Abstract

A polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1, 10-repeat) is associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and has been linked to an enhanced response to methylphenidate (MPH). One aspect of the attention deficit in ADHD includes a subtle inattention to left space, resembling that seen after right cerebral hemisphere damage. Since left-sided inattention in ADHD may resolve when treated with MPH, we asked whether left-sided inattention in ADHD was related to DAT1 genotype and the therapeutic efficacy of MPH. A total of 43 ADHD children and their parents were genotyped for the DAT1 3′ variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism. The children performed the Landmark Test, a well-validated measure yielding a spatial attentional asymmetry index (leftward to rightward attentional bias). Parents rated their child's response to MPH retrospectively using a three-point scale (no, mediocre or very good response). Additionally, parents used a symptom checklist to rate behavior while on and off medication. A within-family control design determined whether asymmetry indices predicted biased transmission of 10-repeat parental DAT1 alleles and/or response to MPH. It was found that left-sided inattention predicted transmission of the 10-repeat allele from parents to probands and was associated with the severity of ADHD symptomatology. Children rated as achieving a very good response to MPH displayed left-sided inattention, while those rated as achieving a poorer response did not. Our results suggest a subgroup of children with ADHD for whom the 10-repeat DAT1 allele is associated with left-sided inattention. MPH may be most efficacious in this group because it ameliorates a DAT1-mediated hypodopaminergic state.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a common childhood disruptive disorder affecting 3–6% of school-aged children worldwide, is characterized by age inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Family, twin, and adoption studies suggest that the disorder is heritable (see Kirley et al, 2002 for a review). Pharmacogenetic studies in ADHD suggest that individual differences in stimulant–response may be related to underlying genetic influences (Kirley et al, 2003; Hamarman et al, 2004). The 10-repeat allele of a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) situated in the 3′ untranslated region of the DAT1 gene (mapping to 5p15.3) has been associated with the clinical ADHD phenotype in a number of studies (Cook et al, 1995; Gill et al, 1997; Daly et al, 1999). This variant may confer an enhanced therapeutic response to methylphenidate (MPH) (Kirley et al, 2003; but see Winsberg and Comings, 1999; Roman et al, 2002). Here, we ask whether an attentional phenotype is related to (a) genetic variation in the DAT1 VNTR and (b) the therapeutic efficacy of MPH in ADHD.

Several lines of converging evidence underscore the relevance of the dopamine transporter gene to ADHD. First, MPH is known to inhibit the dopamine transporter (Volkow et al, 1998). The dopamine transporter is highly expressed in the human striatum where it serves as the primary means of dopamine reuptake (Garris and Wightman, 1994). Second, studies of both structural and functional imaging in ADHD have consistently implicated dopamine-rich frontostriatal circuits, particularly on the right, in the pathophysiology of ADHD (Casey et al, 1997; Vaidya et al, 1998; Teicher et al, 2000). These abnormalities are ameliorated by treatment with MPH (Vaidya et al, 1998; Teicher et al, 2000). Third, in vivo measurement of DAT with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has demonstrated elevated striatal transporter densities in adults (Dougherty et al, 1999; Dresel et al, 2000) and children (Cheon et al, 2003) with ADHD, compared to controls. In adults, treatment with MPH reduces transporter densities to near-normal levels (Dresel et al, 2000; Krause et al, 2000). Additionally, there is also evidence that children and adults who are homozygous for the 10-repeat DAT1 may have higher availability of DAT protein in the striatum, relative to those with the 9-repeat/10-repeat genotype (Heinz et al, 2000; Cheon et al, 2005).

These lines of evidence have led to a biological hypothesis of ADHD under which the 10-repeat DAT1 allele is thought to be associated with a greater abundance of DAT protein, resulting in a relative hypodopaminergia, perhaps particularly within the striatum (Kirley et al, 2002). According to this hypothesis, treatment with MPH may be most efficacious in 10-repeat homozygotes because it normalizes DAT density (Heinz et al, 2000; Kirley et al, 2003). There have, however, been a number of studies that have reported a poorer response to MPH in 10-repeat homozygotes, albeit often in relatively small samples (Rohde et al, 2003; Cheon et al, 2005).

Recent studies of susceptibility genes for psychiatric disorders have emphasized the utility of quantitative indices for assessing disease risk, termed endophenotypes. Endophenotypes are traits that more accurately predict dysfunction in discrete neural systems than conventional clinical phenotypes (Castellanos and Tannock, 2002). A small number of studies have examined whether genetic variants that are thought to confer susceptibility to ADHD are also associated with cognitive impairment (Swanson et al, 2000; Manor et al, 2002; Loo et al, 2003; Langley et al, 2004; Bellgrove et al, 2005, in press). The approach of linking a genetic risk factor with a cognitive phenotype has considerable heuristic value. Rather than seeking associations between a gene and a rudimentary diagnostic category, this approach measures the association between a gene and a strictly operationalized and objectively measured cognitive process.

In this context, we sought to determine whether the phenomenon of left-sided inattention in ADHD might be related to underlying DAT1 genotype and the therapeutic response to MPH. Left-sided inattention presents as a spatial bias of attention away from the left side. Left-sided inattention arises from dysfunction in any one of a number of right hemisphere cortical (prefrontal, parietal) and subcortical (striatal, thalamic) components of a distributed neural network for spatial attention (Mesulam, 1981). Dysfunction of the right hemisphere network results in more severe and long-lasting spatial inattention than equivalent left hemisphere dysfunction because of the dominance of the right hemisphere for the control of spatial attention: while right hemisphere networks allocate attention to both left and right hemispaces, left hemisphere networks do so only for the right hemispace (Mesulam, 1981). Consistent with animal studies that have reported neglect consequent upon lesions of the ascending dopaminergic pathways (Iversen, 1984), treatment with dopamine agonists reduces the extent of neglect in human subjects (Fleet et al, 1987).

A number of studies have reported the presence of attentional asymmetries in ADHD using both clinical and experimental measures of attention (Voeller and Heilman, 1988; Carter et al, 1995; Nigg et al, 1997; McDonald et al, 1999; Sheppard et al, 1999). Failure to replicate these effects in some studies (Wood et al, 1999; Klimkeit et al, 2003), nevertheless, suggests neuropsychological heterogeneity. Left-sided inattention has also been reported in the biological mothers of children with ADHD (Nigg et al, 1997), reinforcing its candidacy as an endophenotype. Critically, there is evidence for normalization of left-sided inattention in ADHD with MPH (Nigg et al, 1997; Sheppard et al, 1999).

This study addressed two distinct but related questions. First, using a family-based genetic association design, we asked whether a continuous measure of spatial attentional asymmetry was associated with DAT1 genotype. Specifically, we first hypothesized that left-sided inattention would be associated with the 10-repeat DAT1 allele in ADHD. Second, we asked whether the same continuous measure of attentional asymmetry was associated with retrospective ratings of the therapeutic response achieved by MPH. We hypothesized that if left-sided inattention may serve as a behavioral assay for a hypodopaminergic state in ADHD, then its existence may relate to the therapeutic response conferred by MPH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 43 right-handed ADHD participants were recruited as part of our ongoing genetic association studies and in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Trinity College Dublin and St James' Hospital, Dublin. DSM-IV diagnoses were confirmed using established diagnostic protocols. From our previously described cohort, ADHD probands (aged 6–16 years) were offered participation in the current study. The current sample is therefore not independent of our previously described cohort (Kirley et al, 2002, 2003). We have also recently described the neuropsychological performance, in relation to DAT1 genotype, including a distinct measure of attentional asymmetry, in a smaller subset (n=22) of the current cohort (Bellgrove et al, in press). Importantly, the current study extends the phenotypic description of our Irish sample using a different measure of attentional asymmetry, a within-family control design and ratings of MPH response. Replication with independent samples will, nevertheless, be required. Exclusion criteria included known neurological conditions including pervasive developmental disorders and epilepsy. Since reading disorder has been associated with attentional asymmetries (Facoetti et al, 2001), participants scoring more than 1½ standard deviations below the mean of the reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT-3) were also excluded (Table 1). Stimulant medication was withdrawn at least 24 h prior to the neuropsychological testing.

Predicting Methylphenidate Response

A total of 36 of these children were currently receiving or had in the past received treatment with MPH. Ratings of MPH response were obtained from parents in two ways: first, parents were asked to rate the therapeutic response achieved with MPH on a three-point scale from ‘no response’ to ‘mediocre’ to ‘very good’. Second, parents completed the Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Long Version (CPRS-R:L) (Conners, 1998) twice, retrospectively rating their child's symptoms while ‘on’ and ‘off’ MPH. We have previously reported an association between the 10-repeat allele of the DAT1 VNTR and the therapeutic response to MPH using this rating system (Kirley et al, 2003).

Testing Attentional Asymmetry: The Landmark Task

In this well-validated and brief (5 min) test, participants judge which end of a pre-bisected line looks shorter to them (Figure 1). Participants performed 20 trials of the Landmark Task. On 10 of these trials, the bisecting line was offset (either to the right or left) allowing accuracy of judgements to be determined. On the remaining 10 trials, the horizontal line was bisected in the middle.

The Landmark Task. (a) In the Landmark Task, participants are presented with a pre-bisected line and asked which end of the line is the shorter. Healthy participants tend to show a slight bias of attention to the left owing to the dominance of the right hemisphere for spatial judgements. This scenario leads to a relative inattention to the rightward extent of the line. (b) In patients with right hemisphere lesions and left spatial inattention, there is a bias of attention to the right that arises when the dominant attentional orienting bias of the right hemisphere has been weakened. This scenario leads to a relative inattention to the leftward extent of the line (shaded area) and the subjective experience of the left end of the line as the shorter. Trials on which the left end of the line was nominated as the shorter were designated ‘right-biased’. Trials on which the right end of the line was nominated as the shorter were designated ‘left-biased’. A continuous measure of spatial bias—the spatial Asymmetry Index—was calculated as (Nright-biased trials−Nleft-biased trials)/20. This yielded values ranging from –1 (leftward spatial bias/right spatial inattention) to +1 (rightward spatial bias/left spatial inattention).

DAT1 Genotyping

DNA was extracted from blood samples or buccal cells using the standard phenol–chloroform procedure from both parents and the ADHD proband in each family. Primer sequence and amplification conditions can be found elsewhere (Kirley et al, 2002). Two investigators, who were blind to the identity of the sample, independently scored all genotypes.

Statistical Analyses

Testing the association between DAT1 genotype and attentional asymmetry

In vitro studies indicate that the 10-repeat allele of the DAT1 VNTR may increase DAT expression (see Asherson, 2004 for review). For example, Fuke et al (2001) showed that the 10-repeat allele, relative to the 7- or 9-repeat alleles, increased gene expression using a reporter system. Mill et al (2002) also reported that mRNA levels in human brain and lymphocyte tissue varied with DAT1 VNTR, being higher in individuals with the 10- vs 9-repeat allele. Based on this evidence of differential gene expression as a function of VNTR alleles and the low frequency of individuals homozygous for the non-10-repeat alleles (less than 5% in the current sample), we compared the Landmark Asymmetry Indices of those ADHD probands without the 10-repeat DAT1 allele and those in possession of one copy of this allele (designated as Low-Risk DAT1) (n=21) to those in possession of two copies of this allele (designated as High-Risk DAT1) (n=22). Preliminary analyses revealed that performance measures were normally distributed and therefore parametric tests were used in statistical comparisons.

Using a family-based design and a logistic regression adaptation of the transmission disequilibrium test (LR-TDT) (Waldman et al, 1999), we also used parental genotype information to examine whether the Landmark Asymmetry Index predicted biased transmission of high-risk (10-repeat), vs low-risk (other alleles), parental DAT1 alleles to ADHD probands. This method is robust against any population stratification effects.

Testing the association between attentional asymmetry and response to MPH

Firstly, Landmark Asymmetry Indices were compared as a function of Medication Response Group (None or Mediocre vs Very Good) using a univariate ANOVA. Secondly, Landmark Asymmetry Indices were compared as a function of the combination of Medication Response Group and DAT1 Genotype (Low-Risk DAT1 vs High-Risk DAT1).

RESULTS

Testing the Association between DAT1 Genotype and Attentional Asymmetry

When symptomatology was measured dimensionally, significant differences emerged between the Low- and High-Risk DAT1 ADHD groups in both DSM-IV Inattentive and Total age-related normative scores (t-scores), as measured by the CPRS-R:L (Table 1). Further, Landmark Asymmetry Indices correlated positively with continuous measures of DSM-IV Inattentiveness (r(41)=0.35, p=0.02) and DSM-IV Total symptom scores (r(41)=0.40, p=0.01) but not DSM-IV Hyperactivity/Impulsiveness (r(41)=0.29, p=0.065). The direction of these correlations suggests that greater symptom severity, particularly with respect to inattentive symptoms, is associated with left-sided inattention.

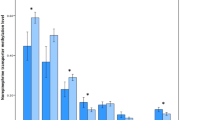

There was a significant effect of DAT1 Genotype Group on the Asymmetry Index (F(1,41)=10.9, p=0.002; r2=0.19) that was driven by the right spatial bias/left-sided inattention of the High-Risk DAT1 ADHD group (M=+0.09, SD=0.29), in comparison to the left spatial bias/right-sided inattention of the Low-Risk DAT1 ADHD (M=−0.17, SD=0.23) (Figure 2). Despite the small number of participants not in possession of a 10-repeat DAT1 allele (n=2), regression revealed a parametric effect of increasing number of 10-repeat DAT1 alleles (0, 1, or 2) on Landmark Asymmetry Indices ((F(1,41)=12.23, p=0.001; r2=0.21) (see Table 2). This result suggests an additive effect of possession of the 10-repeat allele.

Mean Landmark Asymmetry Indices as a function of ADHD DAT1 Genotype Group. The performance accuracy of the groups on the Landmark task was firstly compared using those trials on which the midpoint of the line was offset. Accuracy was high across both groups (mean accuracies >73%) and not significantly different between the ADHD DAT1 Genotype Groups (F(1,41)=0.57, p=0.45).

A logistic regression model was used to examine whether the Landmark Asymmetry Index predicted preferential transmission of high-risk (10-repeat), vs low-risk (other alleles), parental DAT1 alleles. The coding of transmitted alleles from heterozygous parents resulted in 40 informative transmissions. The Landmark Asymmetry Index significantly predicted biased transmission of high-risk, vs low-risk, parental DAT1 alleles (χ2(df=1)=7.43, p=0.006, 37% variance explained). This association was stronger than when using DSM-IV Inattentive (χ2(df=1)=3.6, p=0.058), Hyperactive/Impulsive (χ2(df=1)=2.5, p=0.115), or Total Symptoms (χ2(df=1)=3.6, p=0.059) as continuous predictor variables. Thus, while left spatial inattention is related to dimensional measures of ADHD symptomatology, the former is more strongly associated with DAT1 genotype than the latter. This result satisfies a key assumption of the endophenotype approach.

Testing the Association between Attentional Asymmetry and Response to MPH

Retrospective ratings of MPH response using the three-point scale (No Response vs Mediocre Response vs Very Good Response) were available for 36 children and adolescents with ADHD. A total of 15 of these participants were rated as achieving No Response or a Mediocre Response, while 21 were rated as achieving a Very Good Response. There was a significant difference in the Landmark Asymmetry Index as a function of Medication Response Group (F(1,34)=5.22, p=0.03, r2=0.11), which was driven by the right spatial bias/left-sided inattention of the Very Good Response group (M=+0.05, SD=0.29), in comparison to the left spatial bias/right-sided inattention of the No/Mediocre Response group (M=−0.15, SD=0.19).

Given the a priori prediction that those children achieving a very good response to MPH and possessing two ‘high-risk’ 10-repeat DAT1 alleles would show left-sided inattention (right bias) on the Landmark Task, we compared the performance of this group (High-Risk DAT1/Very Good Response) (n=12) to the three other Genotype/Medication Response groupings (see Figure 3).

There was a significant effect of DAT1 Genotype/Medication Response Group on the Landmark Asymmetry Index (F(3,32)=4.12, p=0.01, r2=0.21) (Figure 3). Figure 3 indicates that Asymmetry Indices became increasingly right biased as a function of DAT1 Genotype/Medication Response Group. As hypothesized, the High-Risk DAT1/Very Good Response group were the only group to display left-sided inattention (M=+0.13, SD=0.32), with the Low-Risk DAT1/Mediocre Response Group showing a leftward bias (M=−0.25, SD=0.11). Both the Low-Risk DAT1/Very Good Response (M=−0.07, SD=0.21) and High-Risk DAT1/Mediocre Response (M=−04, SD=0.21) groupings had small leftward biases. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections revealed that the Asymmetry Indices of the High-Risk DAT1/Very Good Response Group and the Low-Risk DAT1/Mediocre Response Group were significantly different (p<0.01). No other pairwise comparisons were significant.

Changes in symptom severity when on and off MPH, as rated retrospectively by parents using the CPRS-R:L, were available for 32 ADHD participants. The High-Risk DAT1 ADHD group achieved greater symptom reduction than the Low-Risk DAT1 ADHD group in terms of both DSM-IV Hyperactive/Impulsive (F(1,30)=5.289, p=0.03, r2=0.12) and DSM-IV Total symptoms (F(1,30)=4.40, p=0.04, r2=0.13) but not DSM-IV Inattentive symptoms (F(1,30)=1.99, p=0.169, r2=0.06).

DISCUSSION

This study reports that left-sided inattention is related to clinical ADHD symptomatology, the 10-repeat DAT1 allele, and the therapeutic response to MPH. 10-repeat DAT1 homozygotes displayed left-sided inattention, whereas those possessing one or no copies of this allele did not. This result extends preliminary reports of an effect of DAT1 genotype on neuropsychological performance in ADHD (Loo et al, 2003; Bellgrove et al, in press). Importantly, using a within-family control design, we report that scores on the Landmark Asymmetry Index predict biased transmission of the 10-repeat DAT1 allele from parents to probands. The greater effect of the 10-repeat allele on attentional asymmetry observed in homozygotes, vs heterozygotes, suggests additive rather than dominance effects of the 10-repeat allele. As we hypothesized, left-sided inattention was associated with an enhanced therapeutic response to MPH, irrespective of DAT1 status, but was most pronounced in 10-repeat DAT1 homozygotes who achieved a very good response to MPH. Our data support the existence of a subgroup of ADHD that is linked to the 10-repeat allele of the DAT1 VNTR, and is defined (a) in symptom terms, by higher levels of inattentive and total symptomatology (but see Waldman et al, 1998); (b) in neuropsychological terms, by left-sided inattention, and perhaps also poor sustained attention (Loo et al, 2003); and (c) in pharmacogenetic terms, by an enhanced response to MPH (Kirley et al, 2003).

Based on the data reported herein and the previously reviewed literature, we propose the following genetic–neurophysiological mechanism as part of the pathophysiology of ADHD. Increased transporter density (or activity) is associated with the 10-repeat DAT1 allele (or another genetic variant in linkage disequilibrium with the DAT1 VNTR) in ADHD (see Cheon et al, 2005). Overactive transporters reduce extracellular dopamine, perhaps particularly within right hemisphere attentional networks. The resultant hypoactivation within right hemisphere systems weakens the attentional bias of the right hemisphere, unmasking the attentional bias of the left hemisphere thus driving spatial attention in a rightward direction (Kinsbourne, 1993). Variation in the DAT1 gene may therefore confer susceptibility to ADHD, in part because of varying effects on the development of brain mechanisms modulating (spatial) attention.

Treatment with MPH may inhibit the transporter, restoring both dopaminergic balance and the reciprocal balance between spatial attentional systems. Accordingly, treatment with MPH may be most effective in those individuals with the greatest transporter densities or activities. Insofar as the Landmark Asymmetry Index is able to act as a behavioral assay for this neural mechanism, then those ADHD individuals presenting with left-sided inattention may be more likely to achieve an enhanced response to MPH. Our data also suggest that knowing the DAT1 genotype of an individual may strengthen this association.

The above model, however, assumes that the DAT1 VNTR modulates transporter densities asymmetrically in ADHD, thus giving rise to the left-sided inattention reported herein. While there is, as yet, little direct evidence for this assumption, a number of studies do suggest a cerebral asymmetry in transporter densities. For example, Laakso et al (2000) reported higher striatal dopamine transporter binding in healthy subjects within the right, relative to left, striatum. Cheon et al (2003) also reported that DAT binding ratios within the basal ganglia of children with ADHD, relative to controls, were elevated by 51% on the right and 40% on the left. Further, it has recently been demonstrated that the beneficial effect of MPH on attention and impulsivity in ADHD is related to a reduction in the availability of D2/D3 receptors. This reduction in receptor availability is indicative of a pharmacologically evoked increase in extracellular dopamine by blockade of the transporter that is maximal in the right striatum (Rosa-Neto et al, 2005). It should also be noted, however, that the results reported herein could also arise from an interaction between DAT1 genotype and its associated alteration in dopaminergic transmission, and structural and/or functional changes within right hemisphere attentional systems (eg Castellanos et al, 1994; Casey et al, 1997; Bush et al, 1999; Sowell et al, 2003) that are unrelated to DAT1 genotype.

There are several limitations of this study that require comment. First, the sample size is relatively small for a genetic association study. For example, only two probands possessed the 9/9 genotype. Nevertheless, our results are consistent across analyses focusing on possession and transmission of high-risk alleles. While the latter analysis (LR-TDT) sacrifices power by focusing on transmissions from heterozygous parents only, the results were highly significant and survive correction for multiple comparisons. DAT1 genotype accounted for 19% of the variance in the Landmark Asymmetry Index in the ANOVA-based analysis. This effect on spatial cognition is larger than is typically reported with functional variants, such as the COMT Val/Met polymorphism (Egan et al, 2001). Larger collaborative studies using a range of spatial attentional tasks are required to confirm and extend our results. Second, we assessed medication response using a simple nonvalidated three-point scale, and collected retrospective parental ratings. While these results should be viewed as preliminary until replicated within a prospective study, it should be noted that these ratings are unlikely to be biased with respect to DAT1 genotype. Third, we have proposed a biological hypothesis of the relation between left-sided inattention, DAT1 genotype, and MPH response in which dysfunction to attentional systems is centered on the right striatum. While this hypothesis is advanced based upon the known action of stimulants at transporters within the striatum, left-sided inattention can also arise from right parietal or prefrontal lesions (Robertson and Marshall, 1993). We cannot discount the possibility that our behavioral results reflect fronto-parietal dysfunction.

In summary, our results show that left-sided inattention in ADHD is related to both underlying DAT1 genotype and the therapeutic response conferred by MPH. Our results are internally consistent in demonstrating an attentional endophenotype that relates to ADHD symptomatology, DAT1 genotype, and the therapeutic efficacy of MPH. The further study of spatial (in)attention in ADHD, in relation to DAT1 genotype, may provide a window into the neurobiology of ADHD.

References

Asherson P (2004). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the post-genomic era. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13 (Suppl 1): 150–170.

Bellgrove MA, Domschke K, Hawi Z, Kirley A, Mullins C, Robertson IH et al (2005). The methionine allele of the COMT polymorphism impairs prefrontal cognition in children and adolescents with ADHD. Exp Brain Res 163: 352–360.

Bellgrove MA, Hawi Z, Kirley A, Gill M, Robertson IH (in press). Dissecting the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) phenotype: Sustained attention, response variability and spatial attentional asymmetries in relation to dopamine transporter (DAT1) genotype. Neuropsychologia.

Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA et al (1999). Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the Counting Stroop. Biol Psychiatry 45: 1542–1552.

Carter CS, Krener P, Chaderjian M, Northcutt C, Wolfe V (1995). Asymmetrical visual-spatial attentional performance in ADHD: evidence for a right hemispheric deficit. Biol Psychiatry 37: 789–797.

Casey BJ, Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Marsh WL, Hamburger SD, Schubert AB et al (1997). Implication of right frontostriatal circuitry in response inhibition and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36: 374–383.

Castellanos FX, Giedd JN, Eckburg P, Marsh WL, Vaituzis AC, Kaysen D et al (1994). Quantitative morphology of the caudate nucleus in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1791–1796.

Castellanos FX, Tannock R (2002). Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nat Rev Neurosci 3: 617–628.

Cheon KA, Ryu YH, Kim JW, Cho DY (2005). The homozygosity for 10-repeat allele at dopamine transporter gene and dopamine transporter density in Korean children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: relating to treatment response to methylphenidate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 95–101.

Cheon KA, Ryu YH, Kim YK, Namkoong K, Kim CH, Lee JD (2003). Dopamine transporter density in the basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30: 306–311.

Conners CK (1998). Rating scales in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: use in assessment and treatment monitoring. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 24–30.

Cook EH, Stein MA, Krasowski MD, Cox NJ, Olkon DM, Kieffer JE et al (1995). Association of attention-deficit disorder and the dopamine transporter gene. Am J Hum Genet 56: 993–998.

Daly G, Hawi Z, Fitzgerald M, Gill M (1999). Mapping susceptibility loci in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: preferential transmission of parental alleles at DAT1, DBH and DRD5 to affected children. Mol Psychiatry 4: 192–196.

Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, Fischman AJ (1999). Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 354: 2132–2133.

Dresel S, Krause J, Krause KH, LaFougere C, Brinkbaumer K, Kung HF et al (2000). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: binding of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 to the dopamine transporter before and after methylphenidate treatment. Eur J Nucl Med 27: 1518–1524.

Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Callicott JH, Mazzanti CM, Straub RE et al (2001). Effect of COMT Val 108/158 Met genotype on frontal lobe function and risk for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6917–6922.

Facoetti A, Turatto M, Lorusso ML, Mascetti GG (2001). Orienting of visual attention in dyslexia: evidence for asymmetric hemispheric control of attention. Exp Brain Res 138: 46–53.

Fleet WS, Valenstein E, Watson RT, Heilman KM (1987). Dopamine agonist therapy for neglect in humans. Neurology 37: 1765–1770.

Fuke S, Suo S, Takahashi N, Koike H, Sasagawa N, Ishiura S (2001). The VNTR polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene affects gene expression. Pharmacogenomics J 1: 152–156.

Garris PA, Wightman RM (1994). Different kinetics govern dopaminergic transmission in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and striatum: an in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci 14: 442–450.

Gill M, Daly G, Heron S, Hawi Z, Fitzgerald M (1997). Confirmation of association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and a dopamine transporter polymorphism. Mol Psychiatry 2: 311–313.

Hamarman S, Fossella J, Ulger C, Brimacombe M, Dermody J (2004). Dopamine receptor 4 (Drd4) 7-repeat allele predicts methylphenidate dose response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a pharmacogenetic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 14: 564–574.

Heinz A, Goldman D, Jones DW, Palmour R, Hommer D, Gorey JG et al (2000). Genotype influences in vivo dopamine transporter availability in human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 133–139.

Iversen SD (1984). Behavioural effects of manipulation of basal ganglia neurotransmitters. Ciba Found Symp 107: 183–200.

Kinsbourne M (1993). Orientational bias model of unilateral neglect: evidence from attentional gradients within hemispace. In: Robertson IH, Marshall JC (eds). Unilateral Neglect: Clinical and Experimental Studies. Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale. pp 63–86.

Kirley A, Hawi Z, Daly G, McCarron M, Mullins C, Millar N et al (2002). Dopaminergic system genes in ADHD: toward a biological hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 27: 607–619.

Kirley A, Lowe N, Hawi Z, Mullins C, Daly G, Waldman I et al (2003). Association of the 480 bp DAT1 allele with methylphenidate response in a sample of Irish children with ADHD. Am J Med Genet 121B: 50–54.

Klimkeit EI, Mattingley JB, Sheppard DM, Lee P, Bradshaw JL (2003). Perceptual asymmetries in normal children and children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Brain Cognition 52: 205–215.

Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K (2000). Increased striatal dopamine transporter in adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of methylphenidate as measures by single photon emission computed tomography. Neurosci Lett 285: 107–110.

Laakso A, Vilkman H, Alakare B, Haaparanta M, Bergman J, Solin O et al (2000). Striatal dopamine transporter binding in neuroleptic-naive patients with schizophrenia studied with positron emission tomography. Am J Psychiatry 157: 269–271.

Langley K, Marshall L, Van Den Bree M, Thomas H, Owen M, O'Donovan M et al (2004). Association of the dopamine d(4) receptor gene 7-repeat allele with neuropsychological test performance of children with ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 161: 133–138.

Loo SK, Specter E, Smolen A, Hopfer C, Teale PD, Reite ML (2003). Functional effects of the DAT1 polymorphism on EEG measures in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42: 986–993.

Manor I, Tyano S, Eisenberg J, Bachner-Melman R, Kotler M, Ebstein RP (2002). The short DRD4 repeats confer risk to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a family-based design and impair performance on a continuous performance test (TOVA). Mol Psychiatry 7: 790–794.

McDonald S, Bennett KM, Chambers H, Castiello U (1999). Covert orienting and focusing of attention in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychologia 37: 345–356.

Mesulam M-M (1981). A cortical network for directed attention and unilateral neglect. Ann Neurol 10: 309–325.

Mill J, Asherson P, Browes C, D'Souza U, Craig I (2002). Expression of the dopamine transporter gene is regulated by the 3′ UTR VNTR: evidence from brain and lymphocytes using quantitative RT-PCR. Am J Med Genet 114B: 975–979.

Nigg JT, Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP (1997). Covert visual spatial attention in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: lateral effects, methylphenidate response, and results for parents. Neuropsychologia 35: 165–176.

Robertson IH, Marshall JC (eds) (1993). Unilateral Neglect: Clinical and Experimental Studies. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates: Hillsdale, NJ.

Rohde LA, Roman T, Szobot C, Cunha RD, Hutz MH, Biederman J (2003). Dopamine transporter gene, response to methylphenidate and cerebral blood flow in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot study. Synapse 48: 87–89.

Roman T, Szobot C, Martins S, Biederman J, Rohde LA, Hutz MH (2002). Dopamine transporter gene and response to methlphenidate in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacogenetics 12: 497–499.

Rosa-Neto P, Lou HC, Cumming P, Pryds O, Karrebaek H, Lunding J et al (2005). Methylphenidate-evoked changes in striatal dopamine correlate with inattention and impulsivity in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage 25: 868–876.

Sheppard DM, Bradshaw JL, Mattingley JB, Lee P (1999). Effects of stimulant medication on the lateralisation of line bisection judgements of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 66: 57–63.

Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW, Peterson BS (2003). Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 362: 1699–1707.

Swanson J, Oosterlaan J, Murias M, Schuck S, Flodman P, Spence MA et al (2000). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder children with a 7-repeat allele of the dopamine receptor D4 gene have extreme behavior but normal performance on critical neuropsychological tests of attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4754–4759.

Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Polcari A, Glod CA, Maas LC, Renshaw PF (2000). Functional deficits in basal ganglia of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder shown with functional magnetic resonance imaging relaxometry. Nat Med 6: 470–473.

Vaidya CJ, Austin G, Kirkorian G, Ridlehuber HW, Desmond JE, Glover GH et al (1998). Selective effects of methylphenidate in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a functional magnetic resonance study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14494–14499.

Voeller KK, Heilman KM (1988). Attention deficit disorder in children: a neglect syndrome? Neurology 38: 806–808.

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Gatley SJ, Logan J, Ding YS et al (1998). Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry 155: 1325–1331.

Waldman ID, Robinson BF, Rowe DC (1999). A logistic regression based extension of the TDT for continuous and categorical traits. Ann Hum Genet 63 (Part 4): 329–340.

Waldman ID, Rowe DC, Abramowitz A, Kozel ST, Mohr JH, Sherman SL et al (1998). Association and linkage of the dopamine transporter gene and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: heterogeneity owing to diagnostic subtype and severity. Am J Hum Genet 63: 1767–1776.

Winsberg BG, Comings DE (1999). Association of the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) with poor methylphenidate response. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38: 1474–1477.

Wood C, Maruff P, Levy F, Farrow M, Hay D (1999). Covert orienting of visual spatial attention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: does comorbidity make a difference. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 14: 179–189.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Irish Health Research Board to M Gill and IH Robertson. We thank Redmond O'Connell and Veronika Dobler. Drs Bellgrove, Gill, and Robertson have filed a preliminary short-term application with the Irish Patent Office, application number S2004/0236, dealing with ‘Predicting Methylphenidate Response in ADHD’. The Assignee is the Provost, Fellows, and Scholars of the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin. This application is based strongly on the data presented in the manuscript under consideration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bellgrove, M., Hawi, Z., Kirley, A. et al. Association between Dopamine Transporter (DAT1) Genotype, Left-Sided Inattention, and an Enhanced Response to Methylphenidate in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol 30, 2290–2297 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300839

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300839

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Reduced fine motor competence in children with ADHD is associated with atypical microstructural organization within the superior longitudinal fasciculus

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2021)

-

DNA methylation of dopamine-related gene promoters is associated with line bisection deviation in healthy adults

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Association of night-waking and inattention/hyperactivity symptoms trajectories in preschool-aged children

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Developmental brain trajectories in children with ADHD and controls: a longitudinal neuroimaging study

BMC Psychiatry (2016)

-

The NEIL Memory Research Unit: psychosocial, biological, physiological and lifestyle factors associated with healthy ageing: study protocol

BMC Psychology (2015)