their sisters (seven and eight, respectively). Hierarchical linear modeling techniques were used to account for nesting of individuals within families and diagnostic groupings. Bulimic probands, their mothers, and their sisters all displayed significantly lower density (Bmax) of platelet-paroxetine binding than did ‘control’ probands, mothers, or sisters—even when relatives showing apparent eating or psychiatric disturbances were excluded. In addition, in bulimic probands and mothers, significant within-family correlations were obtained on Bmax. These findings imply a heritable trait (or endophenotype), linked to 5-HT activity, and carried by BN sufferers and their first-degree relatives (even when asymptomatic). We propose that, under conducive circumstances, such a trait may increase risk of binge-eating behavior, or associated symptoms of affective or behavioral dysregulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Active bulimia nervosa (BN) sufferers display altered serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine: 5-HT) system activity, as evinced by reduced platelet binding of 5-HT reuptake inhibitors (Marazziti et al, 1988; Steiger et al, 2000, 2001), central 5-HT transporter availability (Tauscher et al, 2001), neuroendocrine responses to 5-HT precursors and 5-HT agonists/partial agonists (Levitan et al, 1997; Steiger et al, 2001), and (in high-frequency bingers) cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) (Jimerson et al, 1992). As calorie deprivation produces measurable alterations of endocrine responses after 5-HT stimulation in humans (Cowen et al, 1996) and of 5-HT transporter activity in animals (Huether et al, 1997), intermittent caloric restraint (characteristic of active bulimics) might contribute to altered 5-HT status in BN.

Reduced 5-HT activity in bulimic syndromes could, however, also correspond to a primary vulnerability, arising independently of disordered eating. Favoring this view, in bulimic populations, correspondences are noted between variations on ‘trait’ dimensions (like impulsivity, compulsivity, or perfectionism) and indices bearing upon 5-HT activity—including density of platelet paroxetine binding (Steiger et al, 2001, 2004), platelet monoamine oxidase concentrations (Carrasco et al, 2000), and 5-HT-stimulated neuroendocrine responses (Steiger et al, 2001; Waller et al, 1996). In addition, studies in BN sufferers have linked variants of the 5-HT transporter promoter polymorphism, 5HTTLPR (Steiger et al, 2005a) and the 5-HT2a promoter polymorphism, −1438G/A (Nishiguchi et al, 2001; Bruce et al, 2005), with anomalous 5-HT activity and extremes of impulsivity and/or affective instability. Further corroborating a trait-oriented view, studies in long-term recovered ‘binge-eaters’ (individuals with BN or Anorexia Nervosa-Binge/Purge Subtype) reveal persistent 5-HT anomalies—including reduced 5-HT2a receptor activity (Bailer et al, 2004; Kaye et al, 2001), hyper-sensitivity to effects of acute tryptophan depletion (Smith et al, 1999), abnormal CSF 5-HIAA (Kaye et al, 1998), and reduced platelet paroxetine binding (Steiger et al, 2005b).

Several observations suggest that platelet 5-HT reuptake models at least some aspects of central 5-HT transporter activity: human platelet and brain 5-HT transporters show morphological and pharmacokinetic resemblances (Lesch et al, 1993), and appear to have common genetic determinants (Nobile et al, 1999). In addition, studies on depression show 5-HT reuptake to be reduced in blood platelets (Ellis and Salmond, 1994) and in post-mortem brain tissues (Mann et al, 2000). More recently, 5-HT transporter activity in human platelets has been shown to correspond to transporter activity in brain synaptosomes (Rausch et al, 2005). Similar correspondences between platelet and central 5-HT indices have been noted in bulimic populations. Studies using platelet [3H-]imipramine (Marazziti et al, 1988) or [3H-]paroxetine (Steiger et al, 2000, 2004) binding have shown marked reductions in peripheral 5-HT transport density (Bmax), whereas single photon emission computed tomography confirms reduced central 5-HT transporter availability (Tauscher et al, 2001).

In bulimic women, one study has shown a correspondence between [3H-]paroxetine-binding findings and variations in a polymorphism encoding brain 5-HT transporter protein (Steiger et al, 2005a). No study has as yet examined whether or not familial tendencies (compatible with a hereditary ‘trait’) exist on 5-HT indices among relatives of eating-disorder sufferers. However, suggesting that this may be true of other psychopathological syndromes, unaffected relatives of obsessive–compulsive disorder (Delorme et al, 2005) and manic-depressive (Leboyer et al, 1999) patients are reported to have reduced platelet 5-HT reuptake. The present study explored the possibility that mothers and sisters of bulimic probands (even when free of eating or psychiatric symptoms) might evince reduced platelet 5-HT reuptake activity, compared to relatives of normal-eater controls. (We studied females, not because of gender-based hypotheses, but because a concurrent recruitment emphasized proband–mother–sister triads and pairs.) Likewise, we hypothesized that bulimic women and their first-degree relatives might both evince more 5-HT linked, ‘spectrum’ disturbances (eg depression) over their lifetimes.

METHODS

Participants

This study received institutional ethics-board approval, and involved participation by informed consent. Structured interviews (described below) were used to establish current and lifetime eating and psychiatric symptoms and disorders in bulimic and healthy-control participants and their relatives.

Bulimic Probands

BN-spectrum participants were recruited through a specialized Eating Disorders (ED) program. We completed assays in 33 women (aged 17–45 years), 18 (54.5%) of whom had met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for BN-Purging subtype, and 15 (45.5%) for a bulimia-spectrum EDNOS (in which bulimic symptoms occurred at subthreshold levels or, in one case, in whom there were no compensatory behaviors after eating binges). As distinctions between ‘threshold’ and ‘subthreshold’ BN (Fairburn and Harrison, 2003) or ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ bingers (Pratt et al, 1998) appear to be artificial, we regarded this sample as representative of clinically observed ‘bulimia-spectrum syndromes’. Mean age and body mass index (BMI: kg/m2) in our sample were 24.9 (±6.0) and 22.9 years (±4.8) kg/m2, respectively.

Comparison Probands

To approximate the student/non-student ratio among our clinical participants, 19 healthy women, aged 19–45 years (mean age=24.5±6.3 years; mean BMI=21.6±2.9 kg/m2), were recruited through university classes or newspaper advertisements. Candidates passed an initial structured telephone screening (designed for this study) that assessed past or present EDs, periods of intense weight concerns or marked intentional weight loss, binge eating, purging, medical problems, active mental-health problems (eg depression, anxiety, substance abuse) and treatments, pregnancy, lactation, and menstrual status. Further evaluation for psychopathology was conducted with structured diagnostic interviews, as described below. In five of the bulimic cases, interviews revealed remission of binge-purge symptoms by the time of testing. Given that reduced paroxetine binding in BN sufferers is already well-established (Steiger et al, 2000, 2001, 2004), that low platelet-paroxetine binding has been observed even after long-term remission of symptoms in former bulimics (Steiger et al, 2005b), and that our main interest was in findings in bulimics' relatives, we kept the ‘remitted’ cases. Nonetheless, a t-test for differences between active and remitted patients on paroxetine binding indicated that the remitted patients biased (if anything) against the expected finding of reduced paroxetine binding in bulimic probands. In addition, upon interview, one control proband showed post-traumatic stress disorder (following a diagnosis of breast cancer), but normal-range paroxetine binding. Deletion of the subject in question at later analytic tiers (see Results) did not alter findings concerning bulimic vs control differences. Given principle interest in data from relatives, this subject was retained to avoid exclusion of her mother from analyses.

First-Degree Relatives

All participants recruited either a mother or a sister. A total of 49 probands (31 eating-disordered and 18 normal-eater) implicated their mothers, and 14 (seven eating-disordered and seven normal-eater) recruited a sister (with one control proband recruiting two sisters). Mean ages (years) (±SD) of these relatives were: bingers' mothers=52.2 (±5.7); controls' mothers=53.6 (±9.1); bingers' sisters=26.9 (±5.5); controls' sisters=21.3 (±2.5). Mean BMIs (kg/m2) (±SD) of these relatives were: bingers' mothers=26.0 (±6.9); controls' mothers=24.9 (±5.0); bingers' sisters=23.2 (±4.2); controls' sisters=23.0 (±4.1).

Measures

ED symptoms

We generally assessed ED symptoms using the Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) interview (Fairburn and Cooper, 1993). In three control relatives (one mother and two sisters), it was not possible to conduct face-to-face EDE interviews and instead, ED diagnoses were established using the EDE-Q questionnaire (Fairburn and Beglin, 1994). The EDE-Q, a 36-item self-report measure adapted from the EDE interview, yields the same four subscales as does the EDE, on the same 7-point scale. We also used the well-known Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) (Garner et al, 1982) to measure ED attitudes and behaviors (EAT-26 scores corroborated all diagnostic inferences drawn with the EDE-Q). To reflect nutritional status, we computed BMI.

Generalized psychopathological characteristics were assessed using: the Barrat Impulsivity Scale (BIS) (Patton et al, 1995), selected subscales from the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ) (Livesley et al, 1992), tapping such traits as Compulsivity, Sensation Seeking, and Affective Instability; and the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Weissman et al, 1977). Details on psychometric adequacy of the scales employed are provided elsewhere (Steiger et al, 2000, 2001, 2004).

Axis-I comorbidity

In most cases, Axis-I screening was accomplished using a computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV (DIS4) (Bucholz et al, 1991) to guide face-to-face clinical interviews. However, given a shift in study protocols, five proband recruits instead completed the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I (SCID-I, Outpatient version: First et al, 1997), and the Clinician-Administered Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS: Weathers et al, 2001). DIS4 and SCID-I are ‘industry standard’ assessments for Axis-I syndromes. Similarly, the CAPS is a standard criterion measure of PTSD, exhibiting excellent convergent and discriminant validity, and excellent reliability. Impact of scale differences was buffered by the fact that DIS4, SCID-I, and CAPS interviews all provide valid, reliable diagnostic determinations. We did, nonetheless, evaluate agreement for DIS4 and SCID-I diagnoses for a related study, by forcing data from 50 DIS4 interviews (half for bulimic, half for nonbulimic women) into the SCID-I coding scheme. Resulting kappas (and percent agreements) for past 12-month presence of major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder ranged from 0.84 (94%) to 1.00 (100%)—indicating excellent agreement. Given incompatibilities among items, a comparable translation of DIS4 and CAPS diagnoses was not feasible.

5-HT measures

Neurobiological assays were performed under blind conditions in a lab run by Dr Ng Ying Kin. Participants were asked to refrain from cigarettes and coffee on the day of testing. We did not treat oral contraceptive use as an exclusion criterion, but did take steps to control for potential effects on paroxetine binding. Similarly, during statistical analyses, we took care to remove any relatives who were taking 5-HT active medications. Given main interest in findings in relatives, and several previous reports confirming reduced platelet-paroxetine binding in bulimic subjects regardless of medication status (Steiger et al, 2000, 2001, 2004), we did not remove 16 bulimic cases who were taking serotonergic medications at the time of testing. We did, however, test for medication effects, to rule out the possibility that differences in mean paroxetine binding obtained in bulimic and nonbulimic proband groups might have been influenced by confounding effects of medication. No potential confounds were identified (see Results). Detailed procedures for sampling blood and determining [3H-]paroxetine binding Bmax (measured as fmol/mg protein) have been provided elsewhere (Steiger et al, 2000, 2001, 2004).

We took various steps to control influences upon density of paroxetine binding due to season of testing (Spigset et al, 1998) and use of hormonal contraceptives or 5-HT active medications. To control for possible seasonal effects, we repeated all hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) analyses conducted on paroxetine-binding Bmax, but using ‘dummy codes’ to first control for variance attributable to testing during Spring, Summer, Winter, or Fall. All differences owing to the bulimic/nonbulimic distinction still emerged at the 0.001 level (or better). Similarly, for contraceptive use, we repeated all HLM analyses assessing group effects on paroxetine binding, but applying a dichotomous variable reflecting contraceptive use as a covariate. Again, results remained identical to those reported in the text.

RESULTS

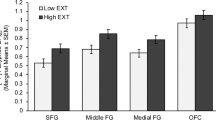

Figure 1 presents scatter plots of actual paroxetine-binding density (Bmax) values obtained in control and bulimic probands, and in corresponding mother and sister samples. Mean (±standard deviation) values obtained were as follows: control probands (n=19)=1225.11 (±456.42), bulimic probands (n=33)=586.39 (±260.49), controls' mothers (n=18)=1237.11 (±478.53), bulimics' mothers (n=31)=629.39 (±263.75), controls' sisters (n=8)=1130.63 (±496.02), and bulimics' sisters (n=7)=384.57 (±161.74). To isolate any potential confounds owing to effects of 5-HT active medications, we compared mean Bmax values obtained in medicated (534.63±182.60; n=16) and unmedicated (635.12±315.04; n=17) bulimic women—finding no difference (t (31)=−1.11, p=0.275). Given the unbalanced, hierarchically structured nature of our data set (individuals being nested within families, which are in turn ascribed to different diagnostic groupings), and dependencies resulting from the clustering of participants' within-family units, conventional statistical techniques were not well suited. Instead, hypotheses pertaining to family- and diagnosis-based variations were tested using HLM (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002) techniques. HLM represents an extension of the general linear model used in traditional regression, but provides an ideal option for analysis of unbalanced, hierarchically structured data sets. Furthermore, rather than assuming independent sampling, HLM enables testing of degree of dependency resulting from such factors as family membership. The general form of the analyses in question was:

where Yij refers to the estimated value of the outcome variable for the ith person in the jth family; D_Proband is a dummy variable taking on a value of 1 if the participant is a proband and 0 otherwise; D_Relative is a dummy variable taking on a value of 1 if the participant is a relative and 0 otherwise; D_ED is a dummy variable taking on a value of 1 if the family includes an eating-disordered proband and 0 otherwise.

Given disparate ns for mother and sister samples, we analyzed ‘mother’ and ‘sister’ data sets separately. The first analysis examined data for paroxetine-binding density (Bmax) in all 31 bulimic and 18 normal-eater proband–mother pairs (ie 98 individuals). In this analysis, the intraclass correlation (ICC), estimating the proportion of variability in Bmax values attributable to between- rather than within-family effects, and thought in such contexts to estimate heritability (Spigset et al, 1998), was 0.652. Given 65.2% of variance owing to between-family effects, familial aggregation was clearly indicated. To further explore familial tendencies, we estimated a multilevel model that took into account family membership, affiliation with a bulimic or normal-control proband, and being a proband or mother. Results showed bulimic probands to have expectedly (and significantly) lower levels of Bmax compared to control probands (see Tables 1a and 2). More importantly, bulimics' mothers also had significantly lower levels of Bmax than did mothers of control probands.

Subsequently, to control for possible effects of having an ED diathesis or recently active psychopathology, we repeated the analysis, but this time removing any proband–mother pairs in which a mother had reported a lifetime history of ED, or past 12 months history of Axis-I disorders (major depression, obsessive–compulsive disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder), or for whom (as occurred in isolated cases) missing data prevented confirmation of the psychiatric history. This step resulted in removal of 11 mothers of bulimic probands (one with anorexia nervosa, one an EDNOS in the restricter spectrum, one a bulimia-spectrum EDNOS with concurrent anxiety disorders and depression, one with simple phobia and major depression, two with panic disorders, two with post traumatic stress disorders, two with major depression alone, and one with missing data) and five control mothers (one with PTSD, one with major depression, one with an EDNOS, and two with missing DIS4 data). The new analysis, based on 20 bulimic and 13 healthy-control pairs, or 66 individuals (see Tables 1b and 2), still indicated bulimic probands and mothers to have significantly lower paroxetine binding than did control probands and mothers.

All effects of interest remained in a third analytic tier, performed after removal of two additional bulimics' mothers and three controls' mothers who indicated use of 5-HT active medications (but who had not yet been eliminated due to lifetime ED or past 12-month psychopathology). This final analysis implicated 56 individuals from 28 families (18 bulimics and 10 controls).

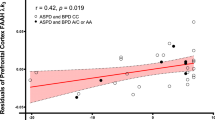

As a next step, we computed correlations representing proband–mother associations within bulimic and nonbulimic groups, for Bmax, and then for scale scores indicating impulsivity (BIS), depression (CES-D), and affective instability. Results revealed significant correlations for bulimic probands and mothers on paroxetine binding (r=0.49, n=31, p<0.01), but not on indices of affective instability (r=0.12, n=30, p=0.52), impulsivity (r=0.11, n=29, p=0.56), or CES-D depression (r=0.22, n=30, p=0.25). Among control probands and mothers, all corresponding correlations were nonsignificant (Bmax r=0.30, n=18, p=0.23; affective instability r=0.33, n=18, p=0.19; BIS r=0.03, n=17, p=0.91; and CES-D r=0.22, n=18, p=0.37). In control pairs, sample sizes may provide limited power for detecting existent relationships. However, findings in bulimic proband–mother pairs are consistent with reduced paroxetine binding, in the absence of increased current psychopathological symptoms in the mothers. As in previous analyses, to rule out contaminating effects attributable to an ED history or recent psychopathology, we repeated the analyses, this time eliminating pairs in which mothers reported the tendencies in question. Results still indicated a strong correlation between scores in bulimic probands and their mothers on Bmax (r=0.68, n=20, p<0.001), but not on affective instability (r=0.06, n=20, p=0.80), impulsivity (r=0.29, n=19, p=0.24), or depression (r=0.31, n=20, p=0.18); and not for control probands and mothers on Bmax (r=0.42, n=13, p=0.15), affective instability (r=0.15, n=13, p=0.62), impulsivity (r=−0.12, n=12, p=0.72), or depression (r=0.33, n=13, p=0.27). Scatter plots illustrating significant correlations obtained on paroxetine binding in bulimic probands and their mothers are shown in Figure 2.

Next, to evaluate the possibility that ‘subsyndromal’ clinical disturbances accounted for reduced paroxetine binding in bulimics' mothers, we performed parallel HLM analyses to those described above, but this time examining symptom scores for proband and mother groups on measures reflecting generalized eating symptoms (EAT-26), dieting (EAT-26 dieting subscale), depressed mood (CES-D), impulsivity (BIS), and (from the DAPP) affective instability, sensation seeking, compulsivity, restricted expression, anxiety, and self-harm. Estimated means and group comparisons resulting from these analyses (see Table 2) always showed elevated symptoms in bulimic vs nonbulimic probands, but revealed no differences between corresponding mother groups. In other words, despite their apparently reduced paroxetine binding, bulimics' mothers did not display increased psychopathological symptoms. Likewise, the bulimics' mothers showed no propensity towards dietary restraint. Identical results emerged in a later analytic tier (see Table 2), in which (as before) we removed any mothers showing a history of ED or past 12-month presence of other psychopathology. (given very small ns available for sister groups, we present no parallel analyses on psychopathological traits for bulimic and nonbulimic sisters).

Expecting that there would be elevated lifetime risk of psychopathology in bulimics and their relatives (even in the absence of current expressions in the relatives), we examined lifetime occurrence of EDs, affective disorders, and anxiety disorders, according to DIS4 (or in rare cases, SCID-I and CAPS) interviews in eating-disordered and noneating disordered probands and their mothers. Not surprisingly, results showed consistently elevated lifetime comorbidity in bulimic vs control probands—with rates for anorexia nervosa (40.6 vs 0.0%), BN (71.9 vs 0.0%), major depression (68.8 vs 21.1%), agoraphobia (31.3 vs 5.3%), post-traumatic stress disorder (31.3 vs 5.3%), and social phobia (43.8 vs 5.3%) always being significantly higher (p<0.04–p<0.001) in the bulimic group, according to χ2 or Fisher's exact tests (as appropriate, given frequencies obtained). Whereas bulimics' mothers showed no such widespread increase in comorbidity over that in control mothers, the bulimics' mothers did display significantly more frequent major depression (40.0 vs 12.5%, χ(1)2=4.10, p<0.05), and nonsignificantly higher rates of most other disorders examined. Limited power due to small sample sizes may explain absence of statistical effects in some instances.

Finally, we conducted a parallel HLM analysis to that performed for proband–mother pairs, but aimed at exploring differences between our seven bulimic and eight normal-eater sisters. Although the sample size asks for reserved interpretation, within the available sample the ICC (0.827) suggested a strong familial-aggregation tendency. Furthermore, we obtained reductions on paroxetine binding in bulimics sisters, relative to those obtained in nonbulimics' sisters, and comparable to those obtained in bulimic probands themselves (see Table 1c). (Given limited samples for sisters, we did not conduct a full set of analyses addressing presence of psychopathological traits or comorbidity.)

DISCUSSION

This study contributes various elements towards the modeling of the role of 5-HT mechanisms in bulimic syndromes. To start, our findings replicate previous ones showing that, compared to women who eat normally, women with bulimia-spectrum syndromes have substantially reduced density (Bmax) of platelet [3H-]paroxetine binding sites Steiger et al, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2005b). Given findings showing at least partial correspondences between peripheral and central 5-HT uptake indices (Rausch et al, 2005; Lesch et al, 1993; Tauscher et al, 2001), peripheral effects might be thought to serve as a proxy for the corresponding central processes.

Regardless of the anatomical generality of the observation, however, our findings with paroxetine binding provide strong (and intriguing) indications of a generality at the family level—as we observe systematic reductions in binding density among the mothers and sisters of individuals with bulimia-spectrum EDs (when compared to relatives of control participants)—even when analyses are constrained to relatives (ie mothers) showing absence of eating and psychiatric disturbances. Further corroborating the idea of familial transmission, results show strong intrafamilial (bulimic proband-bulimic mother) correlations on binding density, and ICCs reflecting strong within-family associations consistent with a heritable effect (Falconer and Mackay, 1996). (To the preceding, we add that maladaptive eating practices could have contributed to low 5-HT reuptake in our active bulimia sufferers, but are unlikely to explain reduced paroxetine binding in our bulimics' unaffected mothers and sisters—as the latter individuals showed no signs of being unusually diet prone, according to EAT-26 Dieting subscale scores.) All of the preceding argue that density of 5-HT reuptake sites is a transmissible familial propensity.

A possible indirect manifestation of the same effect may be that mothers of bulimic probands reported significantly more-frequent lifetime major depression than did control mothers, and (nonsignificantly) more eating and other psychiatric disorders—without, on average, displaying elevations on indices reflecting active eating or psychiatric symptoms (see Table 2). These trends are consistent with the notion that the mothers in question, although currently asymptomatic, carried a susceptibility to 5-HT dysregulation, and corresponding lifetime risk of developing 5-HT linked psychiatric disturbances (like major depression). In other words, we may be seeing manifestations of an underlying 5-HT-mediated ‘trait’, revealed by low platelet paroxetine binding, and by an intermittently (or situationally) expressed vulnerability to disturbed eating, depression (and related symptoms). (To the preceding, we add the caveat that limited statistical power, related to sample size, could be a factor underlying absence of differences between bulimic and healthy-control mothers on eating-symptom and psychopathological-trait measures shown in Table 2.) Supporting our contention that processes underlying such effects are hereditary, we have recently documented a correspondence between presence of the short (s) allele of the 5-HT transporter gene promoter (5HTTLPR) and reduction of platelet paroxetine binding in bulimic women (Steiger et al, 2005a). The s allele is believed to encode lesser transcription of the 5-HT transporter protein (Lesch et al, 1993), and should (logically) identify individuals in whom 5-HT transporter activity may generally be low, or alternatively, in whom there may exist potentials for situational reductions in transporter activity.

CONCLUSIONS

Results of this study need to be interpreted in light of several limiting factors: Samples are relatively small, and possible influences due to such factors as subject-based selection of participating relatives, or use of cigarettes, caffeine, or alcohol, are imperfectly controlled. Nonetheless, our findings do appear to link platelet paroxetine binding with a 5-HT-mediated ‘trait’, that exists in the context of vulnerability to the development of bulimic eating problems (and other psychopathological entities), but independently of active bulimia-spectrum manifestations. Such a ‘trait’, insofar as it is associated with risk of developing bulimic symptoms, but occurs ‘invisibly’ (ie in the absense of active clinical symptoms) in bulimics' unaffected relatives, meets criteria for what is often called an ‘endophenotype’—an intrinsic trait that may convey susceptibility to a particular phenotypic expression (Gottesman, 2003).

Paroxetine-binding results we obtain in bulimic women and their relatives are, furthermore, highly compatible with those obtained by other investigators in relatives of individuals suffering disorders as diverse as obsessive–compulsive disorder (Delorme et al, 2005) or manic-depressive illness (Leboyer et al, 1999). An obvious implication is that, if we are observing an ‘endophenotype’, it is not one that defines specific vulnerability to a bulimic syndrome, but rather a generalized risk (perhaps of syndromes characterized by breakdown of behavioral, affective, and/or appetitive controls). Such generality is of theoretical interest, as it would corroborate the existing notion that bulimic syndromes share causal processes with anxiety and affective disorders (see Fairburn and Harrison, 2003; Steiger, 2004). A specific factor, in the context of bulimic eating syndromes, might nonetheless be that cultural inducements to maintain thin appearance (and the consequent dieting that they encourage) can have adverse consequences upon 5-HT functioning in individuals who are constitutionally disposed towards low 5-HT transporter activity (Steiger, 2004).

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC.

Bailer UF, Price JC, Meltzer CC, Mathis CA, Frank GK, Weissfeld L et al (2004). Altered 5-HT (2A) receptor binding after recovery from bulimia type anorexia nervosa: relationships to harm avoidance and drive for thinness. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol: J Eur Coll Neuropsychopharmacol 29: 1143–1155.

Bruce KR, Steiger H, Joober R, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Israel M, Young SN (2005). Association of the promoter polymorphism-1438G/A of the 5-HT2A receptor gene with behavioural impulsiveness and serotonin function in women with bulimia nervosa. Am J Med Genet. Part B (Neuropsychiatr Genet) 137B: 40–44.

Bucholz KK, Robins LN, Shayka JJ, Przybeck TR, Heltzer JE, Goldring E et al (1991). Performance of two forms of a computer psychiatric screening interview: Version 1 of the DISSI. J Psychiatry Res 25: 117–129.

Carrasco JL, Diaz-Marsa M, Hollander E, Cesar J, Saiz-Ruiz J (2000). Decreased platelet monoamine oxidase activity in female bulimia nervosa. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol: J European Coll Neuropsychopharmacol 10: 113–117.

Cowen PJ, Clifford EM, Walsh AES, Williams C, Fairburn CG (1996). Moderate dieting causes 5-HT2C receptor supersensitivity. Psychol Med 26: 1155–1159.

Delorme R, Betancur C, Callebert J, Chabana N, Laplanche J-L, Mouren-Simeon M-C (2005). Platelet serotonergic markers as endophenotpyes for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 1539–1547.

Ellis PM, Salmond C (1994). Is platelet imipramine binding reduced in depression? A meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 36: 292–299.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eating Disord 16: 363–370.

Fairburn CG, Cooper P (1993). The eating disorders examination. In: Fairburn C, Wilson G (eds). Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment, 12th edn. Guilford: New York. pp 317–360.

Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ (2003). Eating disorders. Lancet 361: 407–416.

Falconer DS, Mackay TFC (1996). An Introduction to Quantitative Genetics, 4th edn. Prentice-all: Essex. pp 161–183.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams M, Janet BW, Benjamin L (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Research Version. Patient Edition. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York.

Garner DM, Olmsted M, Bohr Y, Garfinkel P (1982). The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12: 871–878.

Gottesman II (2003). The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry 160: 636–645.

Huether G, Zhou D, Schmidt S, Wiltfang J, Rüther E (1997). Long-term food restriction down regulates the density of serotonin transporters in the rat frontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry 41: 1174–1180.

Jimerson DC, Lesem MD, Kaye WH, Brewerton TD (1992). Low serotonin and dopamine metabolite concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid from bulimic patients with frequent binge episodes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49: 132–138.

Kaye WH, Frank GK, Meltzer CM, Price JC, McConaha CW, Crossan PJ et al (2001). Altered serotonin 2A receptor activity in women who have recovered from bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 158: 1152–1155.

Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Moss H, Fernstrom JD, Fernstrom MH, Lilenfeld LR et al (1998). Alterations in serotonin activity and psychiatric symptoms after recovery from bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55: 927–935.

Leboyer M, Quintin P, Manivet P, Varoquaux O, Allilaire J-F, Launay J-M (1999). Decreased serotonin treasnporter binding in unaffected relatives of manic depressive patients. Biol Psychiatry 46: 1703–1706.

Lesch KP, Wolozin BL, Murphy DL, Reiderer P (1993). Primary structure of the human platelet serotonin uptake site: identity with the brain serotonin transporter. J Neurochem 60: 2319–2322.

Levitan RD, Kaplan AS, Joffe RT, Levitt AJ, Brown GM (1997). Hormonal and subjective responses to intravenous meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 521–527.

Livesley WJ, Jackson DN, Schroeder ML (1992). Factorial structure of traits delineating personality disorders in clinical and general population samples. J Abnormal Psychol 101: 432–440.

Mann J, Huang Y, Underwood M, Kassir S, Oppenheinm S, Kelly T et al (2000). A serotonin trasnporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and prefrontal cortical binding in major depression and suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 729–738.

Marazziti D, Macchi E, Rotondo A, Placidi GF, Cassano GB (1988). Involvement of the serotonin system in bulimia. Life Sci 43: 2123–2126.

Nishiguchi N, Matsushita S, Suzuki K, Murayama M, Shirakawa O, Higuchi S (2001). Association between 5HT2A receptor gene promoter region polymorphism and eating disorders in Japanese patients. Biol Psychiatry 50: 123–128.

Nobile M, Begni B, Giorda R, Alessqandro F, Marino C, Molteni M et al (1999). Effects of serotonin transporter promoter genotype on platelet serotonin transporter functionality in depressed children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38: 1396–1402.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barrat ES (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol 51: 768–774.

Pratt EM, Niego SH, Agras SW (1998). Does the size of a binge matter? Int J Eating Disord 24: 307–312.

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd edn. Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Rausch J, Johnson ME, Li J, Hutcheson J, Carr BM, Corley KM et al (2005). Serotonin transport kinetics correlated between human platelets and brain synaprosomes. Psychopharamacology 180: 391–398.

Smith KA, Fairburn CG, Cowen PJ (1999). Symptomatic relapse in bulimia nervosa following acute tryptophan depletion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 171–176.

Spigset O, Allard P, Mjorndal T (1998). Circannual variations in the binding of [3H]lysergic diethylamide to serotonin2A receptors and of [3H]paroxetine to serotonin uptake sites in platelets from healthy volunteers. Biol Psychiatry 43: 774–780.

Steiger H (2004). Eating disorders and the serotonin connection: State, trait and developmental effects. J Psychiatry Neurosci: JPN 29: 20–29.

Steiger H, Gauvin L, Israël M, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Young SN, Roussin J (2004). Serotonin function, personality-trait variations and childhood abuse in women with bulimia-spectrum eating disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 830–837.

Steiger H, Joober R, Israël M, Young SN, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Gauvin L et al (2005a). The 5HTTLPR polymorphism, psychopathological symptoms, and platelet [3H-]paroxetine binding in bulimic syndromes. Int J Eating Disord 37: 57–60.

Steiger H, Koerner NM, Engleberg M, Israël M, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Young SN (2001). Self-destructiveness and serotonin function in bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Res 103: 15–26.

Steiger H, Leonard S, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Ladouceur C, Ramdoyal D, Young SN (2000). Childhood abuse and tritiated paroxetine binding in bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry 61: 428–435.

Steiger H, Richardson J, Israel M, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Bruce K, Mansour S et al (2005b). Reduced density of platelet binding sites for [3H-]paroxetine in remitted bulimic women. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 1028–1032.

Steiger H, Young SN, Kin NM, Koerner N, Israel M, Lageix P et al (2001). Implications of impulsive and affective symptoms for serotonin function in bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 31: 85–95.

Tauscher J, Pirker W, Willeit M, de Zwaan M, Bailer U, Neumeister A et al (2001). Beta-CIT and single photon emission computer tomography reveal reduced brain serotonin transporter availability in bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry 49: 326–332.

Waller DA, Sheinberg AL, Gullion C, Moeller FG, Cannon DS, Petty F et al (1996). Impulsivity and neuroendocrine response to buspirone in bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry 39: 371–374.

Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT (2001). Clinician-administered PTSD scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depression Anxiety 13: 132–156.

Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ (1977). Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 106: 203–214.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grant no. SR-4306, awarded to Drs Steiger and Joober by the Quebec government's Joint CQRS-FRSQ-MSSS Program in Mental Health. Preliminary results from this study were presented at annual meetings of the Eating Disorders Research Society, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, October 9, 2004, and the Academy for Eating Disorders International Conference on Eating Disorders, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, April 29, 2005.

We thank Melanie Aubut, Andrea Byrne, Leechen Faarkas, Julia Finkelstein, Debra Gartenberg, Jasmine Joncas, Stephanie Levine-Grant, Sandra Mansour, and Heidi Shapiro for their contributions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steiger, H., Gauvin, L., Joober, R. et al. Intrafamilial Correspondences on Platelet [3H-]Paroxetine-Binding Indices in Bulimic Probands and their Unaffected First-Degree Relatives. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 1785–1792 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301011

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301011

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serotonin transporter binding after recovery from eating disorders

Psychopharmacology (2008)